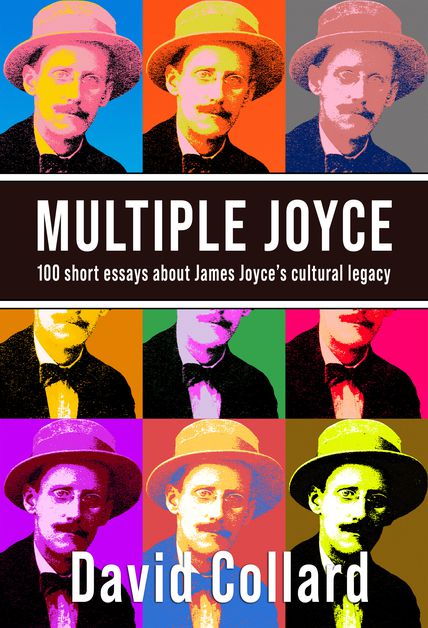

Multiple Joyce|David Collard|Sagging Meniscus Press|€20

“…a sparkling and vivacious probe into a fresh spectrum of Joycean subjects…absorbing, upfront, funny, erudite, and charming“—Nuala O’Connor

by Nuala O’Connor

If you like your essay collections smorgasbord-ish, then Multiple Joyce is for you. If you enjoy pop culture and fun, both gently and fiercely poked, it’s for you. If you love all things Dubliners, Portrait, Ulysses, and the Wake, then Multiple Joyce is for you.

The book is subtitled ‘100 short essays about James Joyce’s cultural legacy’ and, though everything from the familiar to the far-out regarding Joyce has been mined by scholars, Collard uncovers some truly obscure talking points.

Sparkling and vivacious

It is hard to do justice to the range of topics here, or to the reading experience, which is enhanced by Collard’s off-beat, amiable sensibilities but, I can say, Multiple Joyce has shot to the top of my favourite Joycean books.

This volume sits comfortably alongside luminaries like Ellmann, Maddox, and Kevin Birmingham, who have all tackled Joyce brilliantly, but Multiple Joyce offers a sparkling and vivacious probe into a fresh spectrum of Joycean subjects.

Ghost in the machine

Collard’s introduction tells us his book was written in London during the pandemic lockdown, and he relied on just his own library and the internet for research. ‘This unexpected restraint became a liberating advantage,’ he writes, ‘because, as I soon realised, Joyce is a ghost in the machine with…130,000,000 online citations.’

Collard began by looking at the many forms of commodification of Joyce, noting that Joyce’s presence – in objects bearing his face, or quotes from him – reflects ‘the values and priorities of our hyper-consumerist, late capital times’. Collard found everything from pyjamas to teabags emblazoned with Joyce’s image and/or his words.

Meet Finnegan Wake™

The opening essay sets the tone; in it we find a potent mix of humour, fairness, wonder, and resignation in a piece entitled ‘Meet Finnegan Wake™’. This essay – the genesis for the book – began like one of Joyce’s epiphanies, but it took place in the prosaic environs of a Toys “R” Us shop, in London.

There, the author tells us, he encountered for the first time a doll called Finnegan Wake™, a character from the Gothic children’s animated TV series, Monster High. Finnegan, a ‘wheelchair-using teenage punk merman’, pinged a moment of ‘whatness’ for Collard, and the idea for Multiple Joyce began to flicker dimly.

The author correctly deduced that ‘if Joyce’s work could percolate into the wider world in such an indirect and possibly unacknowledged way’ – as a plastic mer-goth – there must be many similar examples abroad.

After encountering Master Wake and wondering about other instances of Joyce’s ‘cultural aura’, Collard tapped the words James Joyce into a search engine, coupled with other cultural phenomena.

By this method he found Kim Kardashian who – according to the app I Write Like – writes like none other than James Joyce.

He found Father Jack Hackett of Father Ted fame, whose famous monosyllabic rallies (Drink! Feck! etc.) are analysed in terms of their frequency in Ulysses. (Drink = 62, feck = 0, for those who need to know).

Wide-ranging lens

Naturally this search for Joyce + AN Other brought many wondrous, amusing results but, in the essays – in case anyone is worried about an excess of levity – Collard also weaves in his own encyclopaedic knowledge of Joyce and his writings.

There are as many high-brow as low-brow entities and entries in these pages, and that heady admixture is what makes the book so enjoyable.

Collard’s wide-ranging lens takes in contemporary writers – and Joyce devotees – like Conner Habib, Susan Tomaselli, and Eimear McBride, as well as issues of interest to culturally-minded Irish people, such as the wilful destruction of the House of The Dead, on Usher’s Island in Dublin.

Joyce set his masterpiece short story in the building, but it will shortly be turned into a tourist hostel, thereby ensuring visitors will, once more, have a place to sleep, but little of interest to visit, thanks to our artistically barren ‘planners’.

As Collard ruefully notes, ‘Joyce’s cultural legacy is apparently more secure on the internet than in the real world.’

Subjects and side-rivulets

Other subjects that hove into view for Collard are the essential nature of Nora Barnacle, and other women, to the entire Joyce project. He also examines the reviews Joyce endured for Ulysses, especially a ‘blimpish’ one by poet Alfred Noyes, which spoke of the book’s ‘imbecile pages.’

Collard digs wonderfully at Noyes, and the poet’s editor, as well as the readers of the Sunday Chronicle with this essay’s ending: ‘The philistine is always confident, always indignant, always confused, seldom interesting, usually on the right politically, and always, always wrong.’

7 Eccles Street, the home of the Bloom family in Ulysses, is given its own essay called ‘Eccles Street Revisited’, outlining the building’s importance, demise, and destruction (what’s new?).

He examines Eccles as a placename, including the home of the eponymous cake in Lancashire, England, and some ‘wonky speculation’ about Ecclesiasticus in Joyce’s novel Portrait of the Artist. These side-rivulets make for great reading throughout the collection – Collard is skilled at forging unusual but relevant connections, and will also admit to bafflement at times.

Smorgasbord and salmagundi

The Eccles essay closes with the author trying to work out a mistake, and he tells the reader, happily, ‘Is the error Joyce’s?…Without a moment’s hesitation I can tell you that I have no idea.’

I called this book a smorgasbord at the start; it is a salmagundi, too, but a cohesive one, a rare, delicious treat for readers, and a book that would have tickled Joyce, with its vibrant potpourri of playfulness, punning, and pathos.

Essay 100 is, of course, a multiple-choice affair, a worthy finale for a book of multiplicities, proving Collard as a skilled excavator of the Joyce legacy. In his introduction, though, he warns the reader that neither purists nor doctrinaires will find Multiple Joyce appealing.

I question that view, however, because, in my experience, the person who is seduced by Joyce is often seduced by everything related to Joyce. And I defy Joycean purists not to be totally beguiled by this absorbing, upfront, funny, erudite, and charming book.

Nuala O’Connor is the author of Becoming Belle (2018), Miss Emily (2015), The Closet of Savage Mementos (2014), You (2010) and six short story collections, her most recent being Joyride to Jupiter. Her fifth novel, Nora, is about Nora Barnacle, wife and muse to James Joyce, published in Ireland in April 2021 with New Island, and is the One Dublin One Book for 2022.