by Ruth McKee

Looking at the very early photographs in Old Ireland in Colour you realise that every last person—every child, every infant looking out at the camera—is now a ghost.

The pictures begin in the late 1800s. By 1881, the introduction tells us, most counties in Ireland had at least one photographer; many of them were women. For the following decades, our history—the big and the small stories—were captured in black and white.

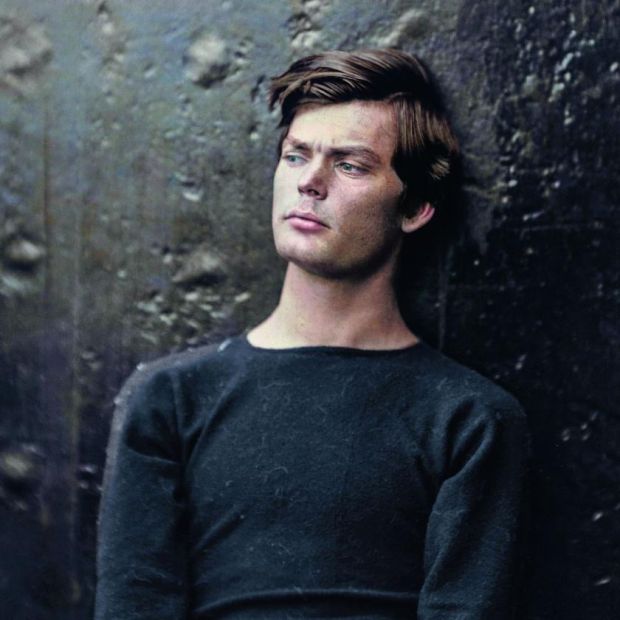

We’re familiar now with the colouring of black and white images from history, whether it’s the portrait of Chekov going from monochrome literary figure to handsome hipster in a breath, or Albert Eisenstaedt’s famous black and white photo of that kiss between nurse and sailor in Times Square on VJ Day August 14th, 1945—or the unsettling modernity of Lewis Payne, colourised by artist Marina Amaral in her exceptional book The World Aflame. Here, it is 1865, and we see Lewis, the ex-Confederate (who conspired with John Wilkes Booth to assassinate Abraham Lincoln) looking for all the world like he has walked off a photo-shoot for Zara.

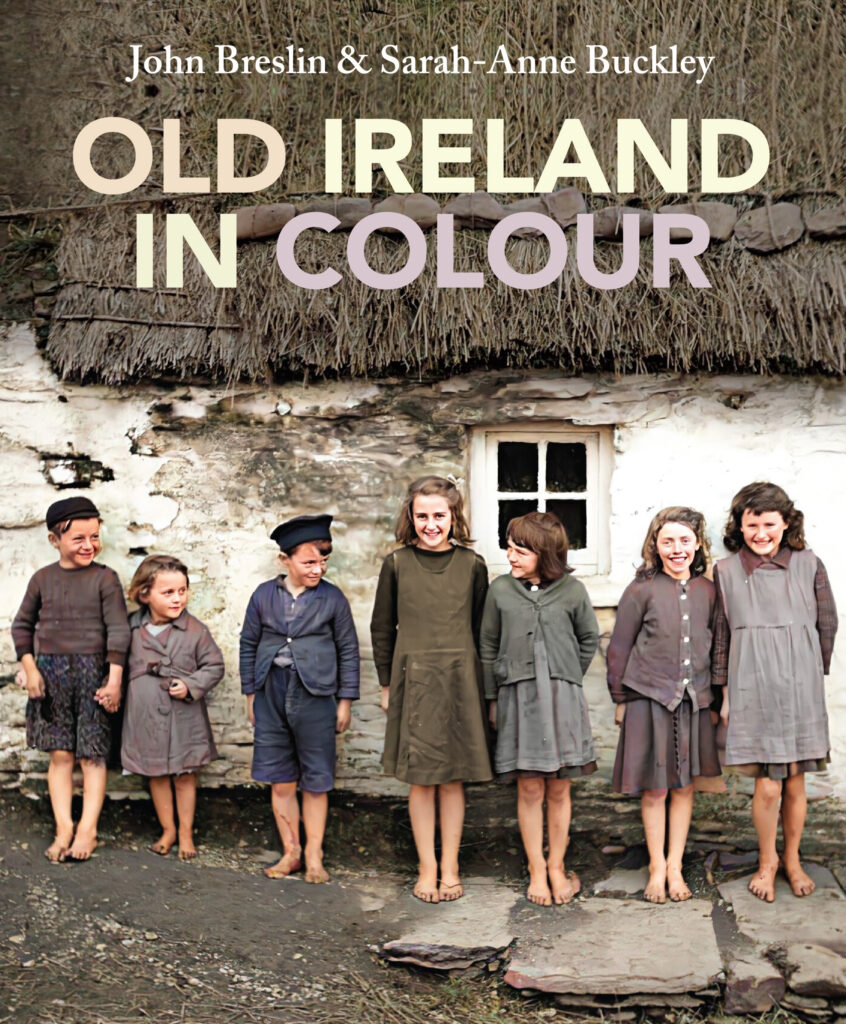

John Breslin and Dr. Sarah-Anne Buckley, who both lecture at NUI Galway, have brought our own island’s past to life in Old Ireland in Colour (Merrion Press)—a book with mesmerising images which bloom into relatability. It gives us that crucial sensation when it comes to understanding history: they were just like us.

c.1890, Newtown Castle, Ballyvaughan, Co. Clare

John Breslin has been teaching engineering, computer science and entrepreneurship for over twenty years. He began colourising old family photos at home, using AI technology. Seeing pictures of older relatives, not only when they were younger—but in colour—was amazing, John says, “but for those I had never met, great-great-grandparents and others, I found the people in the photographs to be that bit more real: when their name was mentioned, their image was clearer in my head.” This process of discovery was the genesis for collecting and colourising old photographs from all over the country.

Sarah-Anne Buckley teaches history, and is co-founder of the Irish Centre for the Histories of Labour and Class. She agrees that colour makes things “more familiar, more human—it allows people to understand context and spark curiosity.”

But it’s not as simple as running some software and standing back. The level of historical research in curating Old Ireland in Colour is staggering.

Sarah-Anne outlines the work involved in all aspects of our history: the Irish revolution; women and children; material culture; clothing; architecture; micro studies of individual places and people. A vast array of sources were consulted from the Ellis Island Records to the Folklore Collection on duchas.ie.

Together, Sarah-Anne and John’s combined technical and historical expertise and eye for detail led to the Old Ireland In Colour project, which now has a huge following on Instagram and Facebook, with the book having made over a million euro in sales so far.

Source: https://buff.ly/2ZNGsWD @NLIreland

Each page urges questions. Who was this person? What were they thinking about when the photo was taken? Who was behind the camera?

Then there are the pictures of infants in arms, children—which turn the questions more melancholy: Did they have enough to eat? Who did they grow up to be? Did they grow up? These questions are for the unknown names—or at least for those obscured from documented history, for the poor, for those not photographed in their best clothing in the good room—the group of girls playing green-grow-the-rushes-oh, the women standing by the harbour in 1905, one with a basket of fish, the other holding one in her hands—the bloodied creatures and the women long since vanished.

O’ while boys do gymnastic exercises and the teacher watches outside of Ballidian National School. Stereographs, or stereoviews, date back to the late nineteenth century, where two separate photographs were taken by cameras in slightly different positions but pointing at the same objects. A special viewer (basically a set of spectacles mounted on a stick, with a holder for the stereograph photo card at the end) allowed one to view the scene with a sort of 3D effect.

For Sarah-Anne, difficult as it is to choose favourite images, or ones that linger, the section on women and children is the closest to her own research interests as a historian of childhood, youth, and gender.

“I also research groups that have been marginalised in Irish society, so for me ‘Sublichs’ is one that stays with me. It is from the Elinor Wiltshire collection and is a photograph of two Mincéirí boys in Loughrea in 1954. It is approximately ten years before the Commission on Itinerancy which had detrimental effects for the Travelling Community in Ireland.”

“Another special image is of Mary Harris Jones or ‘Mother Jones’ who was a union activist who founded the Social Democratic Party, and helped establish the Industrial Workers of the World (or ‘Wobblies’). Aside from the Cork connections, her life story is hugely impactful, and I think she would be a great addition to any school curriculum. She is a great example of how influential the Irish diaspora have been in lesser-known areas.”

For the famous historical figures the questions are different. What were they really like?

We see W.B. Yeats, his monocled picture in its black and white form so familiar he is nearly un-noticeable in that peculiar way an iconic portrait can be, seen so many times our minds don’t pause. With colour his person emerges from the icon, the lip giving the lie to perhaps another, less public William. These are purely speculations of course, but this is the joy of the pictures in the book; they create scenarios, questions, depth, stories.

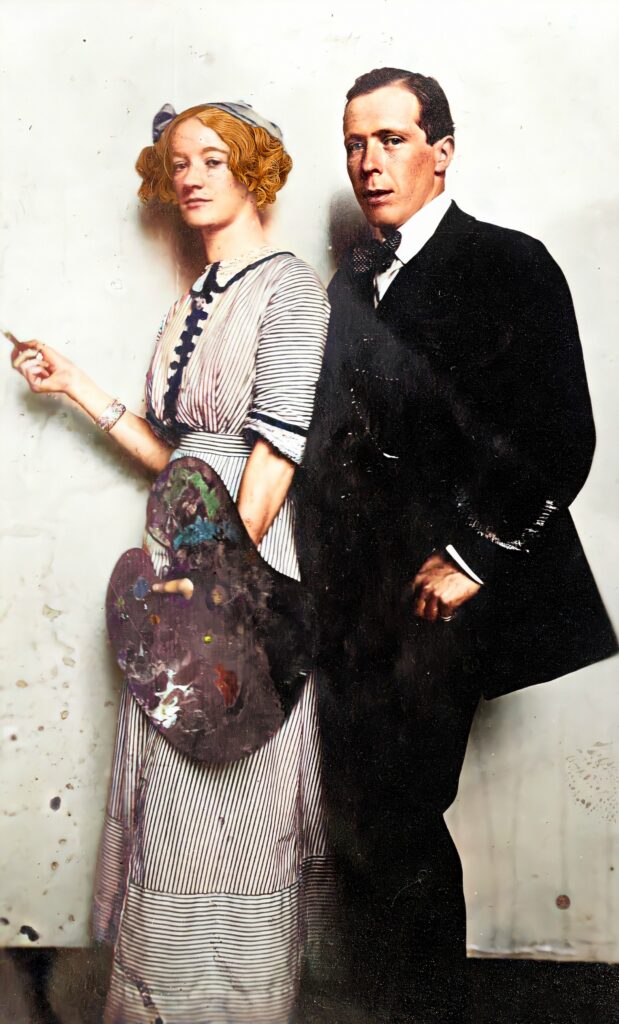

When you think of Grace Gifford, the first thought might be of a tragic love ballad, a wedding before an execution. She was a caricature artist, and when colour is added to a photograph of her with artist William Orpen, they both transform into something from the pages of The Great Gatsby.

Things that are dormant in monochrome come to life in colour, in all its ambiguity.

But recreating ‘real’ pictures can be challenging. John Breslin says that when pictures turn to colour, people’s emotions become more apparent, whether happy or curious—and sometimes scared, since many would never have seen a camera before.

“There are about a thousand people pictured in the book. Not all those faces are clear or forward facing, but it does introduce some challenges in terms of making sure that they all look as real as we can make them—whether that’s skin colour, hair colour, or clothes, etc. Even since we started working on the book in April last year, the tools that are available to help colourise, restore or enhance a photograph have themselves evolved, and I use a half a dozen different AI (artificial intelligence)-based tools in my process, including DeOldify, Topaz Labs and Remini.

Sometimes old pictures vivified in this way can feel unsettling, uncanny even, and John says this is something he tries to avoid as much as possible.

“Some of the AI tools will guess at a particular facial feature or other, and you must be careful not to take an AI recommendation as gospel, to balance it with the original features of the photograph. I was very aware watching various CGI recreations of actors (Peter Cushing, Carrie Fisher and Mark Hamill in recent Star Wars movies and TV shows) that they were not real—the uncanny valley as it is referred to. Sometimes these recreations can work well, but in terms of old photos, it’s important to leverage associated records and knowledge of a person’s physical attributes if known, referencing common clothes colours of the time, etc., rather than drifting too far into speculation. I recently animated Peig Sayers, but would have used her known eye colour, common colours for wool shawls and aprons at the time, and morphed between two photos that were taken shortly after each other.”

Then there are the seismic events; deprivation, revolution, war, strife, death—made infinitely more real with the addition of primary, secondary and tertiary colours. Blood doesn’t look like blood unless it’s crimson.

One of the images that has stayed with John is a vista of Dublin getting back on its feet after the events of 1916. “I find the 1916 Dublin in ruins photograph from the National Library of Ireland quite striking: despite the destruction, people are moving about their business, trams are running, workers are cleaning up, children are ‘supervising’ proceedings, and there is a sense of hope, despite what has obviously been a hugely traumatic and tragic time for the people.”

It’s hardly a surprise that Old Ireland in Colour was the best selling-book in Ireland last year; with or without lockdown it’s a window into other times, other worlds. It’s now making its way in the USA—where the two small girls pictured on the front cover now live.

The cover image is one close to John’s heart.

“I love our cover photograph of the barefoot children from An Fheothanach in 1946, and was so happy that the families of the three who are still alive kindly sent us photographs of each of them holding up our book—they are all still recognisable 75 years later. It makes the link between our past—as captured in this amazing photograph from the National Folklore Collection—and our present even more tangible. Eileen lives in Chicago, Kathleen in New York (both emigrated when they were young), and Seán is in Dingle.

But it’s not the sales that mean the most to Sarah-Anne Buckley and John Breslin—it’s how the pictures have affected people.

Sarah-Anne says that the book has had a very positive reaction in an older generation: “it has sparked memories, discussions (many of them intergenerational) and it has reached an audience that perhaps doesn’t always engage with history books but for whom this has really opened up different interests. It’s been the most amazing reaction, I don’t think I ever could have imagined it.”

John mentions a message he received on Facebook, from a woman who bought the book for her grandfather in Armagh.

“To say he was delighted was an understatement. The memories came flooding back; even though they weren’t from his area, he remembered the times so clearly. Then came the tears of utter joy and disbelief at how this was accomplished. You made an old man very happy with this book.”

It has also reached people whose grasp on their present reality might be slipping, to latch on to things that feel increasingly more real—their childhood, barefoot—or their mothers and fathers long-gone, forgotten streets, clothing—maybe a shawl worn by a grandmother made life-like again in russet and brown, a rhyme, a skipping rope, a boat in the harbour—those people and times that no longer-exist—but which live on again through these pictures, in breathtaking colour.