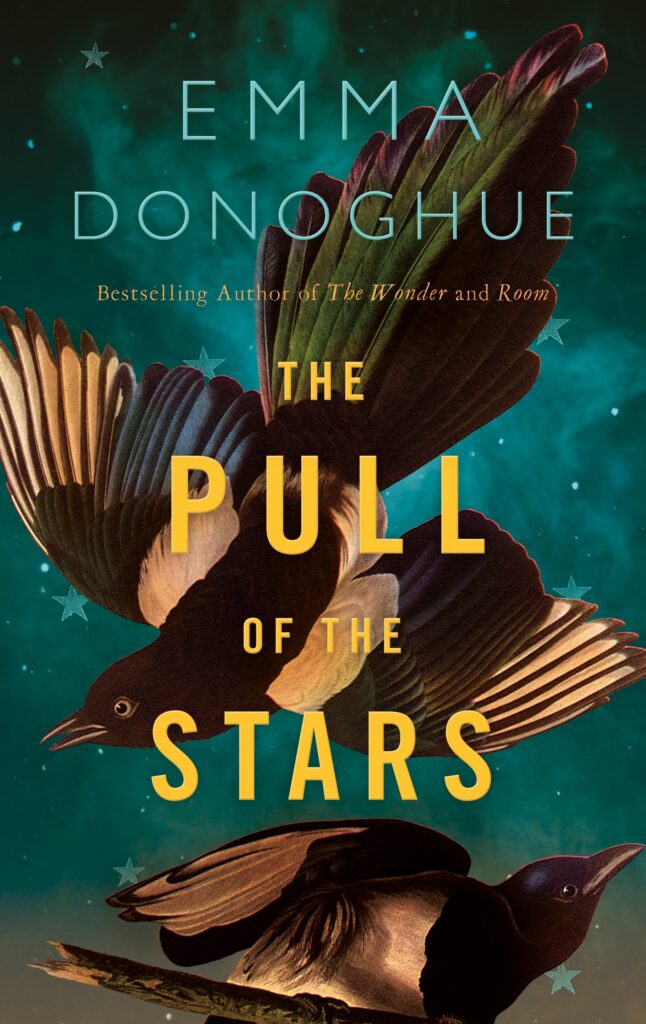

The Pull of the Stars

by Emma Donoghue | Picador Books | €14.99 pb | 256pp | 9781529046168

review by Laura King

The Pull of the Stars is an incredibly consuming and beautifully written new novel set over three days in a fever ward during the 1918 Great Flu epidemic in Dublin. When we meet practical, responsible Nurse Julia Power, she has left home—where she cares for a shellshocked brother, home from the battlefield—and is travelling in to work in a maternity fever ward in Dublin city centre, after deciding to give up her days off to help her patients. This decision to work these three seemingly insignificant days sets in motion the events of the novel and changes everything for Julia, as her world narrows down to what happens within a cramped maternity fever ward and she is forced to step up into a position of power. As we read on, Julia goes from being the careful, obedient nurse she was trained to be to having to hold down a ward by herself, trusting her own instincts and fighting for the patients everyone is too busy to care about, and dealing with the emotional burden of her job and the shock of the secrets of the people she meets. More than anything else, Donoghue shows us how all rules and power systems are suspended in times of war and crisis, and that through all this chaos and death there is a possibility of rebirth.

It seems impossible to think that Emma Donoghue finished this novel before COVID-19 was declared an international pandemic—what uncanny timing. When I read this novel just as restrictions were being eased in Ireland, I felt that the Dublin I live in didn’t feel drastically different to Julia’s Dublin. In The Pull of the Stars, it is 1918, and the city and its people are marked by three major events: the recent yet devastating flu epidemic, the ongoing First World War, and the aftershocks of the 1916 Rising. Dublin, as Julia passes through it, is visibly marked by all three events, from the makeshift war memorial strewn with flowers for the Irish men fighting for England, posters instructing passers-by how to prevent the spread of the flu, and closed businesses and damage done to General Post Office and its surroundings. Donoghue’s Dublin is a vivid and war-torn landscape, and the hospital feels like a bulwark against the destruction of the city itself. As the novel goes on, however, we feel increasingly that nowhere is really safe, and the hospital and its staff are at breaking point. The destabilisation of the power system within the hospital, where the matron and the male doctors rule all, facilitates the expansion of Julia’s world view.

Julia is already well aware of how class affects the lives of her patients, especially the mothers on their twelfth pregnancies despite complications with earlier births. She knows about the trouble that rich and poor women can have with abusive families, and throughout the course of the book she becomes all too aware of the evils that happen behind the closed doors of Church institutions. The theme of systemic cruelty and abuse runs throughout the book and this plays out in the hospital, perpetuated by people in positions of power, such as the cold and judgemental ward sisters and the male doctors, who are absent at best and negligent at worst—allowing their own egos to colour their judgement and their preference for procedures that will allow women to have more children rather than lessening the pain or improving their quality of life. She is forced to challenge her prejudices and certainty that she knows best when she is forced to take responsibility for her patients, and when she meets the two other women who she comes to rely on. Bridie, an innocent-seeming but capable young woman who volunteers as a runner, and Dr Kathleen Lynn, a revolutionary and underestimated female doctor, shatter Julia’s preconceptions about power, knowledge, gender roles and sexuality.

Her friendship with Bridie quickly develops through their dependence on one another, and the two women realise the depths of their feelings as Bridie tells Julia about her life as a boarder with the nuns and her traumatic childhood growing up shunted from institution to institution. This is possibly the most striking part of the book; before this, Julia was telling Bridie ‘obvious’ things about the body and the world, but the reader sees in real time how all the things that Julia feels she knows about life, as a worldly nurse, feel no longer true, and her world view is changed forever.

This is an incredibly engaging book, and after hooking me with a great story and compelling characters, made me think differently about that political moment in history—how the epidemic was managed by the government, how the poor were (and are) disproportionately affected and how women throughout history have had to fight, not always in the battlefield, but in hospitals and in the home, and how people have struggled for years while being trapped in institutions. I felt deeply sad after finishing, as this is just one story of so many; these problems are not safely in the past, but must be faced, bravely, every day. In a pivotal moment in the book, Julia tells Bridie that the world influenza comes from Renaissance Italy, when people used to believe that the influence or ‘pull’ of the stars was what made them ill. Certainly, in a world where everything has changed and no one can explain why, fate feels just as likely as anything else, and Julia and Bridie’s meeting feels like fate. Dr Lynn says that eventually humankind will come to a ‘stalemate’ with the virus and we will live alongside it. It is perhaps a comfort to know that this has happened before and we have got through it. While the novel is upsetting in places, it shows us that there are unprecedented moments throughout history, but they, too, can pass, and humankind has survived so much—we will survive this too.

***

Laura King works in publishing in Dublin, and in her spare time reviews books online under the name @lauraeatsbooks