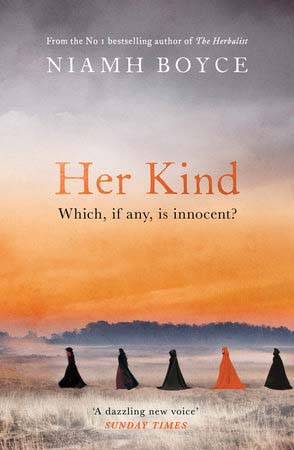

Battle of the sexes

Her Kind. Niamh Boyce. Penguin Ireland; 319pp; £12.99; 24cm; 978-1-844-88433-9.

The year is 1324, the setting is Kilkenny, the story is as old as time yet as recent as yesterday—because it concerns those who exercise power and those who are powerless. Seven hundred years on, the notorious Kilkenny witchcraft trial continues to hold our interest. Niamh Boyce is the latest writer to turn her attention to this intriguing story, giving voice in her version to one of the many silenced women in Irish history. Hers is an account of Petronelle, servant to Dame Alice Kytler or Kyteler, about whom we know next to nothing, except that she was burned alive on charges of witchcraft and heresy. The plot of Her Kind gives Petronelle a well fleshed-out backstory and imagines her life leading up to the court case. Traditionally, witchcraft was regarded as a relatively minor offence in Ireland, which staged few such trials compared with other European countries. But in this instance, sorcery was bracketed with sacrilege and the full severity of the law unleashed.

The case was significant in the history of witchcraft as the first in either Ireland or Britain where a defendant was accused of having sex with a demon, something that would become a feature of later trials. Dame Alice was said to have lain with an incubus and Petronelle was imprisoned as her accomplice in conjuring up demons. It was, of course, a clash between rival ecclesiastical and secular powers—with a number of unlucky women squeezed in the middle. This, then, is the promising raw material for Boyce’s novel.

In the novel, as in real life, Kilkenny has a zealot prelate, the Bishop of Ossory, who claims his diocese is a nest of devil worshippers. He points the finger at Dame Alice, a wealthy merchant, property owner and moneylender. The dame is a woman with an unusual amount of power. She has inherited considerable wealth from her father (she is the descendant of Flemish merchants who settled in the area), has buried three husbands and is suspected of poisoning her current husband, number four. But no matter how influential a woman may be, cry witchcraft and she becomes vulnerable.

With friends in high places, Dame Alice manages to flee with Petronelle’s daughter, either to England or Flanders. But her maid is held fast. Petronelle is the figure of central interest in Boyce’s novel and her voice is a memorable one. Yet while the novel has tension and pace, oddly the question of witchcraft is only raised halfway through.

Dame Alice, although she is a nuanced character, is never quite likable but always sure of what she wants. It would have been easy for the author to make her sympathetic, the misogynistic focus of suspicion and envy, but she has the confidence to show the dame, warts and all, as a woman of unapologetic drive. She is no plaster saint, even if she does instruct an artist to paint her face onto a mural of the Virgin Mary.

We know from the historical record that Petronelle and some associated women were accused of heresy, including misusing churches and making sacrifices to demons. The others were released, however, and only Petronelle was condemned to a horrifying death. Another protagonist is the humbly born and equally ambitious Richard de Ledrede, a Londoner who is French-trained in clerical law and ends up in Kilkenny as Bishop of Ossory. Like Dame Alice and Petronelle, he was a real character, although his voice is more familiar to historians because he wrote his own account of events surrounding the trial. The bishop is the unmistakable villain of the novel, a man who sees diabolical deeds wherever there are uppity women—and even where the women are humble. He seems to believe the entrepreneurial Dame Alice is a threat to Church power, conflating menace with her sexuality.

In his retelling of Petronelle’s confession, he writes: ‘by the crossroads outside the city, she had made an offering of three cocks to a certain demon whom she called Robert, son of Art, from the depths of the underworld. She had poured out the cocks’ blood, cut the animals into pieces and mixed the intestines with spiders and other black worms like scorpions, with a herb called milfoil as well as with other herbs and horrible worms. She had boiled this mixture in a pot with the brains and clothes of a boy who had died without baptism and with the head of a robber who had been decapitated …”

Apparently, Petronelle also described a demon having intercourse with her mistress while she watched—the first recorded case of such a claim. It is lurid stuff and one wonders why Petronelle made such a confession and whether she was promised her freedom in return for such a flight of fancy. We know she was tortured and whipped, no doubt motive enough, although Boyce never offers a compelling reason for the vividness of confession. Perhaps the bishop helped her along. Towards the end of Bishop Ledrede’s eventful life, the Archbishop of York drafted a letter to the Pope asking for his removal, accusing him of madness and persecuting his parishioners. Clearly, he persecuted poor Petronelle—and would have made short work of Dame Alice, given the chance.

In an interview for RTÉ’s ‘Arena’, Boyce tells of contemporary accounts referring to Dame Alice’s red hair and considerable charm—which the bishop regarded as evil and linked with witchcraft. But it is worth noting that the real Ledrede was a fiery character with a taste for confrontation, and not without personal courage when imprisoned himself. It seems a pity to reduce him to a cardboard cut-out. Elsewhere, an anchoress, or holy woman, who is walled up to die of starvation in St Canice’s Cathedral is a character worth a novel in her own right. Maybe next time.

Boyce, who won Newcomer of the Year at the Irish Book Awards for her first novel The Herbalist, has once again carried out painstaking research. Kilkenny is lovingly evoked, from its laneways to St Canice’s and the castle. We learn it was a segregated place with a walled, English part of town, and an area beyond this where the ‘mere’ or ‘wild’ Irish lived in bogs, mountains and rocky caves like wild animals. Boyce gives us a flavour of two societies straining against each other, one stratified and the other tribal. She maintains control over her material and never allows the historical detail to overwhelm. But perhaps she fumbles her storytelling once or twice; for example, when the maid is tied to the stake for public execution—an appalling death that is glossed over. This is, after all, one of the few facts we know about Petronelle and it must have been as terrifying as it was agonising.

Today, Kilkenny is proud of its dramatic witchcraft trial and Kyteler’s Inn, once owned by Dame Alice, is a tourist attraction. It is impossible to visit the area without hearing about her—Petronelle’s name lags well behind. In artistic terms, the path to Dame Alice and her victimised maid is a well-trodden one. In recent times, there was both a novel and musical, while a short story in Emma Donoghue’s collection The Woman Who Gave Birth to Rabbits imagines Dame Alice as immortal, walking Kilkenny’s streets in search of some remnant of Petronelle.

Umberto Eco mentions the case in The Name of the Rose and even W.B. Yeats references ‘the love-lorn Lady Kyteler’ and the sacrifice of ‘red combs of her cocks’ in his poem ‘Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen’. Feminist artist Judy Chicago set a place for Petronelle at‘The Dinner Party’, an installation piece of 39 mythical and historical women on permanent exhibition at New York’s Brooklyn Museum. So, not forgotten, those sensational events in Kilkenny of 1324, including Petronelle’s unfortunate fate to be sacrificed by a bishop thwarted of his intended target. Both women—the one who escaped and the one who died in her place—remain a source of inspiration. Such stories bear retelling.

Martina Devlin is the author of the novel The House Where It Happened (Poolbeg) about the Islandmagee witch trial of 1711. Her latest book is Truth & Dare: short stories about women who shaped Ireland. (Poolbeg).

(First published in Books Ireland magazine July/Aug 2019)