Eighty years ago, the writer, actor and singer Richard Hayward set out on his journey down the River Shannon for a book published in 1940. For his new travel book on Ireland, Paul Clements has been on a meandering trip down the Shannon, following Hayward’s route. His journey was carried out over a twelve-month period from late spring 2017 to early summer 2018.

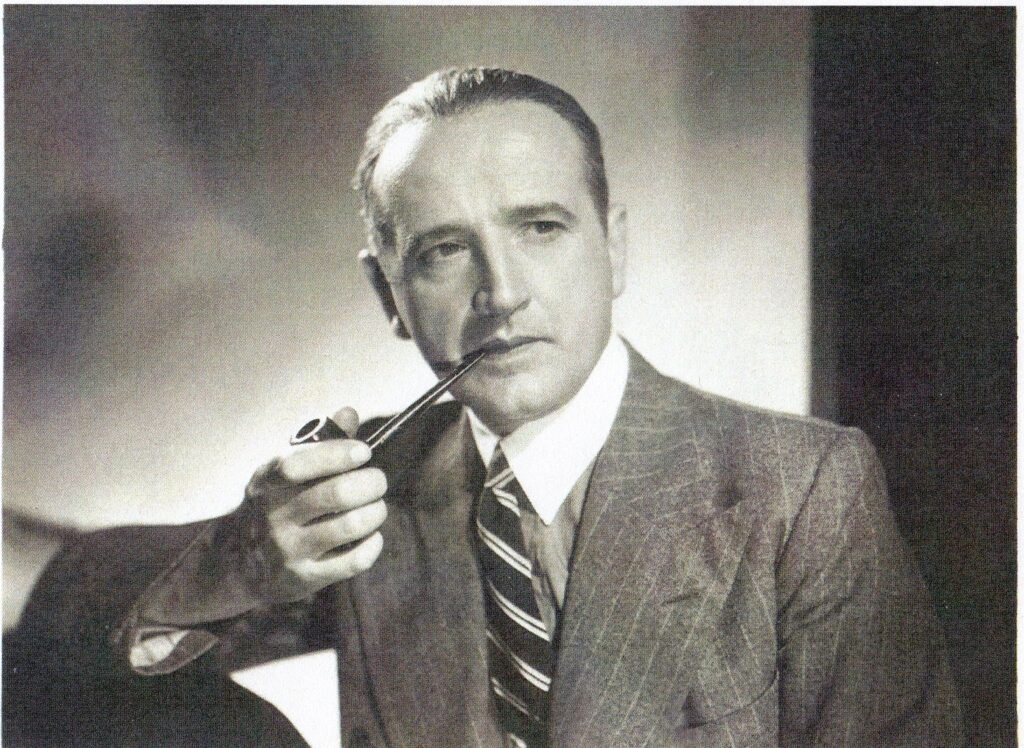

Rivers are perfectly calibrated to the requirements of travel writing and the River Shannon is no exception. From the Shannon Pot in Cavan to the estuary, it is a ready-made linear journey but, of course, that does not mean that it has to be followed strictly, since meandering is the best approach. Travelling this way means you pick up stories, personalities from the past, long-forgotten information and meet present-day characters. That is exactly what Richard Hayward (1892–1964) did for his trip along the Shannon in the summer of 1939, when Ireland was a young and impoverished country still trying to find its feet in the decade following partition.

Hayward was noted for his travel books on the country and explored the river in August 1939, just two weeks before the outbreak of the Second World War. His book, Where the River Shannon Flows, topped The Irish Times non-fiction charts under a section called ‘What Dublin is Reading’ when it was published in 1940.

Since then, the river has nourished artistic souls and influenced many writers. Numerous epithets have been applied to it by travellers, poets, musicians and other chroniclers. The most overused adjective is ‘majestic’, but it is also frequently referred to as ‘lordly’, ‘mighty’, ‘spacious’, ‘noble’, ‘slumbering’ or ‘stately’. Hayward classified it as ‘the great mother river of Ireland’. The Kerry novelist Maurice Walsh, who wrote the foreword to Hayward’s book, called the river ‘immense’. He said it once separated the Pale from Hell—‘though there was a small dispute as to which side Hell lay’.

The elegist of the midlands John Broderick was less flattering, referring in The Waking of Willie Ryan to the river’s ‘silent, menacing presence’. Writing in his autobiography Nostos, the Kerry-born poet, mystic and philosopher John Moriarty described the estuary from Tarmons Hill, near Tarbert, as ‘A grandeur of water … the Shannon flowing through it with a landscape that had in it a remembrance of Paradise’. In the final passage of James Joyce’s short story ‘The Dead’, he writes of the ‘dark mutinous Shannon waves’.

One literary connection to the Shannon that is not so well known is the fact that Flann O’Brien’s novel At Swim Two Birds takes its title from an island on the river between Clonmacnoise and Shannonbridge. As part of my quest, and as a dedicated ‘Flannorack’, I set off by bicycle to try to pin down information about two small islands that I had come across on an old map: Curley’s Island, and just south of it, Devenish Island, or Snámh-dá-Ean (literally ‘Swim-Two-Birds’). In the Anglo-Norman era, Curley’s Island was guarded by the castle of Clonburren on the west side of the river. Some accounts also state that St Patrick crossed the river into Connaught at this point.

The road from Shannonbridge follows hedges overflowing with cow parsley and bright yellow gorse. When I reached the riverside callows, I came across a fellow cyclist and dog-walker, who introduced himself by the name of Flan—a serendipitous encounter, which the author himself would have enjoyed, even though he spells his name only with one ‘n’. Flan Barnwell was exercising his dog, Guy, who reconnoitred the ground with the careful nose of a detection dog sniffing for marijuana. We talked about the title of the O’Brien book and walked across the callows to get as close as we could to the edge of both islands. Curley’s Island is a thin strip of grass and sand of six acres to the north of Devenish Island. There is an architectural grandeur to the lofty tottering reed beds that rise with a towering palisade of stems up to six metres. When we reached the river we could make out the division with one part falling down like a finger to Devenish. Cattle were relaxing on the island, in no hurry to move anywhere.

It was intriguing to discover that At Swim Two Birds exists as a real place. I recall a quotation from another of O’Brien’s books, The Third Policeman, celebrating the romance and mysticism of cycling: ‘How can I convey the perfection of my comfort on the bicycle, the completeness of my union with her, the sweet responses she gave me at every particle of her frame?’

O’Brien’s molecular theory stated that bike and rider eventually become one through ‘arse-saddle symbiosis’, meaning that you are not sure whether you are talking to a bike or its rider. If you spend too much time in the saddle then by some unscientific process of energetic exchange, you will yourself become a bit mechanical. O’Brien sums it up: ‘You would be surprised at the number of people in these parts who are nearly half people and half bicycle.’ A light shower began to fall as I cycled back to Shannonbridge, a spring in my pedalling. With the music of stream-song and spoke-song in my ear, I called to mind another quotation from The Third Policeman: ‘What could be more exquisite than a countryside swept lightly by cool rain’.

Shannon Country: a river journey through time by Paul Clements is published by the Lilliput Press at €15. His biography Romancing Ireland: Richard Hayward 1892–1964 is also published by Lilliput at €20. Both are available from bookshops or from www.lilliputpress.ie.