Ruth Ennis talks to author and illustrator Ashwin Chacko about playfulness, imagination—and not being afraid to fail.

by Ruth Ennis

You describe your work as positively playful—why is that important?

It took a while to hone into that place of “positively playful.” It comes down to my “why,” which is to bring joy and encouragement to everything I do. That’s the core element. I believe style is the bridge between who you are and what you want to say, and “positively playful” fits that messaging nicely.

I also think it came out of Covid and the 2020 lockdown, I wanted to be a positive voice on the internet. There was so much hate and fear and disillusionment. Instead of being sucked into it, I asked “how could I be a positive light in this?”

When it comes to “playfulness,” I believe all creatives should have a practice of play, because play is intuitive.

It’s something we grew up with as kids. Play helps us do three things: it helps us clarify our ideas, it helps us to innovate, and it creates opportunity. When you play, you explore your curiosity without the fear of failure. When you mix your curiosities together, you innovate. And when you innovate, that creates opportunity.

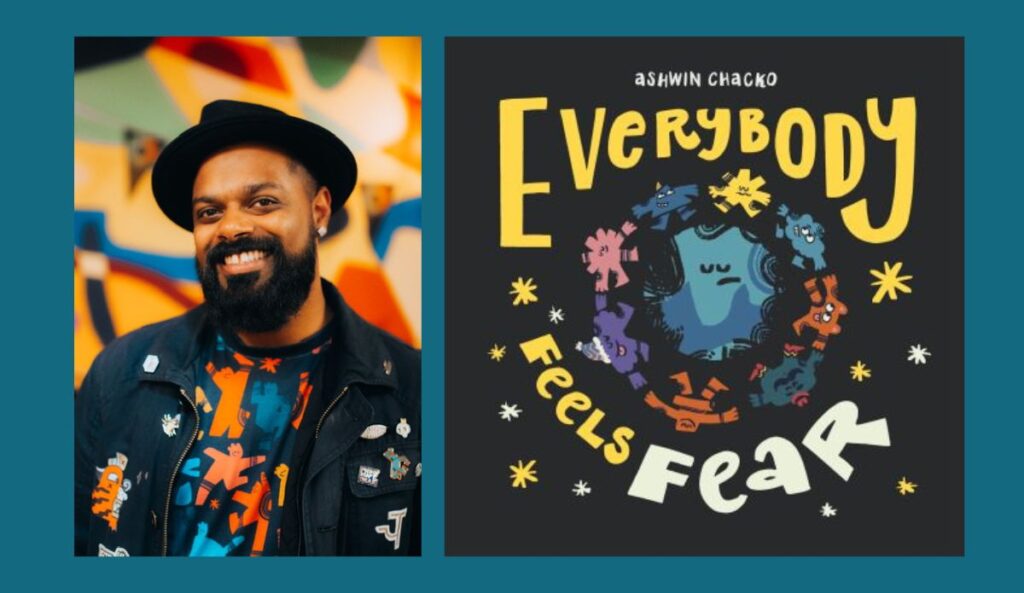

Ashwin Chacko is an Indian author, illustrator and motivational speaker based in Dublin.

He specialises in positively playful, visual storytelling to bring joy and encouragement. Author of Keep At It, Little Optimist, Everybody Feels Fear, A little book about Justice and What Wondrous Shapes We Are, his mission is to champion creativity and empower pole to find their inner spark.

Digital art tends to be your medium of choice—why?

Control+Z is what appeals to me! I can fix it in a second. I started traditionally; painting, drawing, originally doing it all by hand. Then I got access to computers, Photoshop, I got my first Wacom. I used to do it by hand, scan it over to my computer, and redraw it digitally. It took forever.

Digital is great, especially when you’re working in advertising. Your timelines are super tight, with a day’s turnover sometimes.

It’s really handy because you can get a lot of the same textures and tones as traditional mediums, but you can do it faster. You can make changes faster as well. The end product is flexible; where it can live in so many different mediums beyond that first image. Whereas with traditional art, there are some limitations to that.

Has your other graphic work ever influenced your approach in creating children’s books? Are the creative processes very different?

I don’t think it’s that different when it comes to producing the artwork. That comes from the same thought process. But with storytelling, writing books, it’s a longer process. With children’s books, there’s more time spent in ideating, clarifying that idea, and writing it – that’s the hardest part. But when the idea is clear, it’s just a matter of doing it, and that’s the easy part for me.

When you do it for long enough, you get to a place where you can create systems for yourself.

Simple shapes is the answer to any character design, whether it’s commercial or in children’s books. I use the same system for both; just that in one system everything is consolidated into one image, whilst with the other you get to play a little more, stretch it out across multiple panels.

You have experience in both self-published books and, more recently, traditionally published books. Is there anything you learned through your self-publishing work that has informed experience with traditional publishing?

Yeah, one hundred percent. I understood the publishing world much better. As an author or illustrator trying to break into the industry and trying to get your story over the line, you’re thinking like an artist. You’re not thinking like a business.

When you’re self-publishing, you start thinking a little bit more about what goes into building a book. It’s not just the story or the illustrations; now you’ve got to produce it, pay for the production, you have to market the book, distribute it, etc.

Walking through this process myself has given me a better understanding of why traditional publishing houses are so specific with the books they choose to go with.

Rather than feeling bad about not getting a book through, you’d have a deeper understanding as to why that is. And you can start looking at the market and say: “Okay, what stories can I tell that are relevant to this publisher’s specific audience?”

Because each publisher will have a specific audience and their own way of doing things. Maybe you’re not right for all publishers, but you are right for certain publishers. It’ll help you find that niche.

How do you decide the topics you address in your picture books, specifically What Wondrous Shapes We Are and Everybody Feels Fear?

I think, for me, the stories that have the most impact are the ones that I have a personal experience with. What Wondrous Shapes We Are came from overhearing a conversation my daughter had with the neighbour’s kid.

My daughter tans in the summer, and the neighbour’s kid was like “Oh, you’re Black!” and she said “No, I’m not Black. My daddy is chocolate, my mammy is vanilla, and I am caramel.”

That was really funny, it was a fun moment. But then it got me thinking, how can we have this conversation about race, skin tone, and body shapes?

When my wife was growing up, she was anorexic and bulimic. She had a really bad experience with body image, especially with the media’s idea of what is good looking. So, there were these two histories, and What Wondrous Shapes We Are was a melding of the two. It was having that conversation of how we all come in different shapes, colours, sizes, but in the end, what matters most is that we’re all people.

Then with Everybody Feels Fear, it was a similar thing. It came out of Covid, there was so much fear all around us. I noticed how we, the adults, were all so busy panicking ourselves that we didn’t take the time to address this fear with the kids. I was thinking “how do we have this conversation about fear, dealing with fear, how even mammy and daddy feel fear, and that’s okay.”

It’s not a question about whether or not we feel fear, it’s a question of how do we deal with it? The whole book’s premise comes from that; bringing humour to an ugly situation, so they can laugh about it, but also coming way away equipped with the tools they need to face fear themselves.

What are you looking forward to working on next?

My new book is coming out in April 2023 with The O’Brien Press. It’s called Wild City and it’s all about using your imagination.

It follows the story of Lily and Tim as they go into Dublin city to meet up with their friends to go skateboarding. The premise of the book is that they turn boring, mundane things into exciting, adventurous things. For example, instead of riding the Luas, they’re riding a submarine in an underwater city.

At the time that I wrote it, everyone was still wearing masks, so when they’re walking down the street in Dublin there are masked aliens everywhere. It’s taking a look at the city from a child’s perspective.

I find that now so many kids are sitting in front of the TV or playing video games instead of using their imagination to explore exciting ideas and building worlds. Imagination is a powerful thing. It’s what brought us from “wouldn’t it be a great idea if we could communicate with someone across the world” to the telegraph to those chunky big phones to this computer that can fit in your pocket.

That is something that somebody imagined and it became real. I think we should be equipping our kids with ability to foster and build that muscle of imagination because it can have such huge effects in the future.

What is one piece of advice you would like to give an aspiring illustrator of children’s books?

Don’t be afraid to fail. The first book I did was rejected and I gave up on it for a while. Once you know what you want to do and why you want to do it, there will be ways for it to come to life.

It might not be in the way you expect, but if you’re passionate about it and make a plan, it can happen. We live in a very exciting time where we have access to our readers directly.

You don’t necessarily need a publisher if you don’t want one. Don’t let any gatekeepers stop you from producing the work you want to make.

Ruth Ennis is a children’s literature writer based in Kildare. Her writing has been included in several publications and she was awarded an Arts Council Literature Bursary in 2021 and an Agility Award in 2022.