“The Gone Book is teenage me, trying yet again to traverse the ‘in between’ but this time I am a fifteen-year-old lad in present-day Limerick.”

As a writer, I try not to think in genre. I think in story. It takes months and a lot of composting to decide on a voice. Often, that voice for me is a teenage one. I found my own teenage years to be difficult, confusing, sad. Not quite an adult, certainly not a child anymore, there was an ‘in between’ space that was weird and brilliant and terrifying. I knew the rules of one world—childhood—and the adult world presented new rules, sometimes no rules, and a whole mess of other stuff thrown in.

The Gone Book is teenage me, trying yet again to traverse the ‘in between’ but this time I am a fifteen-year-old lad in present-day Limerick. All the same markers are there: adults with no rules, adults with rigid ones, adults still in that grey place they should have shed years ago. Perfect writer fodder.

The setting, Limerick, is ever present in my stories. A city I love/hate; a mad, raw, energetic town with no notions about itself, sliced down the middle by the majestic Shannon, which gives so much, but takes so much too. A city obsessed with sport—Thomond Park and the Gaelic Grounds are our temples, the gathering places of our tribe. It’s a city that has suffered neglect through the years, parts of it ignored and abandoned. There are myriad stories in that neglect. Stories that should be told and heard.

The Gone Book celebrates these places, gives faces to the abandoned, allows us a snapshot of contemporary teenage life in a complex city. Matt, the protagonist, seeks comfort in his environment. He skateboards through this landscape, showing us Limerick through his filter. We get to live his summer with him, a milestone summer, when his mother, who abandoned him and his brothers years ago, shows up with a brand-new family. The Gone Book is also about friendship, connections that go beyond blood and hold huge importance in life, even though a teenager may not realise it at the time.

But, ultimately, the novel is about the ‘in between’ time in a teenager’s life and portraying that in a realistic and relatable way. We have the voice, the setting. Now we need the language and the experiences. The subtle inflections in dialogue, the use of the vernacular and the—sometimes—controversial use of what is termed ‘bad language’. I wrote the story with no genre in mind. That’s how I write. It found a home as a YA novel but to me it’s suitable for a fifteen-year-old and an eighty-year-old. Most stories are. I have to be true to my characters. They swear. Most teenagers do. It’s not Five Go Down to the Sea for teens. It’s an attempt at capturing the world through teenage eyes in a realistic, contemporary way. My characters cross paths with alcohol, drugs, danger. Most teenagers do. They behave angrily, stupidly, kindly, selfishly. Most teenagers do. Bad things happen in the world, no matter what age you are, no matter where you are from.

When the novel came out, a brilliant Limerick singer-songwriter, Emma Langford, read it and loved it. She asked me if she could do a reading online. At this stage, the scourge of present times had shown its ugly face and the arts world was (and still is) bereft. No book launches, theatre, readings and, in Emma’s case, no live gigs. I said yes to Emma because I love her music. ‘The Seduction of Eve’ is one of my favourite songs in the world. I was nervous and didn’t listen to her reading for two days. Would she get the vernacular pitch perfect? The nuances of language, the characters’ personalities and different voices? I needn’t have worried. She did it beautifully and—dare I say it—better than I could have myself. You can hear the youth in her voice and of course she is pitch perfect. I should never have doubted her and if there is ever an audio book of the novel, then she’s my first choice. Below is a link to her reading.

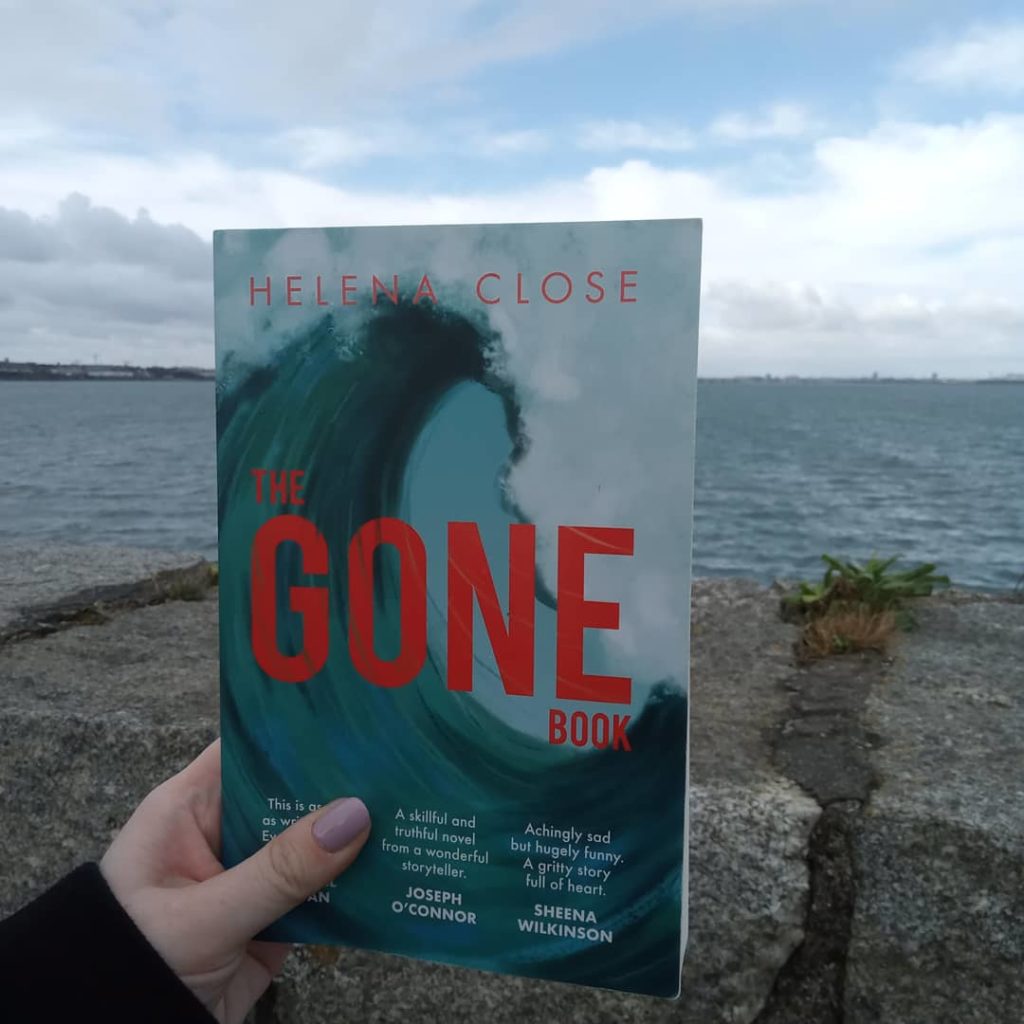

The Gone Book (pb €9.99) is out now from Little Island and bookshops.