“Virginia Woolf wrote that ‘Literature is strewn with the wreckage of those who have minded beyond reason the opinion of others.’ “

— Amanda Bell talks with poet Eleanor Hooker

The darkness echoing

by Amanda Bell

Eleanor Hooker inhabits many worlds.

in her literary life she is a founder member of the Dromineer Literary Festival (2004-17), curator of Rowan Tree Readings, and a widely published, translated, anthologised and respected poet, known for her generosity and kindness towards her fellow writers.

In her other lives, she is Fellow of the Linnaean Society, helm and press officer for the Lough Derg RNLI Lifeboat, and has been both intensive care nurse and midwife.

More than most, she has had the ‘terrible privilege’ (from ‘The Thing We Carry Now’) of being present when the veil between the spiritual and material worlds is at its thinnest, of accompanying the dead on their way through—an experience that infuses her work with a shape-shifting, otherworldly character.

Demons lurking

The Shadow Owner’s Companion, Hooker’s first collection (Dedalus, 2012), evokes Seamus Heaney’s ‘Personal Helicon’, both in its fascination with chilly, watery places, and its expressed need to write in order ‘to see myself, to set the darkness echoing’.

Throughout this haunting and haunted debut we find an attempt to ‘map out the landscape between the interior childhood world of terror and wonder and the exterior adult world of surreal reflections.’

The voice of the adult is in constant communion with multiple previous selves, fearful and wary, who compete for attention.

The poet looks to her contemporaries for direction, but her own voice demands to be heard: ‘I have only demons lurking in the murky depths, razor-toothed / preying fish.’ To those who question why these dark stirrings demand expression she can only reply ‘It is to / not be mannered, to not belong / to anyone, not even myself, / that I write.’

Amanda Bell speaks with Eleanor Hooker

Amanda Bell

Eleanor Hooker

Voice

How hard was it for you to find—or to accept—your voice as a poet?

I used to worry that inviting readers to follow my imagination into the dark might put them off, or that they might think me odd.

To succumb to such notions is paralysing and inhibits your writing, so you have to let them go. Virginia Woolf wrote that ‘Literature is strewn with the wreckage of those who have minded beyond reason the opinion of others.’

Finding your voice means learning your craft and honing your writing skills, and I believe that’s an ongoing project for me, poem to poem. I like the idea that multiple voices can offer a multiplicity of perspectives.

A Tug of Blue

Having established your voice in the first collection, which was shortlisted for the Shine Strong Award for best first collection published in Ireland in 2012, the second, A Tug of Blue (Dedalus, 2016) delves further into shadowy waters, simultaneously exploring the figure of the father and the great inland sea that is Lough Derg: ‘from my father’s side, I am part fish.’ Corporeal bodies are damaged, bruised, drowned, subject to symptoms of betrayal, and to live is ‘a sort of quantum / mischief that answers to its / own logic’ (‘Living’).

Poems in this collection feel like dialogues – with both previous selves and ethereal presences, ghosts and angels, dream creatures and daemons communing outside of time.

With the death of your father seven years ago, loss becomes real and present, moving out of the dreamscape to step into the here and now of chronological time. Time seems to be a recurrent motif in your work, seen variously in clocks, ticking, dreamtime. Can you tell me how the sense of time influences your work?

Time

Once, during a conversation about time with our boys on one of our twelve-hour drives from where we were living in Newcastle-upon-Tyne to our home in Ireland, my son George said he thought ‘time’ was the fourth dimension.

When I asked him what he meant by that he answered, ‘well, with three dimensions, you walk around a tree, in the fourth dimension the tree winds itself around you’. It was utterly fascinating; I’ve never forgotten it. George was six. Six!

It’s comforting sometimes to think of time as interlocking loops and corridors, a dovetailing that allows presences travelling through those corridors to catch up and move past.

This idea features in some of my poems. To quote Eavan Boland ‘I stumbled on one of the essential timekeepers: A magic permission to make time a fiction and the imagined life a fact’ (from A Journey with Two Maps: Becoming a Woman Poet).

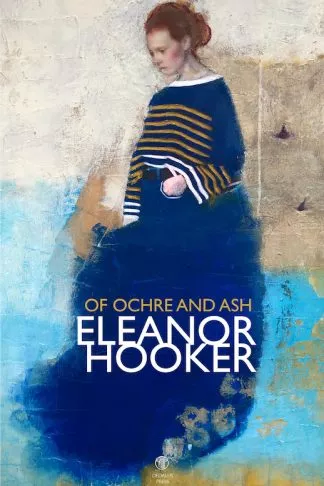

Of Ochre and Ash

You have said that ‘creativity is often dependent upon contradictory and competing forces, and like shadows, is formed when light is blocked by an object or body.’

The original title of this book was to be Mending the Light, and there is a multiplicity of references to light in the new collection, both visually and symbolically. The title Of Ochre and Ash suggests both colour and scent, and creates a different sensory impression. Was this a significant change as the book came together?

Healing and survival

When I’m writing poems my only concern is that poem at that moment. However, as I began to think of my next book and consider the poems as a collection, themes became apparent, especially around healing and survival.

‘Mending the Light’ as a title seemed appropriate. As I pruned, and cut poems I felt were not working, and added others from the ‘maybe’ pile, additional themes of earth and nurture emerged.

When I submitted my manuscript to Pat Boran, editor at Dedalus Press, we discussed whether the working title was still appropriate.

Essence of the poems

I recalled the line ‘of ochre and ash’ from my poem ‘When you Dream of the Dead’, and I liked the associations that ochre and ash brought to my mind. Ochre is a natural clay earth pigment, used in Palaeolithic cave art and by Australian Indigenous Cultures in their Dreamtime art.

For centuries ochre was used for its healing properties, possibly due to the astringent qualities of its ferric oxide content.

The ash is a treasured, traditional Irish woodland tree, and the word ash also refers to grief or to the residue after something is burned. These connotations matched the essence of the poems in the collection, so Of Ochre and Ash became the title.

Confidence

The voice in Of Ochre and Ash is perhaps that of the ‘authentic self’ of ‘All My Imperfections’, stepping out of the hall of mirrors, taking her place in a matrilineal line which includes mother, grandmother, and godmother.

It is fitting that the cover image portrays a woman half turned towards the viewer: the cover images of previous collections had a woman viewed from behind (A Tug of Blue), and a shadowy silhouette (The Shadow Owner’s Companion).

There seems to be more confidence in standing your ground as a poet, combined with a strengthened sense of self-preservation, as seen in the line ‘Entrust your melody to strangers, never your song.’

‘Startle empty corners with song’

The eight-poem sequence ‘Legion’ relates to the writing of poetry using the honeybee as an analogy. In Part VIII: ‘Interview With Honeybee as Poet’, you pose five questions. These are 1. What persuaded you? 2. Who are your people? 3. What is the speed of dark in your poems? 4. What is your view? and 5. What is your advice? Does the poem answer these questions to your satisfaction, or would you like to elaborate here as a poet rather than a honeybee?

I am fortunate to know poets who care deeply for one another, who check in, who are collegiate and who understand the fragility of existence and importance of friendship, support and kindness.

I have encountered others who seem to hold with Gore Vidal that ‘It is not enough to succeed. Others must fail.’

There is nothing wrong with ambition for one’s writing or career as a writer, but never at the expense of your humanity. The final verse in this poem is my mantra, my philosophy for life. The honeybee nailed it – Startle empty corners with song.

Earth, body

Of Ochre and Ash is less intensely water-focused than the previous collections, delving instead into the belly of the earth, and simultaneously into the corporeal self.

The earth/body analogy is explicit in ‘A Landscape Forfeited to Snow’, a disturbing Cronenbergian representation of the poet entering her own body through an incision, and exploring the treacherous landscape within, where ‘[a]side from your birds, and the many versions of yourself / drowned in the ice, you are sole citizen, those voices / are echoes of a lifetime speaking to ghosts.’

‘Eating the Earth’, a visceral portrayal of rural isolation and alienation which sends shivers through me each time I read it, ends with the poet ‘rooted to the vernacular of the earth, on whose life my life depends.’

There seems to be a strong ecofeminist stance here, with the overt parallel drawn between the woman’s body and the earth.

This analogy also forms part of an Irish language tradition, for example the work of Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill. Were you conscious of literary forbears in this approach, and would you consider yourself an ecofeminist writer?

Resisting labels

Writers do form a community, but are not one tribe. Labels or designations make me anxious, so I resist them. They constrain creativity. They set up an expectation that readers will reliably find elements in a poet’s work for which they think they are known.

And for me, surprise, range and experimentation are freedoms I cannot surrender in order to belong. I think it’s possible to express social and ecological awareness without it being associated with gender, so I would resist the label ecofeminist.

Mothering

You have said ‘I now know that poetry is capable of holding it all up to view – the breakable and the infrangible, the forcible and subversive, and by some alchemy, changing everything in the process.’

The subject of mother and baby homes has been explored in depth in recent poetry projects, from Kimberley Campanello’s visual and conceptual Mother Baby Home to Annemarie Ní Churreáin’s Bloodroot and The Poison Glen.

From a point of personal experience as a midwife, you delve into the darker realms of Ireland’s difficult history as regards mothering, presenting a more oblique but all the more devastating critique of women’s reproductive experiences.

These are poems where the earth itself whispers of the secrets interred in her: “We hear the swaddled drop, and hear the earth catch // her breath, as each stilled birth is infolded to her breast, for long may she cradle them, we beseech, before the descent, the pandemonium.’ Can you elaborate on this approach?

Deadening history

I found, over the years nursing in ICU, that compassion and humour were powerful tools with which to demystify events on the unit for relatives terrified for their loved ones.

This demystification gave families permission to talk, to speak above a whisper and most importantly to assist with care, bed baths and such.The sights and sounds of machines plugged into patients to support their life, can make Intensive Care Units extremely intimidating for visitors.

Describing that setting in poetry is easy, whereas describing the deadening history of objectification of pregnant women in Ireland is not.

For the latter I went dark, and though I had seen and experienced much that was good, I also saw much of what remained of the Church’s prurient claim on female autonomy, their bodies, and their souls.

At the very first poetry workshop I ever attended, Tipperary poet Michael Coady told our group that if writing is a rant, it is, in his opinion, failed writing; readers don’t want to be heckled or lectured. I keep that thought with me whenever I’m at my desk.

Without constraint

There is a strong underlying critique of the church in your work, and a leaning towards myth and folklore. Do you see these as conflicting traditions in Irish society?

I have difficulty with institutionalised religion, with fundamentalism of any stripe. I am a spiritual person, but my communion with Herself might be out rowing my boat or climbing the Galtee Mountains with my family or chatting with friends and family by the fire. Simple things.

Nevertheless, when I go into a church and listen to the human voice raised in song I am moved to my core.

Myth and folklore enable us to speak without constraint, outside the authority of politics, power, and the Church. Difficult life themes reimagined as myth or folklore, but populated by recognizable people and rules, provide an opportunity to subvert norms, to speculate, and to be honest.

Amanda Bell‘s debut collection, First the Feathers (Doire Press), was shortlisted for the Shine Strong Award for best first collection in Ireland.

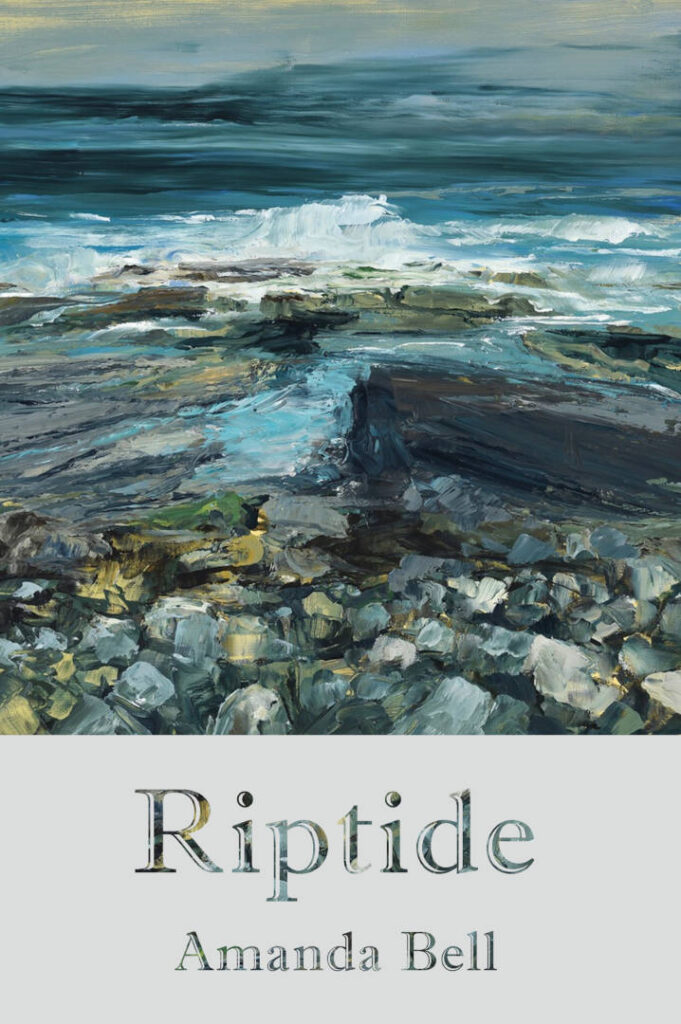

Other publications include Undercurrents (Alba Publishing, 2016), which was shortlisted for a Touchstone Distinguished Books Award. Her latest collection, Riptide, is out now with Doire Press.