Mary McCarthy talks to Ronan Sheehan, Editor of Cuban Love Songs (Cassandra Voices)

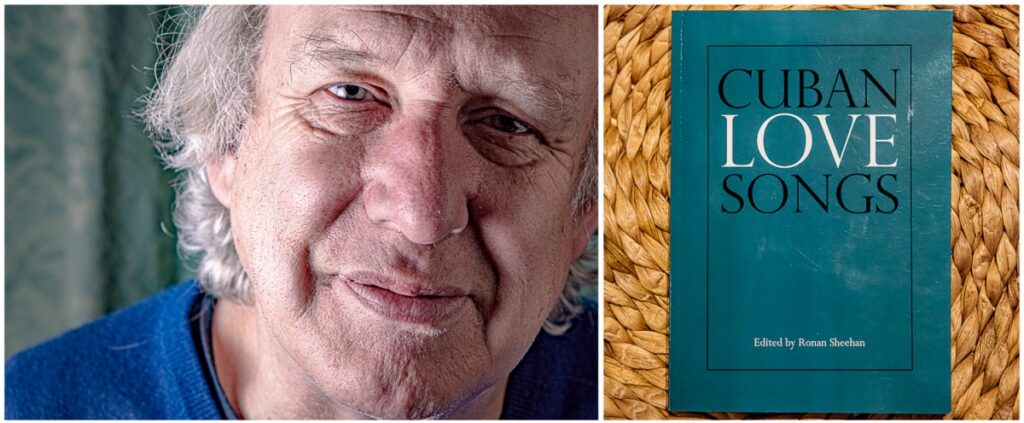

Cuban Love Songs is a gorgeous collection of fifty poems translated by Irish writers and edited by the well known writer, Ronan Sheehan.

It is a project that took two decades and an immense effort went into it.

Ten years ago Ronan did a translation of the Latin poet Catullus called ‘The Irish Catullus or One Gentleman of Verona’ so he knows the tools required and he selected his translators on the basis of them having a way with words – they did not have to be poets – although there are many well established poets here – they just had to know how to arrange words to make them sing.

When Ronan was introduced to Latin American literature in the 1970s by his good friend Neil Jordan he got hooked on Cuban writers; his favourite book was the 1949 historical novel of the Haitian slave revolt, The Kingdom of This World by the writer Alejo Carpentier.

Cuban Love Songs is jointly dedicated to Carpentier, along with John Philpot Curran – an Irish barrister and poet, and a relative of Sheehan on his mother’s side. Both opposed slavery.

In 1982 Ronan edited an issue of literary magazine The Crane Bag on Ireland and Latin America and he regretted not having showcased any writing from Cuba.

When he was appointed to the board of Poetry Ireland, and the possibility of going to Cuba came up, he seized his second chance.

His friend Eamonn Connelly had a brother Niall living in Havana, and he introduced Ronan to the Unión Nacional de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba, (UNEAC).

Niall made the approach to the writers union and in December 2000 the plan was hatched to create a joint anthropology of poetry.

It’s a romantic story and the pictures in the book conjure up the fun and romance of Cuba – even if we cannot visit, this book will give you a delicious taste in lockdown.

Another Irish connection is the title, which comes from a Flann O’Brien quote from At Swim Two Birds.

“They sang love-songs and moon sweet madrigals and selections from the best and finest of Italian operas.”

When I interviewed Ronan he pointed out a book is not just words, but rather it is a physical object and he was determined this would be the case with Cuban Love Songs – that it would be an attractive book people will be drawn to.

There is a sadness to this project. When you have such a big time lag with a project there is going to be loss of some of the players involved – this is the cruel nature of life.

The first designer James O’Nolan tragically died (in 2018 from injuries sustained while cycling in inner-city Dublin) and this is when Kate Horgan (Bespoke books) came on board who did a superb job.

Two of the translators also passed away before publication : Philip Casey, novelist and poet, and Gerard Lyne, poet and keeper of manuscripts at the National Library of Ireland, who died in January 2019.

Seamus Heaney once spoke of “the kinds of truth art gives us many, many times are small truths. They don’t have the resonance of an encyclical from the Pope stating an eternal truth, but they partake of the quality of eternity. There is a sort of timeless delight in them.”

The ‘small truths’ are everywhere here in poems such as ‘The Man you were meant to be waiting for you now’ (‘Da Capo VI’ by Raul Hernandez Novas) translated by Dylan Brennan – how life rarely turns out as predicted.

‘Faithful Tournament’ translated by Grace Wells (Torneo fiel by Anton Arrufat) describes how a constantly warring couple can still be in love.

‘They Write Love Letters’ translated by Marion Kelly is beautifully done (Reina Maria Rodriguez “ellas escriben cartas de amor”).

Ronan says he varied his translators – well established writers and poets such as Harry Cliften and Doireann Ni Ghriofa along with friends of his – because he wanted a mix of approach.

They did not have to know Spanish, but they did have to have a flair for putting words together.

“Often in poetry something mysterious happens which clicks a piece into place and people who have a way with words can arrange them to produce that vitality – I was not looking to create a purely literary exercise as often that is not how you reach people,” he said.

I’m sure would agree with that.

It was a real pleasure to chat to Ronan, he is such a personable and open fella.

Cuban Love Songs is an attractive and thought provoking addition to any lockdown home and the launch party, whenever it happens, sounds like it’s going to be a blast.

You posted me some handwritten background notes for this interview – which I loved – but why no computer?

I used to have one but when I lived with my girlfriend she found I was quite obsessive and could not get off it.

My son gave me a smartphone but I prefer to go to internet cafes to check my email and I write in the library with pen and ink.

I feel creative juices come more easily. It feels more personal, you are making shapes, they are manufactured by you and so belong to you. Does that make any sense?

When I am writing a book I do type it up eventually at the 11th hour.

So no social media for you?

I found it addictive, I don’t mean social media, but when I sent someone an email I would go back and check every few minutes to see if I got a reply. It was like a toy.

Some people use social media like an ongoing statement about themselves and I have no objection but it’s not for me.

Writers love gratification and social media can be like some form of publication. I have been involved with some projects but I found it undermines the currency of what you are writing. It just seems like it would be a distraction for me and a waste of my energy.

Where and when do you like to write?

When I am in good form with no distractions. I love to write in libraries. I often go to the one in Dún Laoghaire.

Why two decades to get Cuban Love Songs out?

There were many reasons why this was delayed. I was diagnosed as a manic depressive which took me out of action for quite a while.

I think I inherited this on my mother’s side. John Philpot Curran’s daughter, Amelia Curran, who was a friend of Mary Shelly and clearly manic depressive.

In the 1830s a Dublin doctor interviewed Amelia and described how she locked herself up for weeks on end and at other times would be bubbly and bright – so that was another side to it. I have not had a depressive period in many years now.

Is the lockdown getting to you?

The lockdown is getting to me in some ways; I can’t go to my usual haunts, I would usually go to Er Buchetto Cafe in Ranelagh every day – we buried one of my friends from there last Saturday which was sad – and like most derelict Irish men I hang around in bars.

In other ways I don’t suffer as I can get on with my reading and my work. The foundation of writing is thinking, meditation if you will and I find periods of isolation enhance that.

I don’t have a mortgage or young children – I have two grown-up sons – so I don’t have crushing responsibilities.

What are your favorite poems in the collection?

I am pleased they are all very readable.

I really like the piece by Caoimhe Lavele, Learning to Die, which is translated into Irish also, and Trudy Hayes’s translation of Blessed are the mean-spirited.

In my generation when something left wing was published it was typically on tatty paper and grottily designed. It was like an act of penance to open it and I was determined not to have a situation like that.

What was your childhood like and were you encouraged to write?

I was born in Dublin in 1953 and my four brothers and I attended Gonzaga College, just around the corner from my house. My sister Cathy went to Our Lady’s Templeogue.

In 4th year, my English teacher, Joe Veale, suggested I send a short story into The New Irish Writing Page in the Irish Press. I did and it was published. I was sixteen. In sixth class John Wilson taught us Spanish, focusing on the poetry of Lorca (Federico García Lorca), which I loved.

I still have not given Cathy back her Penguin edition which I nicked.

I studied English and Latin in UCD and continued to write stories for ‘The Irish Press’ some of which were published, one winning a Hennessy Literary Award in 1974.

Another winner that year was Dermot Healy and we became friends. One of the judges was Edna O’Brien.

When I finished my BA, I studied law and became apprenticed to my father, a solicitor in Dublin. I eventually qualified in 1980 along with my brother Maurice.

Jerry would follow a few years later. Garrett had preceded us and had set up his own firm. So I combined doing law with writing and editing – for Co-op Books and ‘The Crane Bag’ magazine.

Much later in 1999, Theo Dorgan asked me to become a director of Poetry Ireland which, under his direction, became quite a large arts organisation. The Peace Agreement in 1998 had boosted morale in the country generally so it was good timing.

My family have always encouraged my writing, especially when things were bad. Many sponsored Cuban Love Songs.

In the mid-nineties when I was diagnosed as manic-depressive, this effectively ended my career as a practicing solicitor. From time to time I act as a consultant in copyright law.

The main thing I did was a project on the first-ever recorded copyright case, involving the Irish Saint Colmcille in the Fifth Century.

You say José Julián Martí Pérez, the Cuban poet, essayist and revolutionary philosopher, was an influence on you – can you tell us a bit about him?

I first came across the work of José Martí when I heard the Carpenters sing Guantanamera, his composition, in the 1970s.

Like thousands of others I instantly fell in love with it. Marti was a Cuban patriot and is the father of the Cuban Revolutionary Party (1853-1895).

His literary and political career is suggestive of the Young Irelanders ( a political and cultural movement in the 1840s committed to an all-Ireland struggle for independence and democratic reform).

He opposed slavery. He lived in New York in the 1880s and ’90s where he met the Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío and possibly Oscar Wilde.

He believed Latin America countries needed to know their own history and to produce their own literature, a view that echoes in the writings of Patrick Pearse.

A book of Martí’s poems, Versos Sencillos (Simple Verses), was published posthumously. He died in battle in 1895, fighting for Cuban independence from Spain.

Are you writing at the moment?

I’m about to resume working on a political novel called Green Street.

It is sad the pandemic has stopped launches – when do you plan to hold yours?

I would love to launch Cuban Love Songs with a fun party – music, dancing, Caribbean food. And yes, lots of rum. We will just have to wait until it is possible.

Can you list some of your favourite writers?

Claudio Magris, Alejo Carpentier and Jorge Luis Borges.

Why should people buy this book?

Cuban Love Songs represents a unique encounter with Cuban poetry by Irish people. If you find the idea of Cuba exotic and exciting, you should buy it.