What life was like in Dublin, 1450 – 1540….

The walled city of late medieval Dublin, unlike today’s ‘commuter belt’ Dublin, was unbelievably small – one quarter of a square kilometre, centred around Dublin Castle and Christ Church. It had suburbs outside its walls: a semi-rural suburb along present day Dame Street and College Green; an ecclesiastical suburb dominated by St Patrick’s Cathedral; a linear suburb westwards along James’s Street and Thomas Street, and a suburb in Oxmantown, north of the river, with grid-like streets as in New York today.

The Liffey and its quays allowed merchants to reach Chester and pick up continental products. There was always a buzz on Wood Quay and Merchant’s Quay, with a crane capable of loading and unloading ships. Experienced apprentices also brought their master’s goods to Chester and got them through customs. John Wilkynson did such work, travelling 5,000 miles in a year, and Christina Clerke clocked up over 1,000 miles on a number of voyages. Young lads would have hung around the quays, rattling off navigation rhymes, and pestered ship masters to take them on a voyage to Chester.

The basic foods were available from Dublin’s fertile hinterland, from the Liffey and the Irish Sea. The Dublin municipal council ensured the flow of food into the city markets and attempted to maintain the hygiene of the city. The council watched out for hoarders who stock piled grain in the hope that the price would rise and they could make a killing. The problem of the disposal of human and animal waste was never really mastered, and a foul diseased stench hung over the city. Women were the brewers in the city and county – Agnes Laweles, on the family farm at Glasnevin, taught her daughter Rose how to brew, and Jacoba Payn, who lived in the shadow of St Patrick’s Cathedral, multi-tasked – she was a brewer, ran a clean inn with six rooms, and fattened twenty pigs in the back yard.

The Dublin authorities dealt with a serious political problem – defending Dublin, with its decaying walls and unprotected suburbs, against the belligerent Wicklow Irish. And then there was the enemy within, the Irish ethnic group in the city whose numbers seemed to be regularly topped-up by Irish beggars, Irish hermits and Ulstermen.

The merchants who set standards and passed by-laws for the smooth running of the city, were well capable of breaking the law. In 1487, they committed high-treason, supporting the crowning of a small boy, Lambert Simnel, as king of England, and lost. A decade earlier, Dublin merchants, pillars of society, were indicted for counterfeiting coins in Chester. It is hard to believe that one of those indicted, Matthew Fouler, was a bailiff of Dublin (second from the top in authority). And Patrick FitzLeones, a year after he was indicted, surprise, surprise, was elected mayor of Dublin!

Parents wanted the best for their child, the tried and tested way being to secure an apprenticeship with a master of one of the many crafts practised in the city, with qualification leading to the granting of citizenship. Women were apprenticed in Dublin and qualified in crafts such as butcher, cook, glover and merchant, but secured only ten per cent of the apprenticeships.

In the churches, something other-worldly happened in an atmosphere created by a combination of the use of candles, stained glass, plainchant, coloured vestments and the whiff of incense. However, a bombshell struck believers in Dublin in the 1530s – the Reformation arrived, and Dublin’s shrines were pillaged of £500,000 sterling (today’s money). Its beloved monasteries were desecrated – artillery was stored in the church at St Mary’s abbey – and Church buildings were stripped of timber, tiles and glass. Liturgical books were censored – the word ‘Pope’ blotted out because Henry VIII was now head of the Church in Ireland.

Dubliners were not always working. There were open air dramas, street pageants, drinking, playing cards, throwing dice, bull-baiting, and archery practice in Hoggen Green.

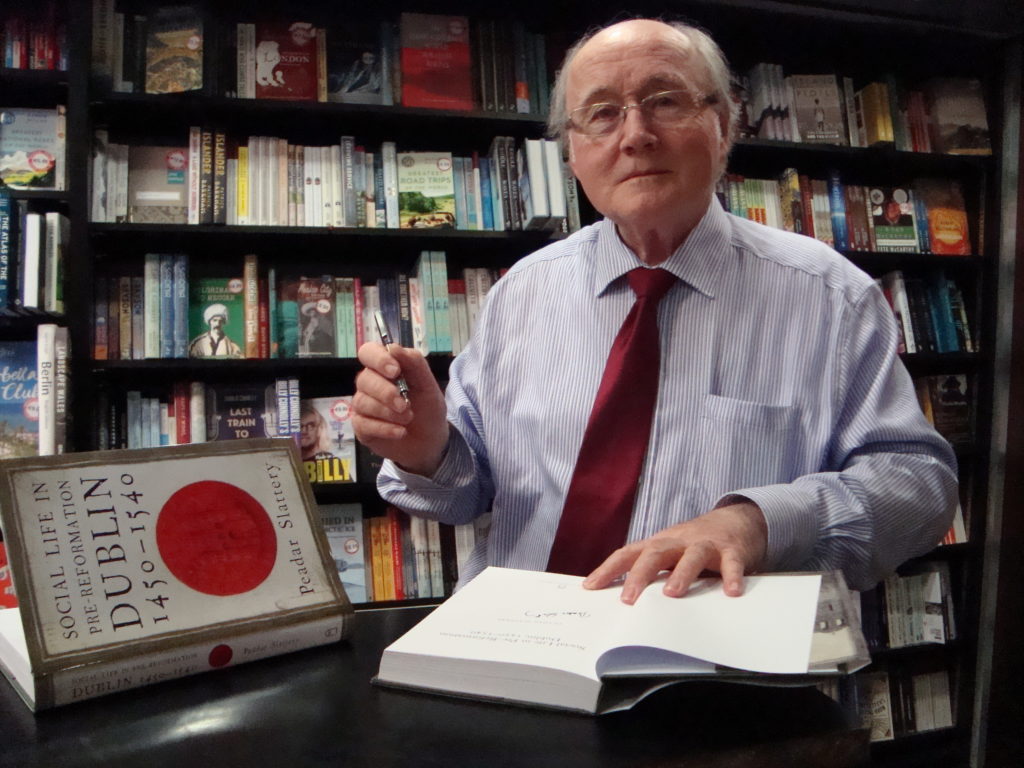

Social Life in Pre-Reformation Dublin, 1450–1540 by Peader Slattery is published by Four Courts Press. Available online and in bookshops.

Peadar Slattery was awarded a doctorate in modern history by Trinity College Dublin and has published a number of articles on timber and wood in medieval times in Ireland.