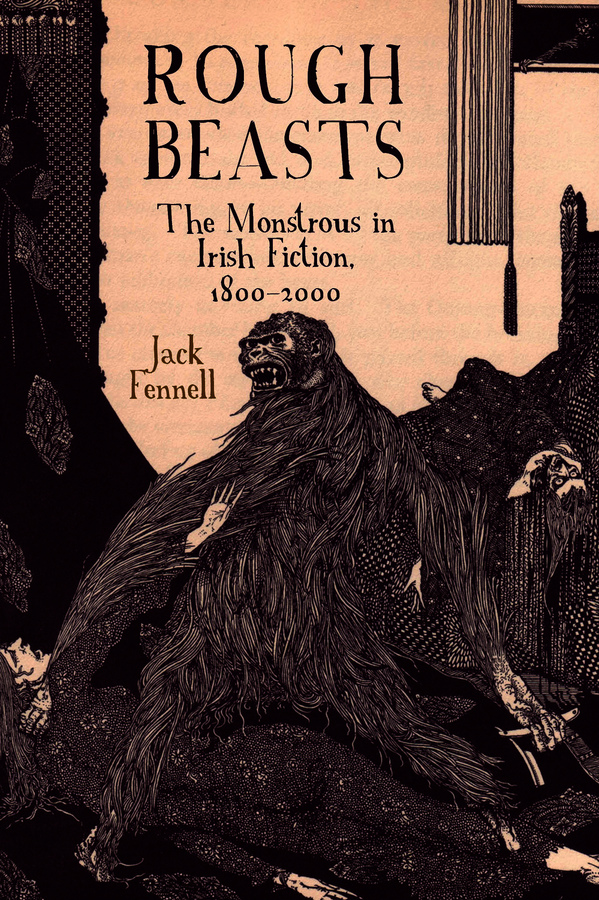

Rough Beasts

The Monstrous in Irish Fiction, 1800-2000

by Jack Fennell

£90 HB | 9781789620344 | 296 pp | Liverpool University Press| 31/01/2020

We seem to think that we are now living in an age of monsters – and I don’t mean those who exist only on the page or screen. Even a brief jaunt into the world of social media brings you into contact with an incredible cast of improbable characters, who all hate each other and spend much of their virtual time hurling abuse and describing their ‘opponents’ in terms that seem taken directly from the horror genre. It’s something of a relief, then, to be reminded that ’twas always thus. There have always been monsters, lots of them. In Jack Fennell’s new study of the ‘monstrous in Irish Fiction’, the reader is given a guided tour of the Irish horror landscape, populated by malevolent fairies, witches, ghosts, zombies, vampires, werewolves, demons, and a multitude of other creatures you wouldn’t like to encounter, demonstrating that an interest in (or an obsession with) the monstrous has been close to the surface of Irish culture for centuries. Indeed, defining the monster as a ‘supernatural antagonist’, as Fennell does in a terminology-clearing Introduction, actually leaves out the very human killers, torturers, sadists that some of us might be inclined to consider monstrous too.

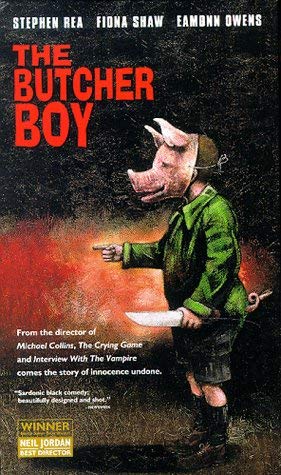

It is notable, for example, that one of the great Irish horror novels of my own lifetime, Patrick McCabe’s The Butcher Boy (1992), finds no place here, though I wager that many find Francis Brady even more frightening than a Count Dracula. Moreover, describing even some of the monsters surveyed here as ‘supernatural’ might be a stretch: while Carmilla’s proclivity for the blood of virgins certainly makes her antagonistic, the character herself has not much time for the supernatural, scoffing like an enlightened sceptic at the suggestion that everything is in the safe hands of God, insisting instead that ‘All things proceed from Nature – don’t they?…I think so’. Perhaps Carmilla doesn’t really understand her own nature, but she might be better thought of as a biological mutation than as an agent of a supernatural power, more like a giant cockroach than a demon lover, which would also go some way to explaining all the references to organic transformation in the story. Ghosts, too, particularly in their Victorian and Edwardian manifestations, were often considered paranormal rather than supernatural (indeed, the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) expended a great deal of energy attempting to convince everyone that if ghosts did exist they were natural phenomena).

Disagreement about terminology, though, is characteristic of the scholarly discussion of Irish gothic and horror, and monster theory is a hotbed of disputation and hair-splitting, as the Introduction ably reveals, and therefore it is hardly surprising that I found much to disagree with here, from the readings provided of some of the central texts, to the very interesting and original argument that holds much of the material together. Fennell sets up this analysis of horror as a sequel to his ground-breaking study of Irish Science Fiction (2014), and the middle child of a trilogy that will eventually conclude with a study of Irish fantasy. He argues that all three of these non-realist genres are characterised by a particular attitude to history: ‘fantasy ignores accepted history, science fiction pretends that it is history, and horror ends history’, with the horror monster being ‘the one who actually does the history-ending work’. Such a description of horror’s relation to history is certainly challenging in that, as Fennel notes, it opposes much historicist work in Gothic and Horror Studies, and while I remain unconvinced, and think the textual evidence supports the historicist case much better and that horror and the Gothic is more about the impossibility of escaping from history than bringing it to a dramatic conclusion, this was certainly a stimulating counter-argument.

What is most impressive about this book is the sheer range of theoretical and fictional material with which it engages. Fennell considers monster theory, folklore, evolutionary psychology, historiography, affect studies, phenomenology, as well as an extraordinary number of novels and short stories in both English and Irish, many of which I had never even heard of before, thus supplying the reader with a very enticing reading list. It is a very welcome addition to the growing scholarship on Irish horror fiction.

Jarlath Killeen is a lecturer in Victorian literature at the School of English, Trinity College Dublin, and current Head of School.

Out now from Liverpool University Press.