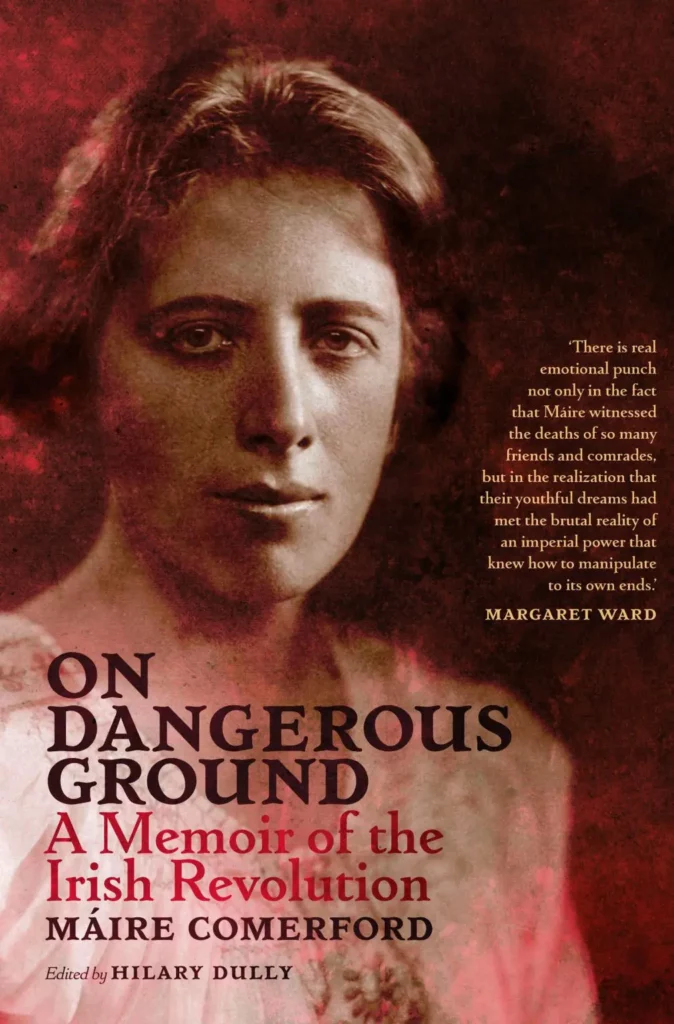

On Dangerous Ground: A Memoir of the Irish Revolution|Máire Comerford|Ed. Hilary Dully|The Lilliput Press|ISBN:978-1-84351-819-8| €20.00

“Whatever your politics and views of the past, I would recommend this book without reservation.”

—John Kirkaldy recommends On Dangerous Ground as a moving and vivid memoir.

by John Kirkaldy

This book does something important: it adds new insights and understanding to events in Ireland, 1916-mid 20s, the most analysed and described epoch in modern Irish history.

Mary (soon more often to be Máire) Comerford was born into what she described as a ‘Castle Catholic’ background. Her father owned a milling business and a grandfather won the Victoria Cross in the Crimean War and became a Deputy Inspector in the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC).

The bulk of the book was written by Máire in retirement and deposited in the University College (UCD) Library in the 1970s. Hilary Dully, a relative by marriage, has done an exemplary job in editing and has added some more of Máire’s writings.

It tells the story of a conventional middle-class background (in which horses and hunting, predictably, played an important part) to a growing involvement in republican nationalism.

The role of women in the period

Máire witnessed the Easter Rising, joined first the Gaelic League and then the Cumann na mBan, sided with the Anti-Treaty faction in the Civil War and remained a staunch republican for the rest of her life, supporting the Hunger Strikers in the North in the early 1980s.

The book encourages a re-appraisal of the role of women in this period.

Until relatively recently, for example, the role of the Cumann na mBan was often seen as subsidiary to the main events, apart from iconic figures, such as, Countess Markievicz, Maud Gonne MacBride and Kathleen Clarke.

Máire was keen to emphasise the vital importance of feeding, supplying, hiding, message carrying and sustaining the volunteers. She gives as an example from many,

‘And, when it came to hiding a hacksaw in a cake, Maa Woods was an artist. Her delicious cakes played a part in escapes from Mountjoy Prison, in 1918 and 1920.’

Women’s voluminous fashions of the time were often as asset. ‘I learnt from experience that the Lee Enfield service rifle could be carried under my coat without showing at the bottom, with my head in a big hat. With a concealed rifle each company of the Cumann na mBan could infiltrate the streets, moving from one dump to another – all thanks to the long skirt.’

Breath-taking career

Not all republicans were enlightened when it came to gender. ‘I divided the men in the Republican movement into two main categories. There were those who worked easily and naturally with women in full trust and confidence: and then there were the ‘mystery men’ who wanted us to do what we were told and ask no questions.’

Her career in these years is breath-taking. She started as the North Wexford organiser for Cumann na mBan and then moved to Dublin as secretary to Alice Stopford Green, where she met a wide range of important and influential people.

In October 1920, she began working for the Dáil Publicity Department, but in early 1921, she transferred to assisting in the White Cross organisation in reporting on the impact of the destruction of homes and factories during the War of Independence. It also distributed funds, mainly collected from America, for those who had suffered in the War.

Anti-Treaty organiser

She returned to Wexford as the anti-Treaty organiser with a budget of a weekly £5. To supplement this, she organised raids on 30 post offices, netting £80 in stamps. This gained her a reprimand from Sean T. O’Kelly; her explanation that the stamps had King George V’s head on them, all be it cancelled, was not accepted!

She was still not allowed to vote in the general election of June 1922 (being under 30; men could vote at 21) but used the ballot paper of an older woman, who had died.

Some of the most graphic descriptions in the book are of the bombardment of the Four Courts (April-June 1922).

Kidnappping plot

In January 1923, Máire was involved in a plot to kidnap William Cosgrave, the Prime Minister of the Free State. She was arrested, having been informed on by a former colleague, Min Ryan.

She had spells in Mountjoy and Kilmainham prisons; was shot in the leg by a soldier; managed to escape once; and endured hunger strikes.

Éamon de Valera sent her on a propaganda mission to the United States in late 1923 (travelling om a false passport as Edith Lewis), where she stayed for nine months.

Predictably, Fianna Fáil’s decision to break in 1927 with Sinn Féin’s traditional policy of abstention, came as a bitter disappointment. Máire retired from active politics but never renounced her republicanism and tried to scrounge a living as a poultry farmer.

Whatever your politics and views of the past, I would recommend this book without reservation. (How many people fifty years ago would have bet on a Fianna Fáil/Fine Gale coalition?)

It would be difficult to write a dull book about this period (a few have tried) but Máire is a gifted writer in the Swift/Orwell tradition of simple and clear English.

De Valera made amends – to an extent – by getting her a job in 1935 as Women’s Editor of the Irish Press, a post she held for 30 years and which gave her some financial security.

Vivid and moving

There are many vivid descriptions of incidents and places; perhaps the most moving is the death of Cathal Brugha at the Hamman Hotel. She is particularly good at character sketches of many of the leading figures.

The reader is supported by a good introduction from Margaret Ward, some very helpful footnotes and some interesting photographs. An added bonus is an appendix with some press cuttings from British and American newspapers from 1923.

Even the Daily Mail, not known for its enthusiasm for Irish nationalism, described her as ‘the Jeanne d’Arc of the republican cause’ and commented with amazement at how she, in the middle of a gun battle, ‘coolly cycled down Sackville Street’.

Dully in her introduction writes, ‘as editor of her memoir, I can only hope that almost forty years after her death, I have served her intentions well.’

The book shows that her hopes have been more than realised.

John Kirkaldy has a PhD in Irish History, worked for many years with the Open University and has been reviewing for Books Ireland since 1980. He has contributed to three Irish history anthologies, a school textbook, and has been involved in a number of Open University History documentary series. Aged 70, two years ago, he went round the world on a much delayed gap year described in his book, I’ve Got a Metal Knee: a 70-Year Old’s Gap Year.