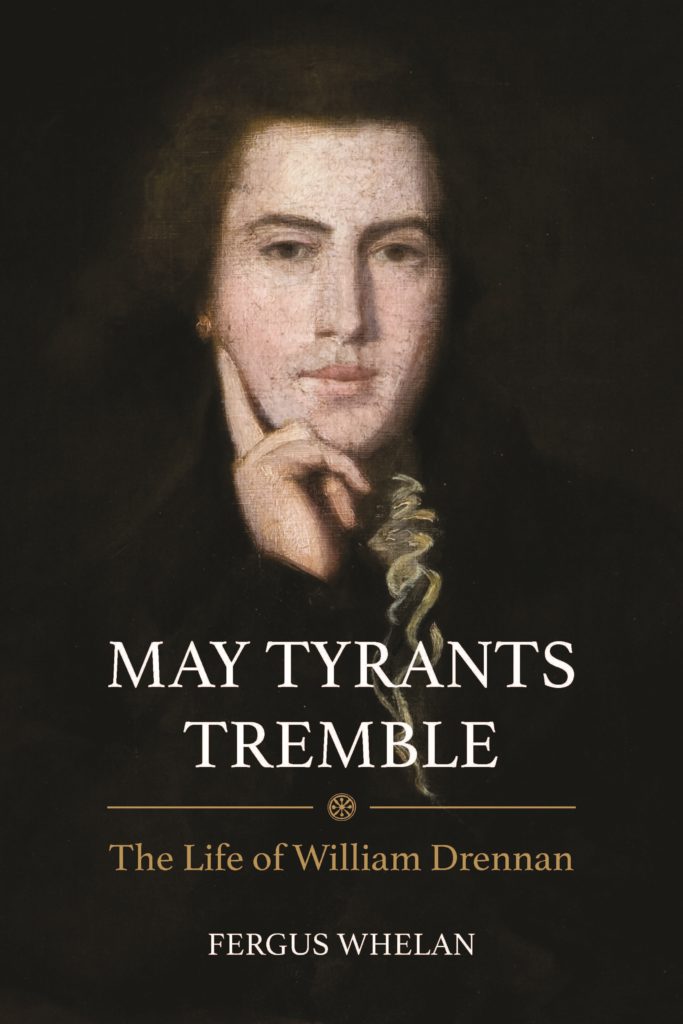

May Tyrants Tremble:

The life of William Drennan, 1754–1820.

By Fergus Whelan | Irish Academic Press| 351pp| €29.95 pb | 9781788551212.

Review by Tony Canavan

Champion of the Emerald Isle

A modern biography of William Drennan is welcome, for he was that rare thing in Ireland, a truly ideological republican, who believed in the sovereignty of the people and praised the execution of kings. If that makes him sound like a single-minded fanatic, you would be wrong to think so. As Whelan illustrates in this excellent biography, Drennan’s political thinking was complex and he employed sophisticated arguments in his attempts to reconcile religious and political divisions in Ireland. As an aside, Drennan is worth remembering for devising the Society of United Irishmen, and for coining the phrase ‘Emerald Isle’.

I lectured on Drennan at Queen’s University and got to know him well while researching my history of Newry, where he lived for some time. Drennan must be a gift to a biographer, as he wrote copiously: letters to his sister Martha and friends, addresses to public figures and pamphlets and other writing. This makes it comparatively easy to follow Drennan’s life, public and private, and Whelan does a good job of balancing the personal story with the political.

To a modern reader, the intricacies of religious and political controversies in the late eighteenth century can appear arcane, but Whelan explains the background and context of the various issues, such as New Light Presbyterianism or the difference between Whiggism and republicanism. Likewise, he explains the significance of many of the individuals in Drennan’s life.

Drennan’s significance is underplayed by many historians and he is often dismissed as narrow-minded or even an anti-Catholic bigot. A major objective in this biography is to rehabilitate Drennan’s reputation. This is a worthy enterprise as Drennan played a considerable role in developing the political ideology of radicals from the heyday of the Volunteers to the United Irishmen. His open letters and addresses coherently and persuasively argued the case for the union of Irishmen, civil rights for Catholics and, ultimately, an Irish republic. Drennan influenced those around him and laid the foundations of republican politics to this day.

While I largely agree with Whelan’s position, I think that sometimes he overstates his case. Throughout this book he addresses the charge that Drennan was anti-Catholic. It is true that prior to the French Revolution, like many Protestants and Presbyterians, Drennan thought Irish Catholics not civically developed enough to be admitted as citizens. As Whelan points out, he did change his mind and became an advocate for Catholic emancipation and welcomed them as fellow revolutionaries. Despite this, however, the evidence cited by Whelan would indicate that Drennan still had problems with Catholics. He complained more than once that Catholics would not support his medical practice and often warned his companions against trusting Catholics, even members of the United Irishmen.

On the subject of Drennan’s trial, Whelan argues that it made no difference to his commitment to the cause, but, again, his own evidence would indicate otherwise. Although he was acquitted, Drennan continually expressed the fear that he would be arrested again and gave this as the reason for not participating in certain meetings or writing for some time. That Drennan was excluded when the United Irishmen went underground and took no part in the 1798 Rebellion would indicate that he had distanced himself from revolutionary action.

I think, too, that Whelan might have been more sceptical about Drennan. He accepts at face value Drennan’s assessment of his own importance. If the government had really seen him as a threat, they would have ensured his conviction at his trial for sedition. Both before and after 1798, friends of Drennan were forced into exile, arrested and even hanged while he walked the streets freely. It would seem that the authorities viewed him as a minor threat but no real danger.

In 1807 Drennan returned to Belfast and Whelan does a service by highlighting the many good works that he was involved in there. He may have stepped aside from politics but he was an exemplary citizen. He helped to establish or develop such things as the Belfast Society for Promoting Knowledge, the Historic Society, and the Friends of Civil and Religious Liberty. His crowning achievement was the establishment of the Belfast Academical Institution, a pioneering secondary school that still exists today.

This is a worthy biography of someone who was a key figure in late-eighteenth-century Ireland and whose legacy has been overshadowed by that of some of his contemporaries and disputes over aspects of his politics. Whelan has done a good job in restoring Drennan to his rightful place as a prime mover in the United Irishmen and establishing republicanism in Ireland. He also, however, paints a full portrait of the man and draws attention to his other achievements.

***

Tony Canavan