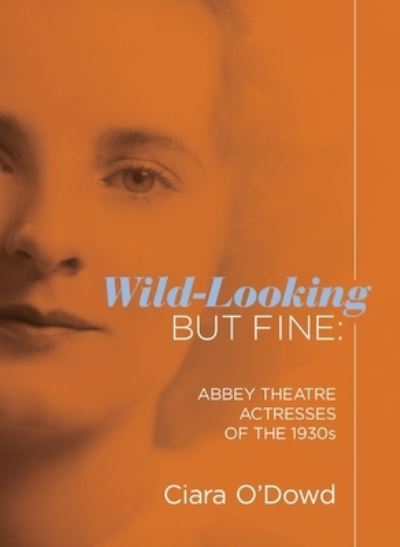

Wild-Looking but Fine: Abbey Theatre Actresses of the 1930s, by Ciara O’Dowd

In her foreword to Wild-Looking but Fine by Ciara O’Dowd (UCD Press), Jane Brennan wonders why so few biographies have been written about women in Irish theatre.

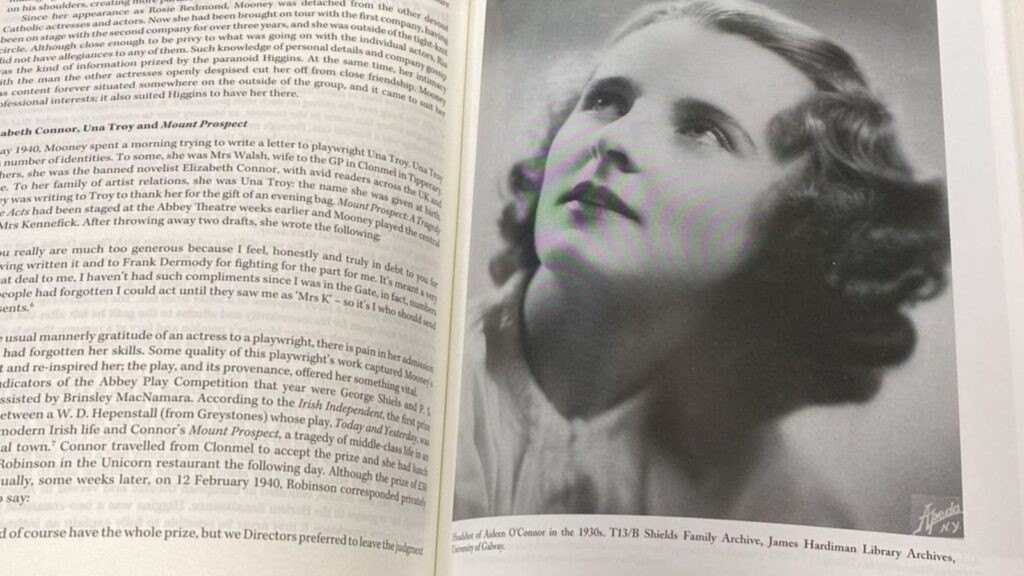

‘Why don’t we know more about their lives and achievements? Why, for example, is Ria Mooney not more widely remembered as the renaissance woman she was? Why had I never before heard of Aideen O’Connor (but am well acquainted with the name and reputation of her husband Arthur Shields)?’

This book traces the theatre careers of Mooney and O’Connor from their stage debuts to performing in New York, and the lives they made for themselves beyond the stage.

An extract from Wild-Looking but Fine, by Ciara O’Dowd

In the three years after the Irish premiere of Long Day’s Journey Into Night, Ria Mooney directed six new plays at the Abbey.

Nervous anxiety was now causing her increased spates of memory loss and she was notably weaker and openly disillusioned. Her isolation was compounded by tensions backstage: the actors were moving towards a strike, demanding more money in tandem with an improved artistic regime. The newly-established Players’ Council sought more contemporary plays with longer rehearsal periods, and some of the most influential members thought little of Mooney’s old-fashioned discipline.

There was a malicious complaint that ‘she couldn’t direct traffic’. But there was still work for Mooney to do and her sense of theatre remained impeccable.

Discovering The Enemy Within

With his usual distaste for anything slightly unconventional, in 1962 Ernest Blythe passed off to Mooney a new play entitled The Enemy Within. She had been repeatedly overlooked as a director for new productions and had chosen to bear the slights to her reputation with silent dignity. Despite her frailty, when she read the script by first-time playwright Brian Friel, Ria was captivated by the tale of St Columba and his struggle to choose between the monastic life and his home. Mooney was amongst the first to identify the talent of one of Ireland’s foremost playwrights.

Mooney was amongst the first to identify the talent of one of Ireland’s foremost playwrights.

The Enemy Within stages an imagined life of St Columba and some of his faithful followers in Iona in 587AD. With warmth and wit, it puts modern dialogue into the mouths of these mythic figures. Although it didn’t achieve the same level of popular success as Friel’s later play, Philadelphia, Here I Come, it bears the marks of a growing dramatic consciousness: fluid dialogue, compelling characters, and emotional ambition.

The action is gentle; the drama is in the conflicts between the characters. Mooney cast Ray MacAnally in the lead and assembled a strong team of male actors around him. She arrived into the 12-day rehearsal period knowing that some of those actors (such as Dowling) had little respect for her methods, but she was intent on honouring Friel’s work.

‘Ria Mooney’s vigorous direction also helps to make this play one of the most adult and interesting the Abbey has given us recently.’

Laffan, who appeared in one scene of that production, remembers Friel as a well-heeled schoolteacher with an acerbic wit, driving the entire cast around Derry in his posh new motorcar. Mooney didn’t accompany the all-male company on that tour to Friel’s hometown. Laffan also remembers the script as being ‘kind of perfect’ and the cast were deemed ‘outstanding’ by critics. Although he felt the play had weaknesses, the Irish Press critic was adamant on 7 August 1962: ‘Ria Mooney’s vigorous direction also helps to make this play one of the most adult and interesting the Abbey has given us recently.’ ‘Adult’ and ‘interesting’ were features that drew Mooney to plays.

The final production she directed at the Abbey in 1963, Copperfaced Jack by John O’Donovan, was plagued by rows about unauthorised script changes and a general disrespect for the author that smacks of Blythe rather than the ever-courteous Mooney. Hugh Hunt claims she had a nervous breakdown; it’s not clear how he adduced this, there is no behaviour or evidence to support it. At age 60, Mooney resigned from her position of Director of Plays in English, when her ‘way at last became clear’. This carefully chosen phrase conceals the truth, but personal friends believe that Mooney finally retired only when she had secured money from an old friend in America to support herself.

Mooney now lived alone in Goatstown, infirm and increasingly reclusive. Having awoken from ‘the nightmare’ of her last few years at the Abbey, she spent time writing her memoirs. Sporadically, she attended the theatre, where she was amused by the huge number of production staff listed in the programmes. The Abbey’s new building she thought: ‘functional—and quite without character’.

friends believe that Mooney finally retired only when she had secured money from an old friend in America to support herself

All her life, the theatre was Mooney’s home; now it offered no solace. In fact, nothing did. In July 1969, she wrote to Mary O’Malley of the Lyric Theatre in Belfast, telling her of the death of Mrs Kick Erlanger. She told her, ‘I don’t know what I would have done without my friend in America.’ Grief-stricken, Mooney wrote to O’Malley: ‘I have lost all desire ever to take part in any performance, in any capacity.’

Old friends and colleagues did their best to help, but her health deteriorated rapidly and Ria Mooney died on 3 January 1973. She left behind her memoirs, completed but unpublished.