Dublin: One City, One Book—a moving story of growing up in the 1960s and 1970s

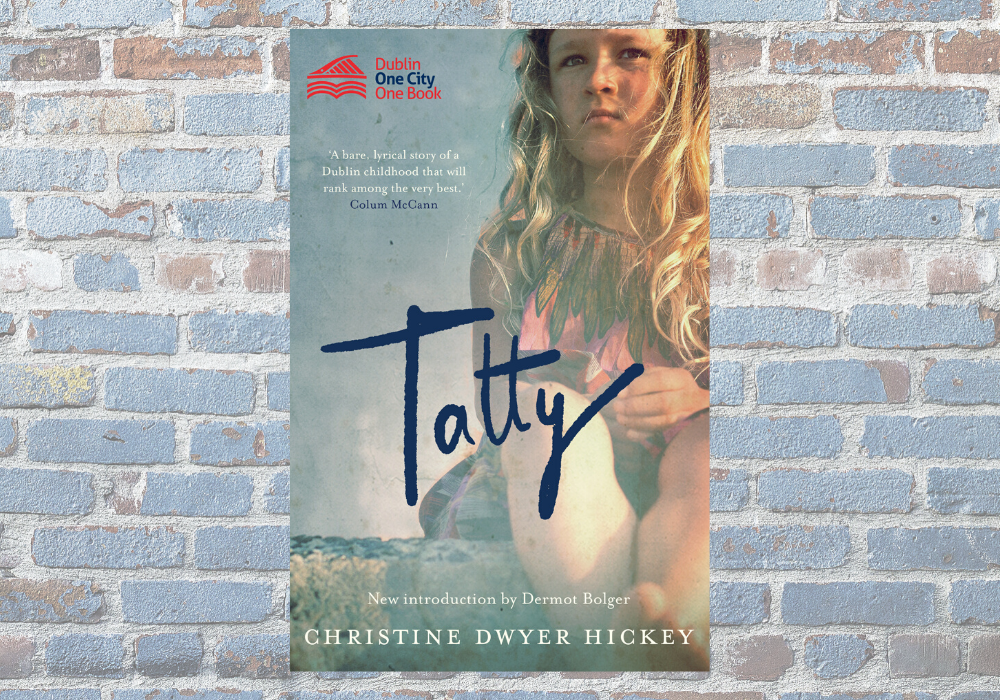

Tatty.

by Christine Dwyer Hickey | New Island | 208pp | €11.95 pb | 9781848407619.

Tatty was first published in 2004 to great acclaim. Now it has been chosen as the 2020 Dublin: One City, One Book and republished with a new introduction by Dermot Bolger. Part memoir, part novel, it tells the story of a Dublin girl growing up within a troubled, alcoholic family in the 1960s and 1970s.

In his introduction, Bolger acknowledges that ‘no voice is harder to catch than that of a child’. The task comes laden with complications around how to achieve a convincing voice and how to render the child’s contact with an adult world she cannot always understand. Dwyer Hickey achieves all of this in a deceptively simple story. Tatty’s perception develops with each of the ten chapters as she grows from an innocent four-year-old to a bright teenager of fourteen who begins to understand what is happening all around her.

The novel is mildly experimental in its narrative format. Tatty never uses the word ‘I’ and her telling alternates between second- and third-person narrative with dialogue blended in seamlessly. This could easily result in distancing the child from the reader and preventing total empathy with her plight, but the authenticity of the telling is so convincing that we never doubt her word, and her voice rings true throughout.

Despite its traumatic family situation, there is lots of humour in Tatty’s story. Overheard fragments of conversations and children echoing adult speech lead to many comic moments. Many of them remind me of Paddy’s observations in Roddy Doyle’s Paddy Clarke, Ha Ha Ha. While Doyle ventures into social commentary in his novel, however, Dwyer Hickey does not. This is Tatty’s story: there are no tangents and the larger world without never impedes the localised world in which Tatty exists. The book captures Dublin in the 1960s and 1970s very well. It is peppered with brands we can relate to—Perri crisps, Cinzano Bianco, Dubonnet, milk decanted into an empty cough bottle for lunch.

The family are not impoverished and there is no absentee alcoholic father here. Tatty is happy a lot of the time, travelling around with her dad and getting her own tiny glass of Guinness (which tasted like ‘black Buttermilk’), being told she is great for going across to the bookies all by herself. The pathos is evoked from the sheer bad parenting, the cruelty of the comments from her aunts and her mother, and the way Tatty learns at a young age that being in her family involves keeping secrets and lying where necessary to school friends and nosy neighbours. She and her older sister throw away their lunch milk because it is given to them in a Baby Power whiskey bottle and the older sister knows this will label them as a ‘family with a drunk’.

The mother’s voice is largely absent from the story and we do not know what she endures as the wife of ‘Dad’. The child provides glimpses of her mother’s life, such as her visit to the school to try and persuade them to accept her child with special needs. Her dread of that child attending ‘an institution’ similar to the one her brother spends his life in. The terrible stigma attached to mental illness, which is used as an insult hurled during a vicious row. Those circumstances were most likely the cause of her dependence on alcohol rather than the father’s accusation to the children that: ‘you lot drove her to it … What she has to put up with from you lot’. A single chapter from the mother’s point of view would have been electric.

There are no judgements or overdramatising of events in Tatty’s story. The novel ends in a suspended moment. A modestly optimistic interpretation would be that Tatty and her sister have observed enough varied possibilities to realise a different life from their mother’s. Their dad outlines big changes for the household but, as he does not include his own behaviour in the grand plan, the reader is left in doubt.

Anne O’Leary

Anne would describe herself as a literary ‘odd-job woman’ and loves working with words.