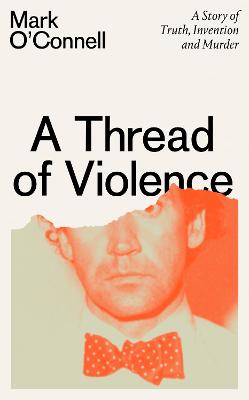

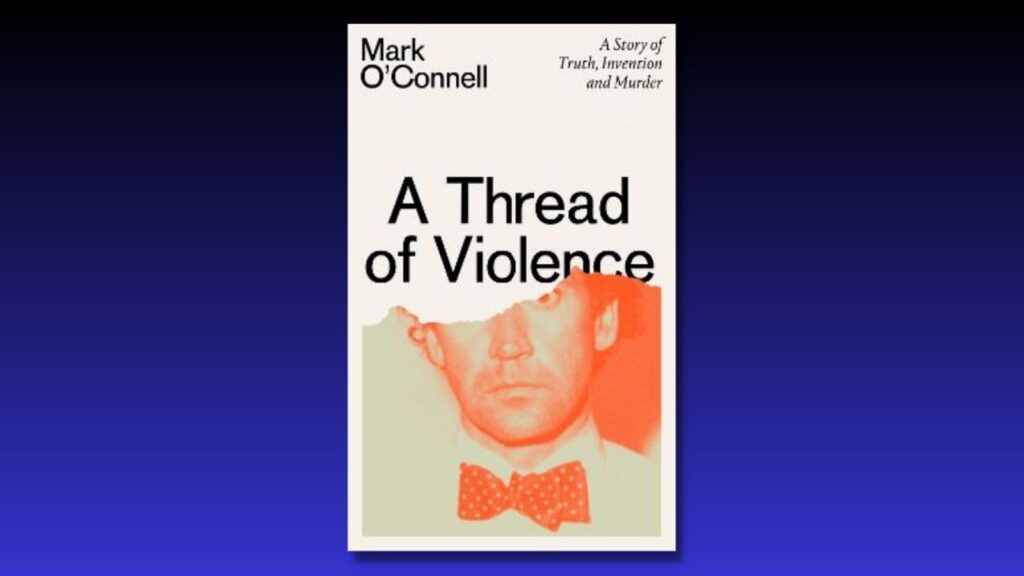

A Thread of Violence: A Story of Truth, Invention, and Murder|Mark O’Connell| Granta|£16.99| ISBN:9781783787708

A cross between a murder mystery and an academic treatise—A Thread of Violence

by John Kirkaldy

In July 1982, Malcolm Macarthur, the wealthy heir to a small estate, battered nurse Bridie Gargan with a sledge hammer, while she was sunbathing in Phoenix Park. A few days later, he shot farmer Donal Dunne at close range, in Edenderry, County Offaly.

The case is one of the most sensational in Irish history and was a step towards the downfall of the Government of Charles Haughey.

Macarthur was subsequently arrested in the most bizarre circumstances in the home of the Government’s Chief Law Officer, Attorney General, Patrick Connolly, where he was staying as a guest, and on occasions being driven in a government chauffeured car. The case is one of the most sensational in Irish history and was a step towards the downfall of the Government of Charles Haughey.

The book is much more than a meticulous account of the two murders and Macarthur’s trial. It is also a polemical essay which attempts to fathom the motivation of this unlikely killer, and a general examination of the urge to violence.

Deepening relationship

O’Connell became obsessed with Macarthur. His PhD was on John Banville, whose 1989 novel, The Book of Evidence, was based on these events. His grandparents had lived in the same block of flats as Connolly. “The sheer awfulness of what he had done seemed unfathomable, and yet I felt strongly that we might share a language in which he could speak to me of it. I became determined to try.”

“You know, you have become a very important part of my life,” commented Macarthur. “And vice versa,” replied O’Connell.

In 2012, Macarthur was released from prison, having served his full sentence. He was seen occasionally around Dublin, even attending an event featuring Banville. Finally, after much deliberation, O’Connell and subject met at a pedestrian crossing and had an hour-long chat. A deepening relationship soon developed over many meetings and phone calls. “You know, you have become a very important part of my life,” commented Macarthur. “And vice versa,” replied O’Connell.

This sometimes produced interesting ethical questions. Once, when putting his three-year old daughter to bed, O’Connell received a call from Macarthur. “All the rest of the evening, I couldn’t get it out of my head: his name on the screen, the unsettling thrum on the phone in her little hands.”

O’Connell produces a detailed account of Macarthur’s background. It is unusual but hardly suggests a vicious killer. Many observers felt that he was Anglo-Irish and had an academic background. In fact, the family was originally from Scotland and were Catholics. He was a dilettante, who delighted in days spent in libraries in Dublin, especially Trinity, Cambridge and California, but he never held any academic post. He relished discussion, often at Bartley’s, a well-known Dublin bar.

O’Connell produces a detailed account of Macarthur’s background. It is unusual but hardly suggests a vicious killer.

Macarthur’s persona was one of confident assurance; he was good company and elegantly dressed. His parents had been divorced and there may have been some domestic violence. They seemed to take little interest in him, allowing a great degree of freedom.

Motive for murder

The motivation for the murders is obvious: money. Macarthur never had a proper paying job and he simply lived off his inheritance from the estate of IR£70,000 (€900,000 in today’s prices). He liked a comfortable life style and claimed that he was a soft touch for friends, some of whom did not pay him back. In addition, he formed a relationship with Brenda Little, and in October 1975, they had a child (they never married).

Robberies were in the news, thanks to the IRA, and Macarthur decided that this was the way forward.

It was through Little that Macarthur was able to stay with Connolly after the murders; she was an old friend. In May 1982, the couple travelled to the Canaries; shortly afterwards, Macarthur announced that he needed to go to Ireland for business reasons but would return. He had run out of money.

Robberies were in the news, thanks to the IRA, and Macarthur decided that this was the way forward. All he needed was a shot gun (he had seen one advertised in Edenderry), and some transport to get there and back. A sledge hammer would be a good persuader.

All of this is well-known history and has often been repeated, especially in the 40th anniversary year of the trial, in articles, books and podcasts. O’Connell’s book, written in a detached, academic style, however, brings an additional dimension. As his relationship with Macarthur deepens, so our understanding of the emotional and psychological forces involved becomes more focussed, albeit never perfectly.

Theories and explanations

Three questions seem to underline the book. How did an obviously intelligent man produce such an incompetent plan with so little chance of success? How did he cope over the years with the horror of killing two people in such an appalling fashion? Did the growing relationship between the author and murderer reduce the quest for honesty? O’Connell does not produce definitive answers to these questions but he does provide some fresh insights to the case.

He often referred to the murders as ‘a criminal episode,’ as if it were something out of the ordinary. He made much of the fact that he had lived a blameless life before and after the murders

The book suggests some theories and explanations but they are often somewhat contradictory. One of the detectives, who interviewed Macarthur, claimed that he was ‘a Walter Mitty type.’ O’Connell believes that there was a class motive: ‘an element of narcissistic rage…a blind fury at the collapse of a protective façade.’ He also felt that Macarthur was not only able on occasions to invent lies, but to believe them.

But there were also other ways of avoiding reality. He often referred to the murders as ‘a criminal episode,’ as if it were something out of the ordinary. He made much of the fact that he had lived a blameless life before and after the murders (he was a model prisoner). O’Connell examines the notion of automatonism, a way of detaching the murderer from his actions.

Macarthur was obsessed in symbolically wrapping the weapons and much of the furniture in his flat in bin liners to keep them clean. This also links to theories of cognitive dissonance, a way of mentally twisting reality to suit personal needs. In a bizarre way, Macarthur placed some of the blame for what happened on his victims. Gargan’s fate was settled, he claimed, when she began to struggle and did not accept his demands.

O’Connell often wanted to know did Macarthur feel any remorse for his actions. “Yes, he did feel remorse, a great and terrible remorse, but that he had never allowed it to overwhelm him, to become the defining fact of his life.”

O’Connell seems aware of getting too close to his subject. But increasingly, he identifies to an extent with Macarthur’s educational background, and his enjoyment of academic freedom as a motive for his actions, but not as a justification: “One of the things I feel is a queasy, perverse sympathy—not for what he did, of course, but for the terror at the loss of privilege that led him to it.” As somebody who has also enjoyed such privileges, I too can to an extent understand such feelings (offset by the fact that I married a farmer’s daughter from Edenderry!).

This book is a very successful cross between a murder mystery and an academic treatise. Haughey was not always the most truthful of politicians but he got it right, although it needed Conor Cruise O’Brien to devise the acronym. It was Grotesque. Unbelievable. Bizarre. Unprecedented.

John Kirkaldy has a PhD in Irish History, worked for many years with the Open University and has been reviewing for Books Ireland since 1980. He has contributed to three Irish history anthologies, a school textbook, and has been involved in a number of Open University History documentary series. Aged 70, two years ago, he went round the world on a much delayed gap year described in his book, I’ve Got a Metal Knee: a 70-Year Old’s Gap Year.