Experience an extract from Nets of Wonder in words, art, and music

Nets of Wonder is a creative cross-pollination of writing, visual art, and music. There are twelve reflections in the book, each divided into seasons, with every written piece having its response in art and music.

Words are from clinical psychologist and contributor to Sunday Miscellany Olive Travers, with pen and ink artwork from Donegal artist Barry Britton, and music from composer and multi-instrumentalist Eamon Travers.

It’s up to the reader/viewer/listener as to how to approach and absorb the book, whether by focusing on one piece or one medium at a time, or by listening, looking, and reading simultaneously to experience the book holistically.

Below in words, art, and music, is an extract from Nets of Wonder, “For Fear of Little Men”.

For Fear of Little Men, by Olive Travers

Up the airy mountain,

Down the rushy glen,

We daren’t go a-hunting,

For fear of little men;

Wee folk, good folk,

Trooping all together;

Green jacket, red cap,

And white owl’s feather.

There are few who do not know by heart, from school days, this first verse of ‘The Fairies’ by William Allingham; however, I have difficulty understanding why it is such a beloved poem. Perhaps few go on to learn all six stanzas with their unfolding macabre story of these little men or perhaps readers are lulled by the light, tripping metre of the poem, which is so at odds with the doings of these little men.

Some, though, have heard the darkness underneath. The opening lines have been used in settings as diverse as the 1973 horror film Don’t Look in the Basement, 1971’s Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, and ‘For Fear of Little Men’ was the working title of Terry Pratchett’s second young adult Discworld novel, which became The Wee Free Men.

Even as a child growing up near Ballyshannon, the town from which the poet hails, the poem filled me with a nameless dread, rather than the excited terror that attracts children to the macabre. These were not the gauzy winged, wand-waving fairies from the stories I loved. They were malign, sinister creatures, which not only hunted in gangs, and press-ganged frogs into their evil service, but who also lurked both by the sea and inland.

Down along the rocky shore

Some make their home,

They live on crispy pancakes

Of yellow tide-foam;

Some in the reeds

Of the black mountain-lake,

With frogs for their watch-dogs,

All night awake.

What was really disturbing also was the message that no one, not even their king, could control them.

High on the hill-top

The old King sits;

He is now so old and grey

He’s nigh lost his wits.

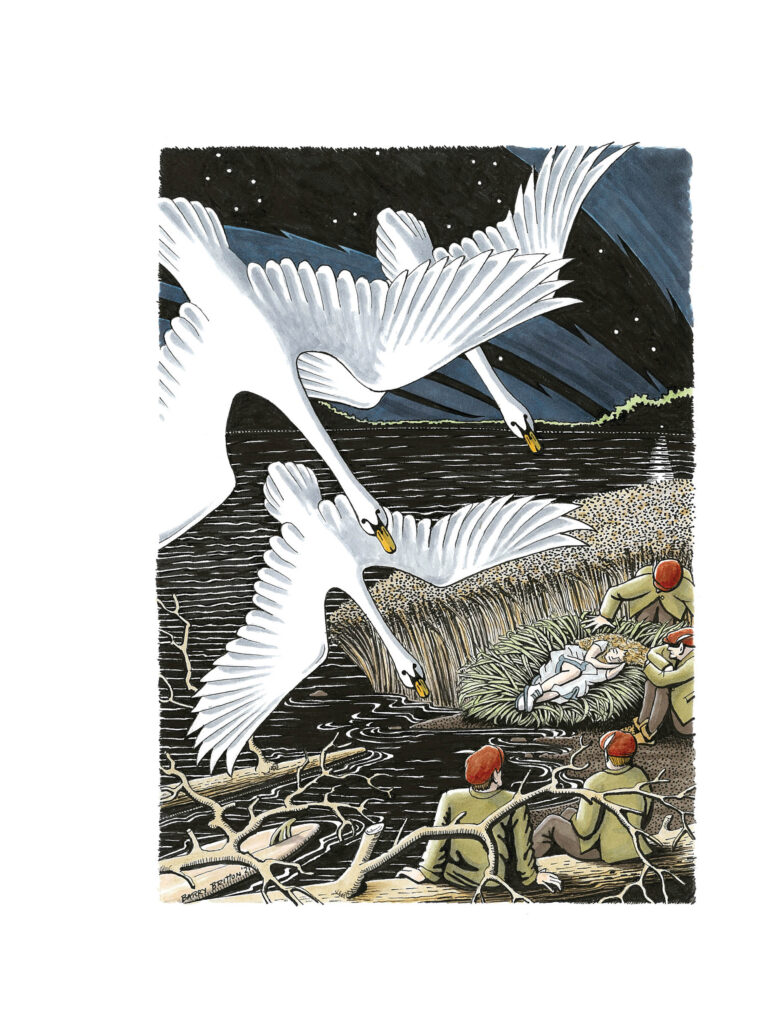

But it is the fourth stanza, in which little Bridget is stolen, that makes me wonder if there is something in the dark imagination of the poet that foreshadows real-life events, or is it just that when darkness is visited on real life I feel again that frisson of fear I felt when I heard the poem as a child?

They stole little Bridget

For seven years long;

When she came down again

Her friends were all gone.

They took her lightly back

Between the night and morrow;

They thought she was fast asleep,

But she was dead with sorrow.

They have kept her ever since

Deep within the lake,

On a bed of flag-leaves,

Watching till she wake.

Of course, Allingham was drawing on much older stories from Celtic folklore of fairies and changelings, and another poet from the same area, W.B. Yeats, born forty years after Allingham, echoed this same theme in ‘The Stolen Child’.

Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand.

Still, the fate of little Bridget seems too close to the bone, with its dark undertones seeming to be a precursor to real-life tragedies with which we are all too familiar.

The capriciousness of the fairies is evident in the next stanza, in which there is a sudden descent from the tragedy of the child dead with sorrow to the trivial spitefulness of their revenge on anyone who harms their trees.

By the craggy hill-side,

Through the mosses bare,

They have planted thorn-trees

For pleasure here and there.

Is any man so daring

As dig them up in spite,

He shall find their sharpest thorns

In his bed at night.

The poem ends with the repetition of the opening, superficially catchy lines, before those scary bogeymen trip off the page – none too soon in my opinion. Yet I cannot get away from Allingham and his fairies. From my window I look out on St Anne’s Church in Ballyshannon, in whose graveyard Allingham’s ashes were buried in 1889. It is high up overlooking the town on Mullaghnashee – Mullagh na Sídhe, also known as Sídhe Aodh Ruadh, the Fairy Mound of Red Hugh – where it is believed there is an access point to the middle world of the fairies.