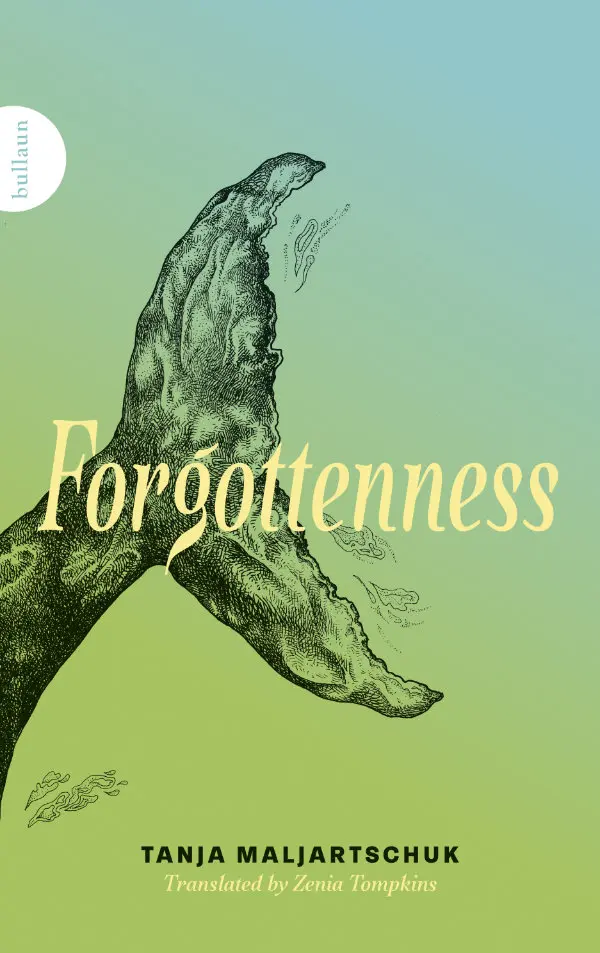

Forgottenness|Tanja Maljartschuk|Bullaun Press

“How can one live with the overwhelming debts of history, and how are they paid off? To what extent are the living beholden to the dead?”— Forgottenness by Tanja Maljartschuk

by Eoghan Smith

Tanja Maljartschuk is a multi-award-winning writer from Ukraine, now resident in Vienna. Her latest novel, Forgottenness, won the BBC Book of the Year (Ukraine) in 2016, and has attracted a good deal of critical attention since its publication in English in a fine translation by Zenia Tompkins. This attention is rightly justified: Forgottenness is a complex and absorbing story of the intersections, and indeed gaps, between the minutiae of personal identity and the trauma of Ukrainian national history, exploring how identity is rooted in language, history and land.

The novel weaves two different narratives. One is set in the present day 2010s, related in the first person by an unnamed female writer who suffers chronic loneliness, anxiety, agoraphobia, and obsessiveness over her health. The other is altogether different. Sketching the political and personal life of the largely forgotten Ukrainian political thinker and diplomat, Viacheslav Lypynskyi, this second narrative in the third person has the quality of biography. Alternating between chapters headed ‘Us’, ‘Me’ and ‘Him’, the two narrative styles – one intimate and introspective, the other retrospective and more dispassionate – make for very different reading experiences. However, they do not jar, and taken together they emphasise the gap between the subjective and the objective, the immediate and the historical.

the two narrative styles – one intimate and introspective, the other retrospective and more dispassionate – make for very different reading experiences

Through this method, the reader’s attention is drawn not only to the disjunction between the past and present but also to the impossibility of bridging the gap between them. Yet though they are separated by time and experience, there are a number of commonalities between Lypynskyi and the female narrator: both are literary figures in their own right, both experience difficulties in their relationships – Lypynskyi’s marriage is unhappy, while the female narrator has three successive, aborted relationships with ‘golden-haired men’ – and both are wracked by illnesses (the female writer believes there is something wrong with her heart; Lypynskyi suffers from tuberculosis – the book also has a focus on the body).

The story Maljartschuk tells is of Polish and Russian hostility towards the idea of a distinct Ukrainian identity in the first part of the twentieth century

The two narratives are linked by the female writer’s interest in Lypynskyi, whom she first discovers from an old newspaper clipping from the 1930s reporting his death. Unaware of who he was, she begins to research his life, and in doing so she recovers through Lypynskyi the tumultuous early history of the Ukrainian state. The story Maljartschuk tells is of Polish and Russian hostility towards the idea of a distinct Ukrainian identity in the first part of the twentieth century, the bitter competition between forms of Ukrainian nationalism, the pursuit of Ukrainian statehood from the ashes of the first world war, and, in particular, the disintegration of Lypynskyi’s own political ideals and ambitions for Ukraine in the face of aggressive sovietisation after the Russian Revolution.

Lypynskyi, we learn, comes from a landed family who regard themselves as Polish; Lypynskyi begins to fashion himself as a Ukrainian – insisting that he be addressed by the Ukrainian and not Polish variant of his name – much to the derision of his family, as for them the Ukrainian language is little more than a peasant dialect. His soon-to-be wife, Kazimiera, a native of Krakow, never quite overcomes her repugnance towards Lypynskyi’s Ukrainain identity.

the price of his efforts come at the expense of his marriage, his relationship with his daughter, and, ultimately, his health

Lypynskyi, whose nationalism is fermented at university, is depicted as a determined, rigorous intellectual. He first develops and then publishes a history of Ukraine that depicts a people who have been historically suppressed but who will soon take their place as a nation among the others. Later he becomes embroiled in Ukrainian politics and eventually becomes an envoy of Ukraine, and while never a central figure in shaping the destiny of the country, he remains relentless even when his political career ends in relative obscurity: the price of his efforts come at the expense of his marriage, his relationship with his daughter, and, ultimately, his health.

The history in Forgottenness is tumultuous and its canvas is broad, covering roughly a period from 1900-1931: political movements rise, global conflict breaks out, empires fall, the entire map of Europe is re-shaped. Internally in Ukraine, a succession of governments and ideologies compete for power in the new post-World War 1 State. Geographically, the story takes place across many major cities in Eastern and Central Europe: Krakow, Kyiv, Vienna. And yet Maljartschuk does not dwell on the large-scale: her account of the emergence of Ukraine is filtered almost entirely through Lypynskyi’s efforts to promote a form of agri-statism (Lypynskyi initially studies agriculture at university before becoming interested in Ukrainian history and language).

Maljartschuk does not dwell on the large-scale: her account of the emergence of Ukraine is filtered almost entirely through Lypynskyi’s efforts to promote a form of agri-statism

Lypynskyi’s principle idea is to unite Ukrainians by common ownership of the land of Ukraine; it is distinct from the blood bonds of the ethno-nationalists, or the class warfarists of the Bolsheviks. Lypynskyi’s vision for Ukraine belies his own gentrified background as he argues for the restoration of a type of Ukrainian monarchy, an idea which is anathema to the eventual soviet rulers, and which brings trouble to him and his family. Like other political and cultural figures in Ukrainian history, Lypysnki is forced into exile.

Lypynskyi’s displacement is echoed at an existential level in the story of the female narrator (‘why did he, Lypynskyi, even exist?’ she asks in a Camusian moment). She worries, first and foremost, about Time. Time devours everything, she observes, it consumes people and their histories until, like Lypynskyi, they are forgotten. And yet, history is felt everywhere: its traumas erupts in her anxieties and habits: she struggles to leave the house, she develops unusual eating habits, she develops hypochondria, she finds it difficult to maintain relationships. Yet if her story and Lypynskyi’s are entirely different, it is because the gap between her and Lypynskyi can never be bridged: ‘our lives’, she says at the beginning of the novel, ‘are too disparate to fit comfortably into a shared narrative’. There is, we are given to understand, a limit to the work that the imagination can do. But this does not mean that Lypynskyi’s story and hers are not connected in tangible ways.

Time devours everything, she observes, it consumes people and their histories until, like Lypynskyi, they are forgotten

Through her own family experience, we see the effects of the tragedy of Ukrainian history as it played out after Lypysnki’s death. Her grandmother Sonia survived famine in the early 1930s, while her grandfather Bomchyk refused to fight against the soviets and handed over his property to them. In such moments, Maljartschuk alerts the reader to how individual people’s decisions in response to political realities have a profound generational effect. The narrator reflects:

Between a slavish existence and a heroic death, he chose the former, and only thanks to this choice did I become possible […] I’m the offspring of meekness in the face of power and fear in the face of death. And the price that had been paid fell on my shoulders. Through the generations, considerable interest had accrued.

How can one live with the overwhelming debts of history, and how are they paid off? To what extent are the living beholden to the dead? These overwhelming questions contribute to the psychological and existential breakdown of the narrator. In a moment of panic outside her apartment, she suddenly experiences ‘shame and powerlessness’. ‘The battle was lost’, she says, ‘the decision was made to never engage in it. That’s why I couldn’t even call this defeat; it was something more than that. It was dishonour’.

How can one live with the overwhelming debts of history, and how are they paid off? To what extent are the living beholden to the dead?

Lypynskyi and the female narrator are both writers: Lypynskyi was a prolific writer in multiple forms: history, letters, political tracts, while the woman is a writer of fiction. Forgottenness in this sense is about books and the power of writing to convey ideas. But there is a sense in the novel that while writing stages contests between history and fiction, the real and the ideal, the past and the present, ultimately it all comes to naught. Lypynskyi’s own efforts to persuade Ukrainians of the value of a monarchical society built on fidelity to the common land end in acrimonious disenchantment. More recently, Maljartschuk has expressed her own profound dissatisfaction with fiction. Reading the novel in the present moment, one cannot escape the context of the Russin invasion of Ukraine in 2022, but it is worth remembering that Forgottenness was originally published in 2016. Maljartschuk herself has not published any new fiction for some time and she has said recently that she ‘doesn’t see any point in fiction anymore’. She has also conveyed a sense of profound pessimism about the state of the world:

I don’t have a very high opinion of humanity’s efforts. It is still irrational enough to self-destruct. So much has already been destroyed and killed, and there is no end to this barbarism […] As a writer, I cherished the illusion that I could change at least something in this world for the better with my words, contributing, in a way, to goodness. And it turned out that literature does not prevent the most senseless wars from happening again; dictators and tyrants are still there, and they even read books.

there is a sense in the novel that while writing stages contests between history and fiction, the real and the ideal, the past and the present, ultimately it all comes to naught

There is an echo in these comments of Lypynskyi’s own profound sense of disappointment. Then, what is literature for in the world today? Forgottenness will remind readers that well-meaning sentiment about the necessity of literature will not suffice alone in a world of unbearable savagery. And yet here is also utterly compelling piece of literature that also reminds that History – with a capital H – is made by individuals who fail, each in their own way:

The blue whale will suck it all away: everything that Lypynskyi fought for and lost, his pain, his hatred, everything that he saw and felt, his body, his illnesses, his memories, his Ukraine.

If a profound sadness pervades this novel it is because all things – all those physical and intellectual efforts, all those passions – are swallowed up by time.

Eoghan Smith is the author of The Failing Heart (2018), A Provincial Death (2022), and his latest novella, A Mind of Winter is out now with Dedalus Books.