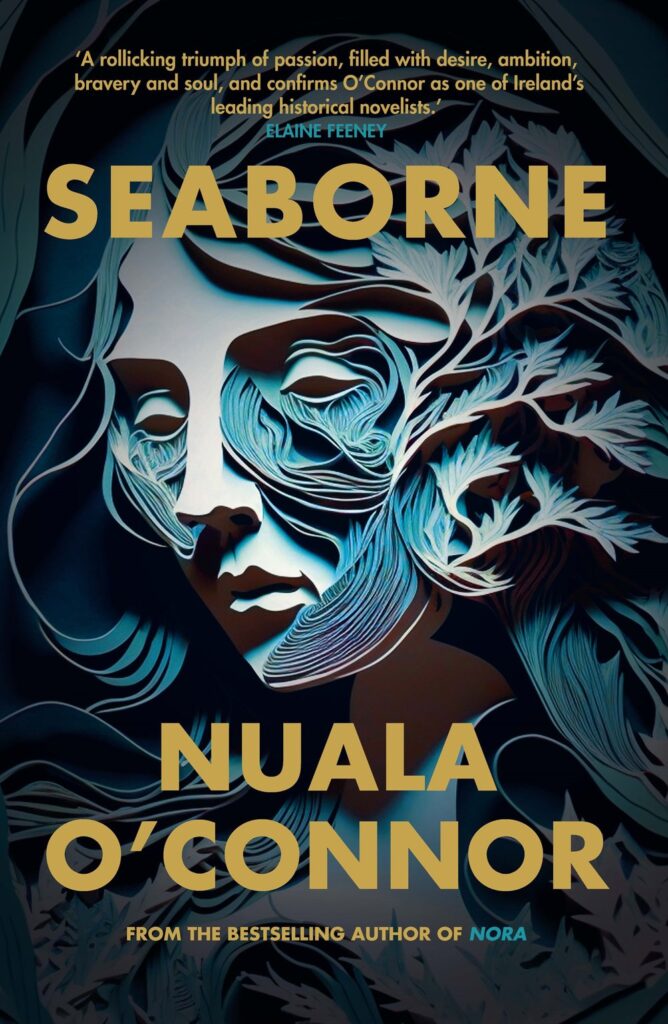

Seaborne|Nuala O’Connor|New Island

Seaborne—a visual, sensual novel with O’Connor’s hallmark lust for language

by Patricia O’Reilly

Seaborne, an artful novel of sublime imagination, tells the story of eighteenth century Anne Bonny, the pirate from Kinsale, Co. Cork.

Anne is the illegitimate child of lawyer Willard Coleman and his maid. O’Connor skilfully captures Anne’s carefree childhood as she grows up sailing in her tiny naomhóg, dressed as a boy called Anthony so she can masquerade as her father’s apprentice.

When the wagging tongues of the town force them to leave Ireland, the family sail to America and set up home in Carolina where Willard is employed in Hasty Point Plantation. Anne grieves for the sea that ‘ran in her veins’ and she aches for her days of wearing breeches. Dressed as a girl, she pushes against the role her parents expect her to play, although she develops a consoling ‘tenderness’ with Bee, an indentured servant.

When events turn Anne’s world upside down, she prowls the harbour where she meets sailor Gabriel Bonny, whom she marries. With Bee in tow, they escape Hasty Point and end up in Nassau. Anne rails against their impoverished life in a lodging house run by Mistress Spratt, a feisty female who befriends Bee. When the hoped-for dowry from her father isn’t realised, ‘melancholy drips’ from Gabriel. Anne envies his ‘skim into the blue,’ and is certain life would be simpler if she were Anthony, wearing breeches.

Calico Jack Rackman, with a penchant for red waistcoats, is handsome, well-thought of, and the first pirate to hoist a black pennant. Anne is smitten, and although Bee still occupies her ‘heartrooms,’ she and Jack plan a future together. She says she ‘knows not how to simply be,’—but she is sure Rackman is a sailor who will let her sail. Their desire for each other is a ‘ribbony thing that bounds them tight-tight.’ Masquerading as ‘sailor Bonn, a lean young tar of who-knows-where,’ she sets sail with Rackman, revelling in the dangers of pirating as though born to it.

O’Connor’s locations are both visual and sensual: the cold thrashy air of Bullens Bay; Hasty Point’s rice fields; Providence Island with the air lush and thick, like that in a laundry house on a wash day; then there’s ‘lovely Cuba…tobacco and pineapple galore…land as green-hued as Ireland with cloud-reaching palms.’

Written in first-person, Anne in all her fierceness and ambiguity comes alive; O’Connor gives us sex, and action of breath-taking courage and daring. She also depicts the domesticity of the times, which was never going to be for Anne — described by her father, as ‘three times trouble – red hair, forward manner and obsession with water and boats.’

Just as in her earlier work, Becoming Belle and Nora, O’Connor makes language her own with phrases like ‘a-ruckle with impatience,’ ‘money-sticky glares’ and ‘the night air still as rock-clutched barnacles.’ Her sentences are liberally spliced with similes: ‘sizzle like water on a griddle’; ‘innocent as crane flies ignoring jam’; ‘mouth dry as feathers’; and, of course, the onomatopoeia of the sea: ‘shush-whiss’.

In her note at the end, O’Connor points out that many of the tales about Anne Bonny and Mary Read have become more fanciful with the passing of time. Here though, it’s evident that she approached the making of this exceptional novel with ‘leery eyes’ and ‘a wide open heart.’