You Will Dye at Midnight|Donal McCracken|Wordwell|ISBN: 978-1-913934-16-3|€20.00

“As well as landlords and agents, threatening letters were sent to large farmers, small farmers, middle-men, sub-tenants, ‘land grabbers’ and even shopkeepers.”—Tony Canavan on You Will Dye at Midnight, by Donal McCracken

by Tony Canavan

The sending of threatening letters has a long history in Ireland.

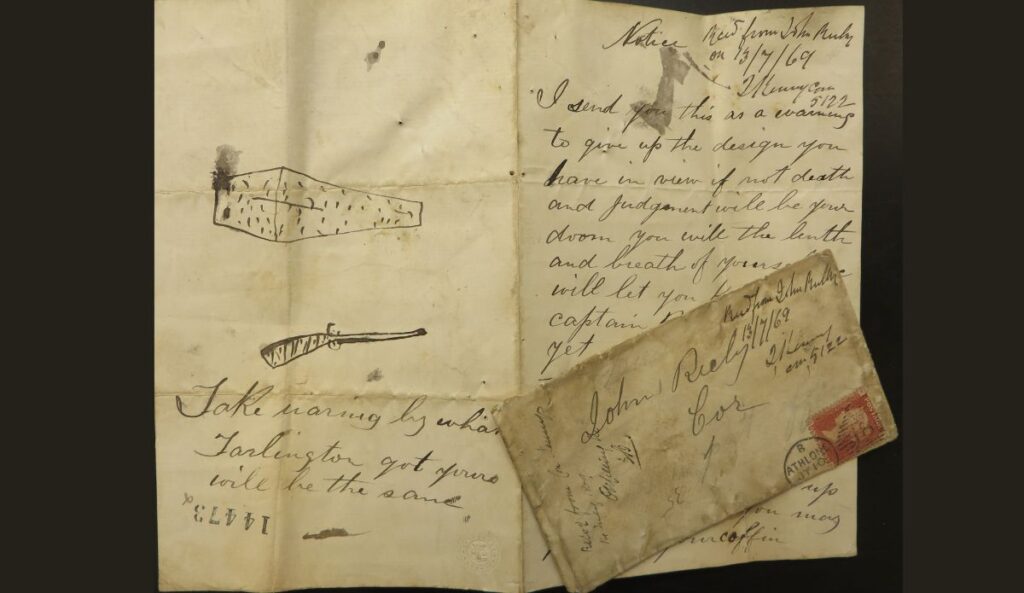

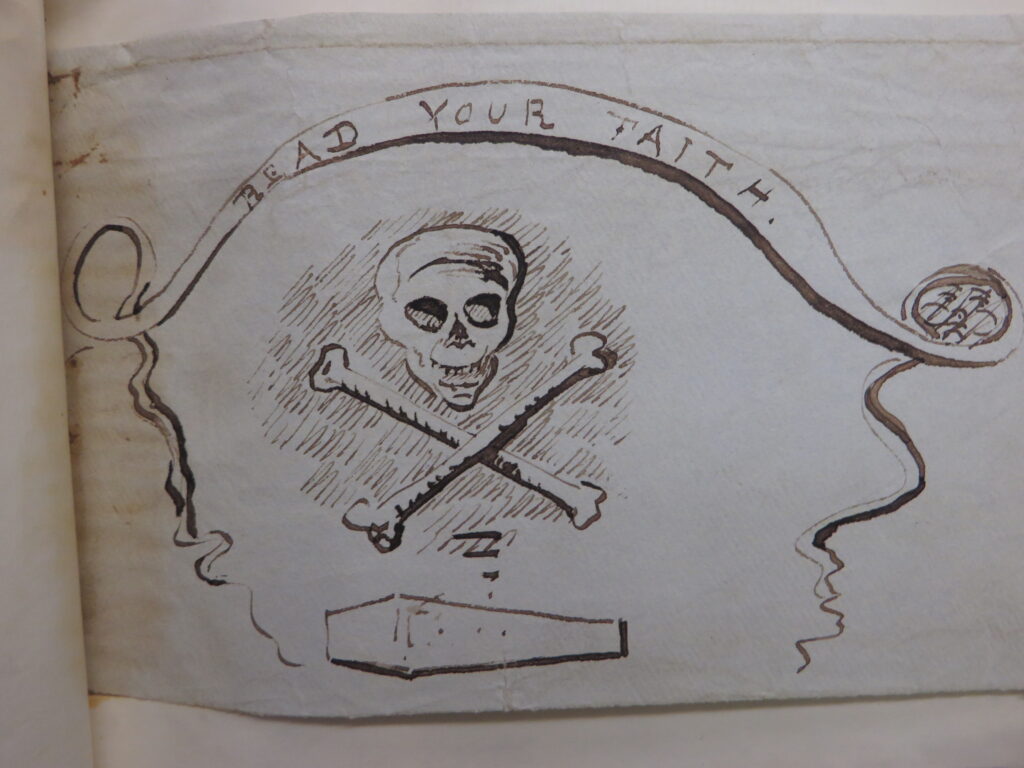

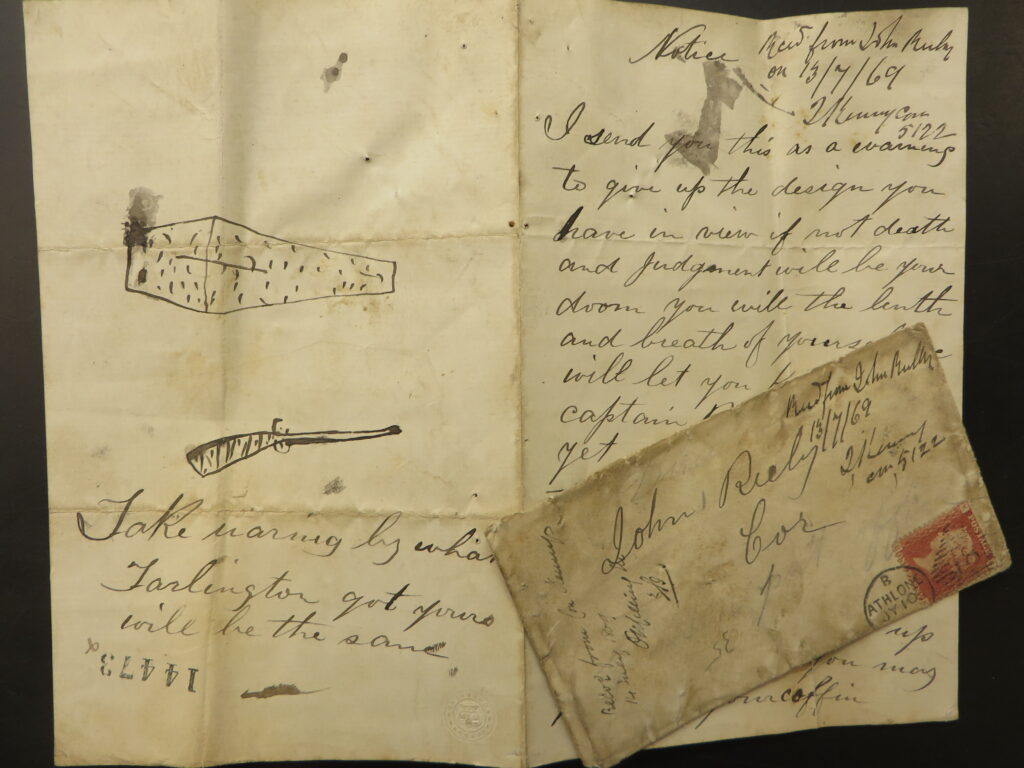

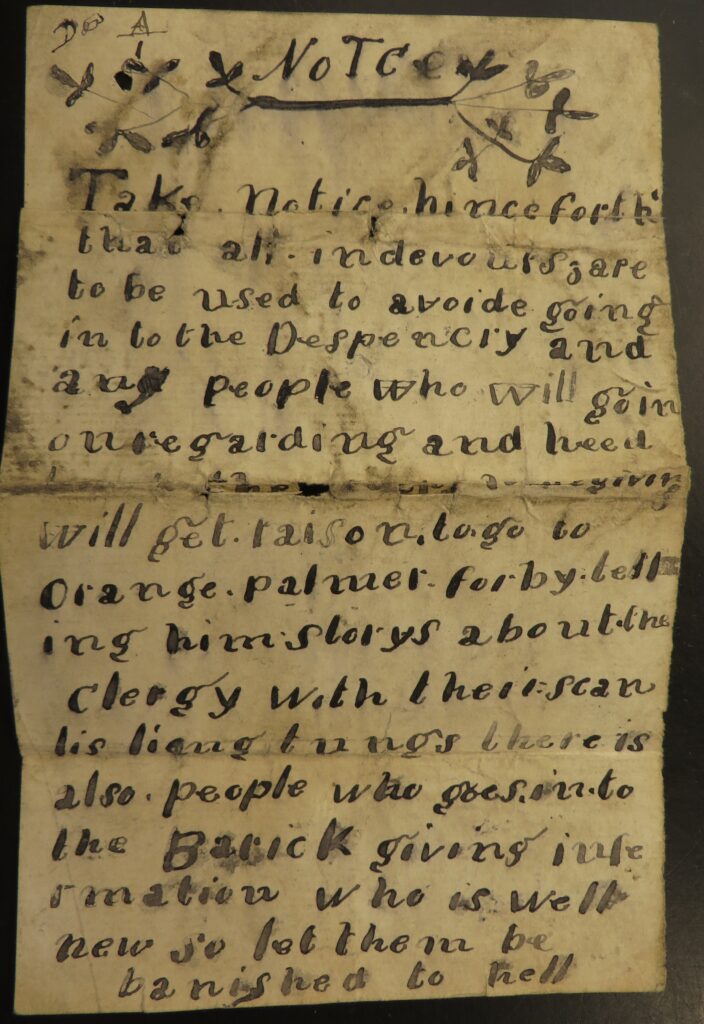

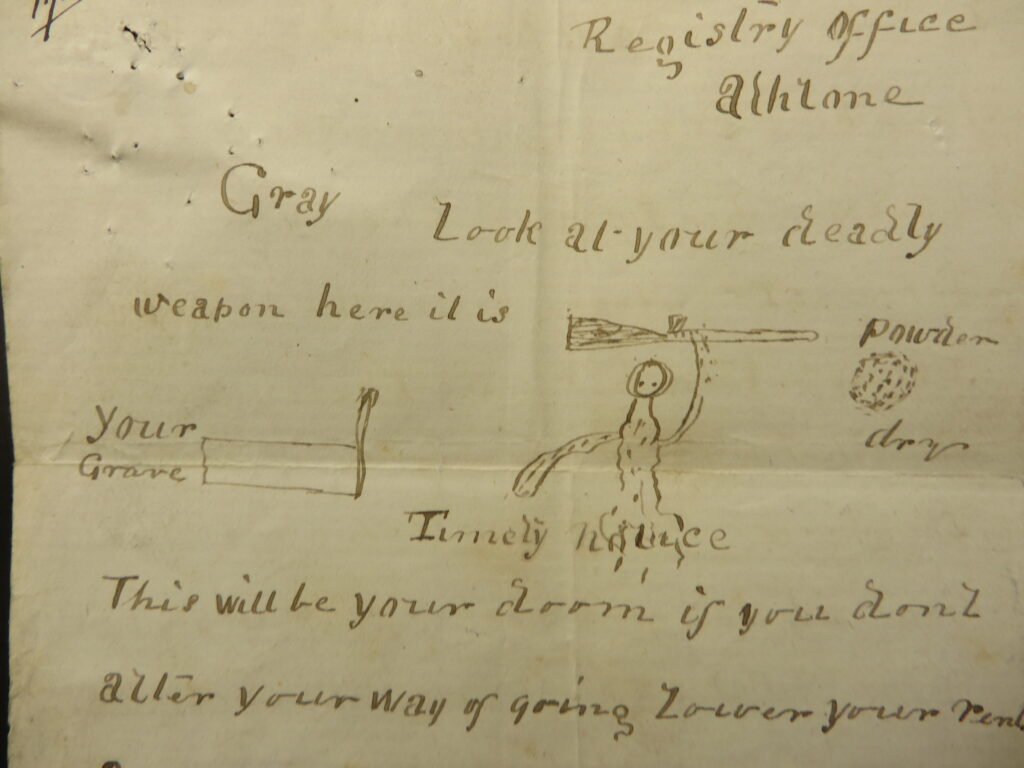

I first came across them while researching my postgraduate thesis on the Hearts of Steel, a secret agrarian society in eighteenth century Ulster. The main object of such letters were landlords, their agents and Church of Ireland clergy. They usually expressed anger over unfair evictions, high rents and prices, and paying tithes to the established church. Their aim was to terrify the recipient into doing what the letter writers wanted.

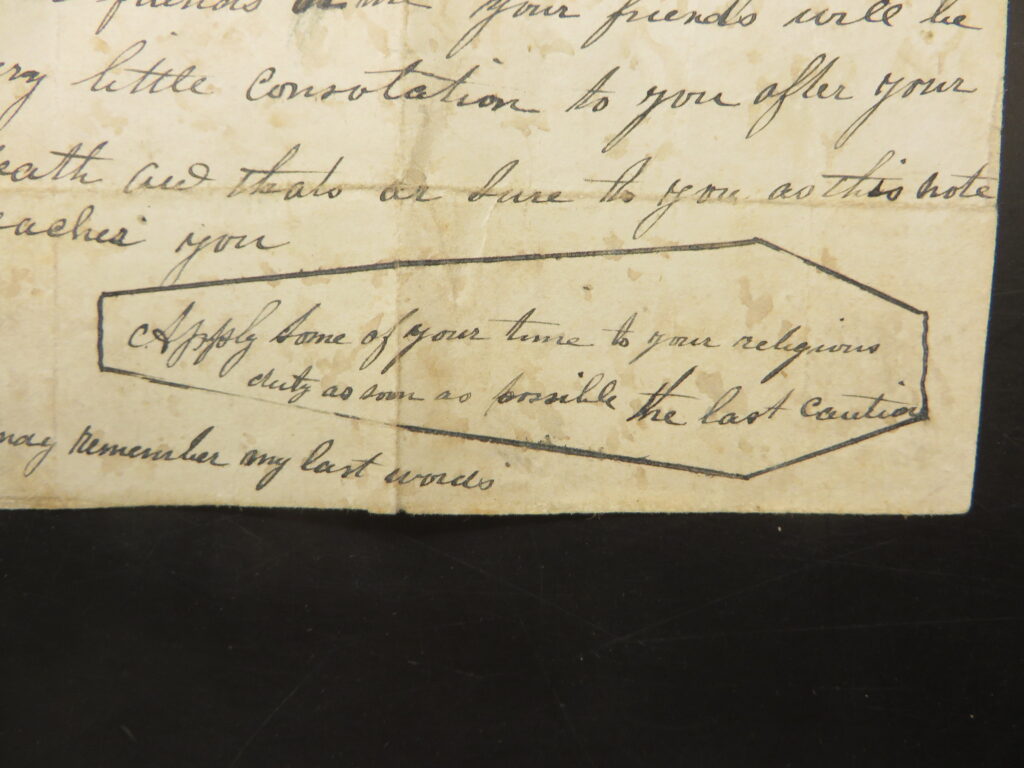

Violence or death often followed if the letter was not obeyed.

This practice carried on into the Victorian era, as McCracken’s detailed and informative book shows. The grievances remained much the same, except that payment of tithes became redundant.

Letters and response

McCracken’s book is divided into two sections. The first looks at the letters themselves while the second considers the response from the authorities and society in general.

He reveals that 36,305 threatening letters were recorded by the constabulary during this period—many more than were recorded in Britain.

The figures are probably not accurate in so far as there were some issues over how the letters were recorded—particularly once they were classified as ‘outrages’, blurring the line with actual acts of violence. On top of this, not all such letters were reported to the authorities and many were destroyed on reception. However, many people did keep the letters and these provide the basis for much of McCracken’s research.

Agrarian phenomenon

It is possible to draw an accurate picture of the letters, their content, import, who sent them and who received them. Two striking facts that emerge are that they remained a mainly agrarian phenomenon, despite there being grievances in towns and cities, and they indicate a high degree of literacy among the Irish. McCracken attributes this literacy, ironically, to the success of the national school system.

Another irony is that the Royal Mail’s penny post enabled the delivery of letters anonymously.

Before this, such letters had to be delivered by hand. Their distribution was not evenly spread throughout the country: with the exception of south Armagh, there were relatively few written in Ulster while Munster seems to have been a hotbed of rural discontent.

Wide range of targets

Despite the popular perception that landlords and their agents were the main victims, the range of recipients is wide and varied. As well as landlords and agents, threatening letters were sent to large farmers, small farmers, middle-men, sub-tenants, ‘land grabbers’ and even shopkeepers.

Outsiders, even from the neighbouring parish or townland, were also targets for a number of reasons, such as taking over a tenancy or doing jobs which locals could do.

McCracken identifies personal or venal interests as the motivation behind some letters but also recognises that the prevalence of secret societies in Ireland (from the Ribbonmen in the early period to the Fenians later on) had significant influence on the writing of these letters.

Indeed the frequency of threatening letters corresponds to periods of distress or social upheaval, such the Great Famine or the Land War.

Language

Interestingly, even though Irish was the language of the majority, these letters were written in English—perhaps a reflection that the majority of recipients were English monoglots.

McCracken has a few things to say about the language used in the letters. Most were short and blunt, only a few displaying rhetorical flourishes or sophistication. He concludes that the letter writers were not the poorest section of society—who were too intent on just surviving—but the better off farmer, shop clerk, or even a local schoolmaster.

Not only were a variety of pseudonyms used, such as Captain Moonlight or Rory of the Hills, but usually it was not the person with a grievance (such as an evicted tenant) but someone else, such as a relative or local agitator, who sent the threats.

McCracken states that some people were well known as letter writers to whom others would go to have a letter written. The local police often knew who this person was but found it hard to obtain a conviction.

Reaction

This brings us the second section of the book which examines the reaction to the letters. This depended very much on class. The tenant farmer or small businessman would often take these threats seriously, fearing death if they did not comply. On the other hand, the land agent or landlord usually defied the letter writers to do their worst.

Many had a military background and McCracken paints a jolly picture of such people going around armed, prepared to take a pot shot at any potential attacker.

Threatening letters were widely viewed as ‘fair warning’ to quit your ways or be killed.

Some landlords and agents were killed after receiving threats which is why some recipients sought protection from the RIC who seemed happy to provide bodyguards or extra patrols.

The work of the constabulary was supported by the military, and facilitated by coercive legislation. Successful prosecutions were still few and far between, leading many landlords to employ ‘emergency men’ as bodyguards or workers on an estate after boycotting became a weapon of the Land League.

Settlement of the land question

In the 1880s an Irish Loyal And Patriotic Union was established to assist such landlords and resist the Land League campaign. I’m not sure that everyone would agree with McCracken’s assessment of the character of the ILPU, or of the emergency men.

In the end it was the settlement of the land question that led to the decline in threatening letters as grievances were addressed. However, the practice of sending such letters persisted decades after the land campaign ceased. They were a feature of the upheavals of the War of Independence and after.

Although it is beyond the scope of this book, it might be argued that it continued, or was revived, in the Northern Ireland Troubles.

This is a landmark book that provides the first comprehensive examination of threatening letters in Ireland. With its many charts and maps, it looks at every aspect of the subject. McCracken provides new insights into these letters, their authors and recipients, debunking many myths on the way and providing a solid analysis of the subject.