Never say “you never,” never say “you always”—Seán Carlson pays tribute to the magnetic Malachy McCourt

by Seán Carlson

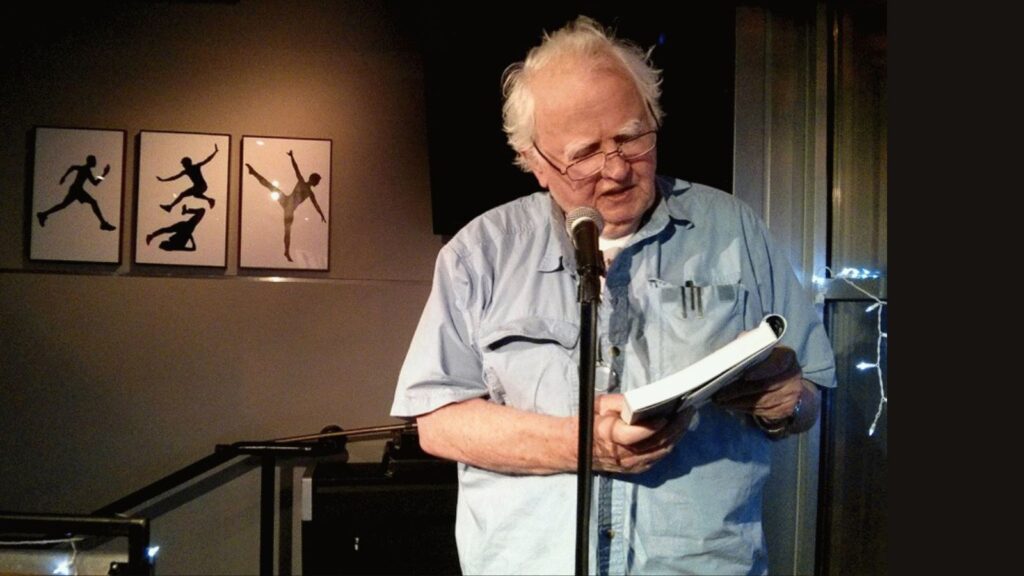

As an unhappy crowd of quiz-night patrons waited for a belated lineup of poets, playwrights, and other aspirant writers to clear out from a brightly lit bar on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in January 2016, Malachy McCourt claimed the microphone to quell the discontent. Drawing the monthly New York literary salon organised by the Irish American Writers & Artists to a close, Malachy’s voice commandeered the room as he broke into a rendition of the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem. With sincerity strengthened by humour, he led his companions in chorus:

Isn’t it grand boys, to be bloody well dead?

Let’s not have a sniffle, let’s have a bloody good cry.

And always remember the longer you live, the sooner you bloody well die.

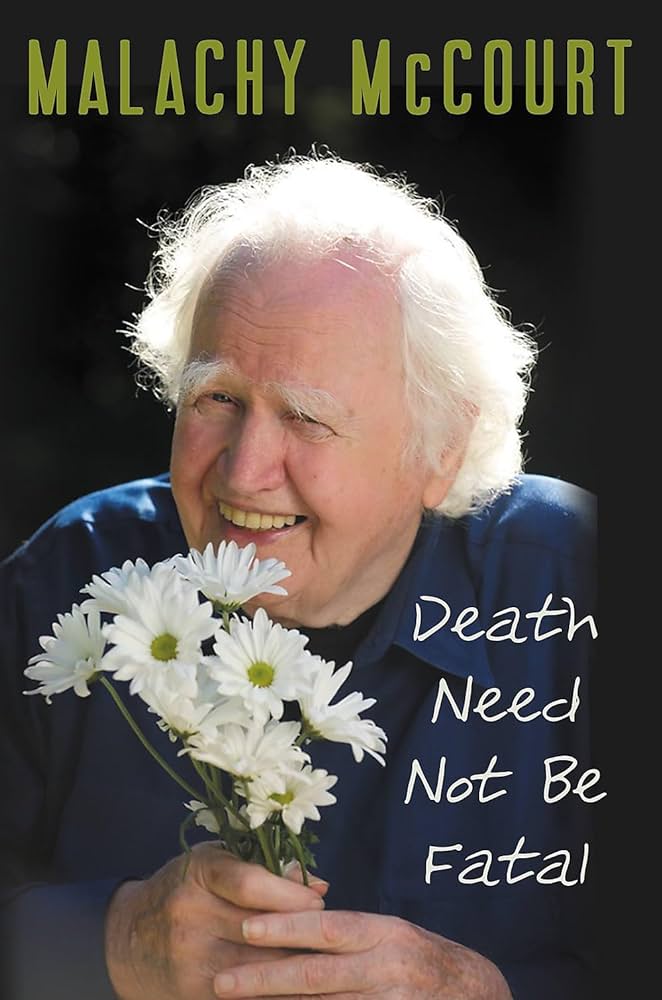

Perhaps unsurprising for a man who wrote a memoir titled Death Need Not Be Fatal, it often felt like every interaction with Malachy over the past decade involved an acknowledgement of mortality — except on his lips there was no touch of the macabre, only a proclamation of life. At his 2017 book launch, Malachy declared what a gift it was to be alive to hear his own wake. “Live every day as if it’s your last,” he said with the repetition of prayer, “and one day you’ll be right.”

While others will reminisce about Malachy’s days as a raconteur, his sharp wit and unapologetic politics, the endless nights and crowds at the Bells of Hell, the bar he owned on West 13th Street, the only thing I knew about Malachy when we first met in 2014 was his relation to Frank, whom I had met briefly at a literary festival several years earlier but didn’t know beyond his writing. Based on book sales, at least 10 million people shared a comparable degree of familiarity. As a result, Malachy held a strange duality in my mind: a man whose life seemed to be known by nearly everybody in New York and a child preserved in Ireland through somebody else’s book.

“For days Malachy’s tongue is swollen and he can hardly make a sound never mind talk,” Frank introduced his brother in the opening chapter of Angela’s Ashes, both his pain and joy. “When he laughs you can see how white and small and pretty his teeth are and you can see his eyes shine.”

When I first stepped into the cell theatre in Chelsea after finishing up work for the night a few blocks further south, I discovered Malachy at the centre of a community of other writers, actors, and musicians. He took to the floor in khakis and a sports coat and, seemingly without preparation, rifled through an assemblage of story, quip, and song that unwound from memory. His laughter echoed across his audience. His eyes shone, and he sure knew how to make a sound.

Over the following months, as our paths crossed in the city’s literary and Irish American circles, I grew to know Malachy as someone who revelled in the relationships that surrounded him. When the Manhattan Borough President declared 17 October 2016 as Malachy McCourt Appreciation Day, she feted his “ingenuity, creativity, resiliency, compassion, humor, tolerance, and love of community.” He displayed a certain magnetism that attracted others to him.

I often return to the marriage advice he offered when I shared news of my engagement: never say “you never,” never say “you always.” He had failed once before, he said, but remained grateful each and every day for a second chance in life with his wife Diana. Along the way, he had learned the secret strength of avoiding adverbs when in disagreement as well as in writing. As my wife and I had children, Malachy cheered: “Let’s make the world great for our little ones.”

When the Irish American Writers & Artists honored Malachy with its annual Eugene O’Neill Lifetime Achievement Award in 2016, well before he entered hospice care and found himself kicked out for not dying quickly enough, as he recounted in a New York Times interview last year, he resisted leaving even though the event had ended. Instead, as the venue staff began to fold their chairs and clear the tables for the night, Malachy continued to hold court off to the side of the ballroom and began to sing “Wild Mountain Thyme,” as he so often did. Malachy stood amidst friends, each calling for more. “Sing the song, children,” he summoned, his hands conducting at his sides. The verses yielded to a rousing final chorus: “Will you go, lassie, go?”

“Live every day as if it’s your last,” he said again before going—knowing one day he would be right.

Seán Carlson served on the board of directors of the nonprofit Irish American Writers and Artists from 2016 to 2020. His essays and poetry have appeared or are forthcoming in The Honest Ulsterman, The Irish Times, New England Review, Oxford Review of Books, Trasna, and elsewhere. He is working on his first book, a family memoir of migration.