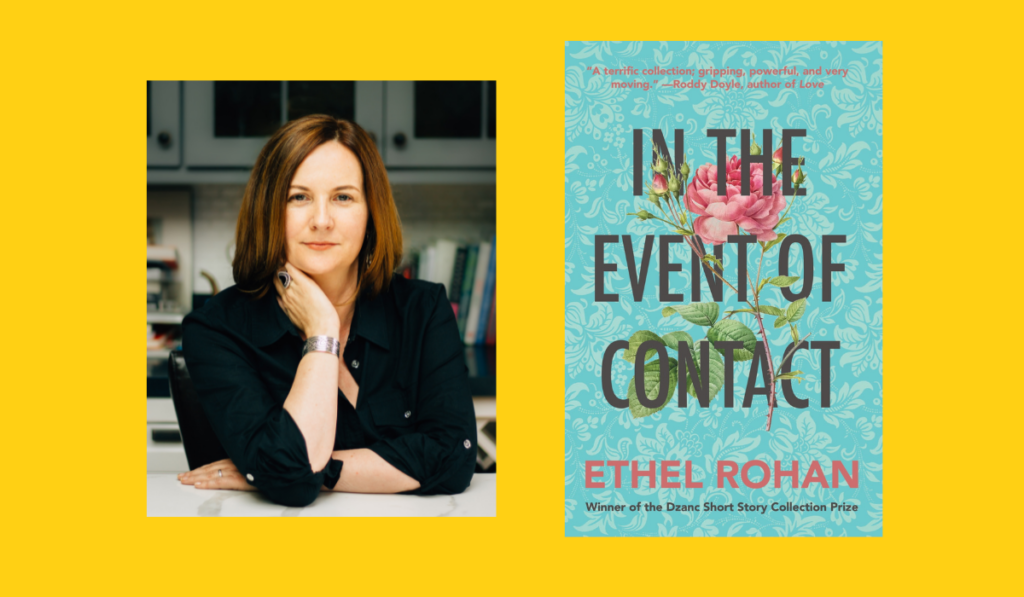

In the Event of Contact|Ethel Rohan|Dzanc Books|ISBN: 9781950539260|€13.00

Read the first part of Rare, But Not Impossible, one of fourteen stories in In the Event of Contact by Ethel Rohan, winner of the Dzanc Books Short Story Collection Prize.

“This is a terrific collection; each story is its own thing, gripping, powerful, and very moving.” —Roddy Doyle

Margo entered Dublin Airport’s arrivals hall alongside her fellow passengers, facing into the swell of waiting family, lovers, and friends.

She looked away from the various emotional reunions, her throat thickening just as it had during the airplane’s shaky descent, when she’d sighted the familiar patchwork of green fields through the window. Every time she returned, that first glimpse of home made her teary. She scanned the last of the expectant crowd, knowing no one was there to meet her and yet half hoping. Her parents were waiting for her at home—the trek to the airport too inconvenient and risky to their minds, its roads treacherous, its large roundabout lethal.

Shrieks sounded from the small group to Margo’s right, another thirty-something daughter like herself back from New York.

A watery-eyed family circled the willowy woman and clasped her inside thick arms sheathed in dark, rain-splattered vinyl, their voices full of the sunny weather that Margo wished was awaiting her. In the ten years since she’d emigrated, she had flown home maybe a dozen times, and every trip the sky spilled. She fixed on the exit doors and hurried toward the taxi rank. Inside the walkway’s glass tunnel beaded with rain, her floral-patterned suitcase dragged after her with a scraping sound, its front splashed with a strip of red tape that warned Heavy.

*********

Just once, Margo would like to not be grilled by Ireland’s chatty taxi drivers.

The grey Skoda had yet to hit the M50 and already Anthony, hefty and care-creased, had uncovered her pertinent details. Still, he wanted more. She reluctantly revealed she was a hairstylist—omitting that she owned a thriving salon in Greenwich Village—and was home for a friend’s wedding.

“I hear the American accent now, all right.”

He laughed, a dog’s yap. Margo suspected he went by Anto. She turned her head to her window, the rain still pelting. In recent years Dad had taken to calling her “the Yank.” Her whole life, people criticised her voice—too posh for her Northside, working-class neighbourhood when she was a girl; not Irish enough in New York City; and too American in Ireland. No matter where she was, she never sounded like she belonged.

She felt Anthony watching her in the rearview and kept her gaze trained on the lanes of speeding traffic to their right. Beyond the teeming motorway, a fresh crop of concrete buildings punctuated the endangered stretch of trees and fields.

Anthony’s phone rang, a new, fancy Nokia with Internet. “Hiya.”

A woman’s voice tore the air.

“What do you want me to do about it? She’s your sister,” Anthony said. Another burst from the woman. “Stop letting her wind you up,” he said. She continued her screed. “I’ve a fare, I have to go.” He thrust his arm between the front seats, aiming the phone at Margo. “Say hello. She doesn’t believe you’re here.”

“I’m here.” Margo’s voice came out thin and hollow. She was here, alone, her husband, Kevin, left behind in New York.

“Satisfied?” Anthony ended the call. “Sorry about that.”

“It’s okay,” Margo said.

“I reckon the wife and her sister will kill each other one of these days. I’m rooting for the sister,” Anthony said.

When Margo was young she’d longed for sisters and brothers, a big family.

It was what her parents wanted, too, but Mam had haemorrhaged after delivering her and underwent an emergency hysterectomy. In her teens, Margo came to accept, and eventually cherish, her solitary standing in the family.

Anthony popped a toffee into his mouth and tossed its wrapper out the window. Margo swallowed a cry of protest, her head turning, watching the wrapper’s flight. When she was nine or ten, she’d won her school’s anti-litter poetry competition, her prize a handsized glass flamingo. The exotic bird was filled with pink liquid, and its colour would magically drain and refill with a flick of the wrist. Her family, friends, and neighbours had marvelled. “It was made in America,” she said, impressing them further. It hadn’t occurred to her until now that perhaps the flamingo was the first spark of America’s pull. That, and her wanting a bigger life than what she’d had here.

*********

Mam sat opposite Margo at the kitchen table while Dad remained on his armchair in front of the blaring TV, the sports commentator narrating a horserace with shrill excitement. Mam looked plumper, and Dad thinner, and both their faces were more lined.

The kitchen, the entire house, looked much the same.

Dad aimed his pen above the newspaper’s racing forms, recording his wins and losses. He claimed he only ever bet pittance, but monitored each race as though he’d gambled his life savings.

“Eat up,” Mam said, nudging the greasy, heaped plate closer.

Margo used to crave these staples from her childhood, especially the fat sausages and thick slices of brown bread slathered in butter, but she’d gone off fatty, processed foods in recent years and would much prefer fresh fruit and granola with a dollop of yoghurt. If she admitted as much, her parents would say she’d been living in America too long. She felt a little sick, her stomach out of whack from tiredness and the questionable airplane food.

“I’m full, thanks.” She pushed the plate away, the two discs of black pudding staring up like large, empty eyes.

Mam ran her hand over her flattened, grey-brown hair. “I’m a holy show. I waited for you to come home to colour it.”

“I’ll take care of it first thing in the morning. I brought the best of products.”

“That’s all right, I have my own stuff I like.”

Margo swallowed the urge to coax. Her parents had never said it aloud, but they thought she’d gotten a bit big in herself in America. She felt the need to watch what she said around them, and everyone else here. To put herself down in good measure.

“It’s a pity Kevin didn’t come,” Mam said for the second time. She and Dad loved Margo’s husband of six years and had often congratulated her on finding a grand Irishman in America. “We wouldn’t have wanted you to wind up with a foreigner.”

“I told you he’s busy at work, and the airfare’s scandalous. Plus he has to come back for his brother’s wedding in December.”

Dad half came out of his armchair, goading his horse on.

His bet won and he shot to his full height, his arms straight up in the air. He was less excited earlier when he’d met Margo and her suitcase at the front door. She recalled his rare hug with a warm feeling, his smell minty from the numbing cream he rubbed into his joints. He never failed to embrace her on her arrival, but it was a one-way gesture. The night before her departure, her parents religiously pretended they would see her at breakfast, but neither of them ever got out of bed to say goodbye. She supposed she also preferred dodging that pain.

She thought to phone the hair salon, to check in, but remembered the time difference. Over there, dawn was only breaking. She pictured Kevin in bed, her side of the mattress empty. Her head started to spin, faint from lack of sleep. “I’m going to lie down for a bit.”

“You just got here,” Mam said. She and Dad didn’t understand jetlag, or appreciate the time and effort it took to get to them. Homebirds, they’d never travelled farther than England, and now, in the raw wake of 9/11, there was no way she was ever going to convince them to at last visit “the Big Apple.”

As Margo climbed the stairs, Mam said, “She looks pale.”

*********

Margo’s childhood bedroom never changed—narrow, sparse, and a soft pink paint that coated even the ceiling.

She was getting between the covers patterned with a field of buttercups when the telephone on the hall table rang. Even that sound was different in America.

Mam answered, her low voice carrying up the stairs. “She just went to bed, she’s absolutely wrecked. Do you want me to go get her?” Kevin obviously said no, let her sleep.

Margo lay awake, fighting the urge to jump up and start punching the wall. After years of blameless service, her IUD had shifted out of place, rendering it useless. “Rare, but not impossible,” her ob-gyn said. Margo could still see the pregnancy test stick, those two pink-red lines.

She and Kevin had never wanted kids. Their lives were full, rich. Margo booked an abortion. Kevin anguished.

“Maybe the baby’s meant to be? Maybe fate is smarter than us?” he said.

“So you’re going to fail me, too?” she said.

Margo circled the supermarket’s car park, searching for a vacant space while Mam fretted on the front passenger seat. “I don’t like these new underground garages. All the rows and floors. Your dad can never remember where he left the car.”

Margo spotted a parked van with its reverse lights on. She rolled

Dad’s Escort to a stop in the middle of the aisle and waited, shaky, fog-brained. She’d drunk too much red wine at Brigid’s hen party. Mam hummed nervously, loudly. The van rolled away, and Margo glided into the vacated spot. Mam jotted down the space’s number and floor.

“I would have remembered,” Margo said tightly.

Inside the busy supermarket, the noise and bright lights brought back the pounding headache Margo had woken up with. Janet Jackson’s “Doesn’t Really Matter” piped from the sound system. Margo, Brigid, and her brood of hens had danced and screeched to that same song inside the throbbing, neon-lit nightclub.

“You sound so American,” Brigid’s chief bridesmaid said at the start of the night.

“Doesn’t she?” Brigid said, laughing.

When Margo admired a hen’s designer “sneakers,” the group snickered. At one point she almost said “mail” but caught herself. Some of the conversation was lost on her, notable Irish people and current events she wasn’t familiar with. When she mentioned the taxi driver from the airport and his hot-off-the-shelf Nokia phone, the women said he was likely a gangland gangster. “A lot of the taxi drivers are now, loads of them big time into drugs and sex trafficking.” The women hooted at Margo’s shock. Throughout the night, she was careful to never sound like she was bragging. Twice, she was asked if she had kids.

Mam pushed the trolley forward and pointed to various items on the shelves, which Margo dutifully fetched. The trolley filled.

From another aisle, a woman shouted. “What did I say?” Slaps on bare skin and a child’s wail sounded.

At the meat counter, Mam ordered four beef burgers and four chicken breasts. “Better to be looking at it than looking for it.”

“Now you said it,” the butcher said, his dark head the size of a football and his apron a brilliant, deceptive white.

At the line of checkouts, the same angry woman’s voice sliced the air. “I told you to shut your mouth!” A thump followed, and the boy roared. A baby bawled.

Another woman spoke up, the stern voice of authority. “Is everything all right here?”

“She shouldn’t be allowed to have children,” Mam muttered. “Good people, on the other hand, should. Or there’ll be none of us left.”

As Margo drove out of the underground car park, Mam blessed herself. “We made it, thank God.”

Sometimes Margo ached to move back home, and other times she was glad she lived on the other side of the world.

*********

Margo and Kevin’s mother sat opposite each other inside the picture-perfect living room, in full view of the rolling fields and their scatter of cows, trees, and houses. At seventy-one, Josephine remained an attractive woman with silver hair, a dewy complexion, and sapphire eyes. It was from her, rather than his late father, that Kevin had inherited his leading man looks. She wore a green and yellow plaid shirt over baggy brown corduroys, her wedding ring hanging from a gold chain that fell below her large breasts. Margo realised Kevin’s father was dead three years already. It seemed half that length ago.

Her attention strayed to the upright wooden piano in the corner. She could almost feel its sun-soaked warmth. All these years, and she remained stunned that no one in the family could play the impressive instrument.

Josephine followed Margo’s gaze. “I keep threatening to take it up one of these days. Meanwhile, I sit at it and pretend I can play.” She chuckled. “It’s almost as good as the real thing.”

“How can you know?” Margo didn’t ask. To her mind the neglected piano made for a sad ornament.

She accepted a second, cream-filled fairy cake, knowing she wouldn’t be allowed to refuse. It was easy punishment. Josephine was an excellent baker and had given Margo many recipes over the years, but she had yet to try any of them.

“I’m a woman of leisure now. Niall and Jackie do everything about the farm, and do you think her expecting has slowed her down any? Not a bit. Niall did well there, I can tell you. As did Kevin,” Josephine quickly added.

Margo pretended not to notice the slight. She always got the feeling her in-laws liked her well enough, but that she never quite measured up. “Do you miss the farming?”

“Not for a second. I served my time,” Josephine said, laughing. She reached for the blue willow-patterned teapot and the wedding ring turned necklace dangled midair. “I’ll make us a fresh sup.”

Margo followed her mother-in-law into the kitchen. While they waited for the water to boil, Josephine gossiped about friends and neighbours who Margo either didn’t know or could barely recollect. “You remember Elsie White from the post office? She died there a few weeks back. They’re saying the kids buried her separate from the husband because at some point she had an affair. The names of plenty of suspects are flying about, but no one knows for sure. It’s killing us.”

Margo flinched. She could imagine what would be said of her, if they knew what she’d done.

Josephine nodded at the plant on the table, its pot still covered in green gift wrap. “I love orchids, thank you, they last ages.”

Margo also appreciated the plant’s resilience, and stark beauty. Plenty threw the orchid’s skeleton away, but if you tended and waited long enough, the flowers returned, more striking on each bloom.

“You couldn’t persuade Kevin to join you, obviously. I keep telling him he works too much,” Josephine said.

“December will be here before you know it.”

“This must be a very good friend of yours, that you came for her wedding?”

Margo bristled, hearing the accusation. “Yes. Brigid and I are best friends.”

At least she and Margo were best friends growing up, and had managed to stay as close as could reasonably be expected, having lived three thousand miles apart for over a decade.

*********

Back in the living room, afternoon surrendered to evening. Throughout, Josephine pressed Margo to eat and drink, and to tell her more news of her middle son. Niall and Jackie returned home from the milk shed, their dirty wellingtons left outside the back door and their stockinged feet almost the same size.

“When are you headed back?” Niall said. Every trip, it was the question people asked the most.

Jackie rubbed her baby bump with both hands. “Four weeks to go. It can’t come soon enough.”

Margo wanted to cut Jackie’s long brown hair into a shaggy bob with bangs and dye it pink-red, like rhubarb. It would open up Jackie’s face and make her hazel eyes pop.

“You and Kevin need to hurry up and get in the family way, too. I’m not going to live forever,” Josephine said, part jovial, part scolding.

Margo felt herself pitch forward toward the navy rug and blinking, inhaling, was surprised to find herself still sitting upright on the couch.

Margo’s hosts insisted she stay overnight and not attempt to drive back to Dublin. “You could fall asleep behind the wheel,” Josephine said.

Margo stuck to her plan. She was all talked and all quizzed out. The three thanked her repeatedly for visiting.

On the long drive home, the radio kept her company. She kept seeing Jackie. Even with that underwhelming hairstyle, the pregnant woman glowed.

The nine o’clock news headlined with Nelson Mandela’s upcoming visit to Croke Park, to open the Special Olympics World Summer Games. Margo had vague memories from the eighties of a small group of young, working-class women, and maybe a lone male, too, who refused to sell South African produce in a protest against apartheid and Mandela’s life imprisonment. The workers were fired from Dunnes Stores, and their resulting strike lasted years, until their jobs were finally reinstated and the Irish government banned the sale of South African goods nationwide. Margo didn’t remember particularly caring back then, but now she appreciated those young protesters’ strength and courage. To be ordinary and discounted, and to dare to stand up to that much power, it was risky, remarkable. It could crush you.

In the Event of Contact|Ethel Rohan|Dzanc Books|ISBN:9781950539260|€13.00

If you have an extract from a collection that you would like featured on Books Ireland, please contact ruth@wordwell.ie