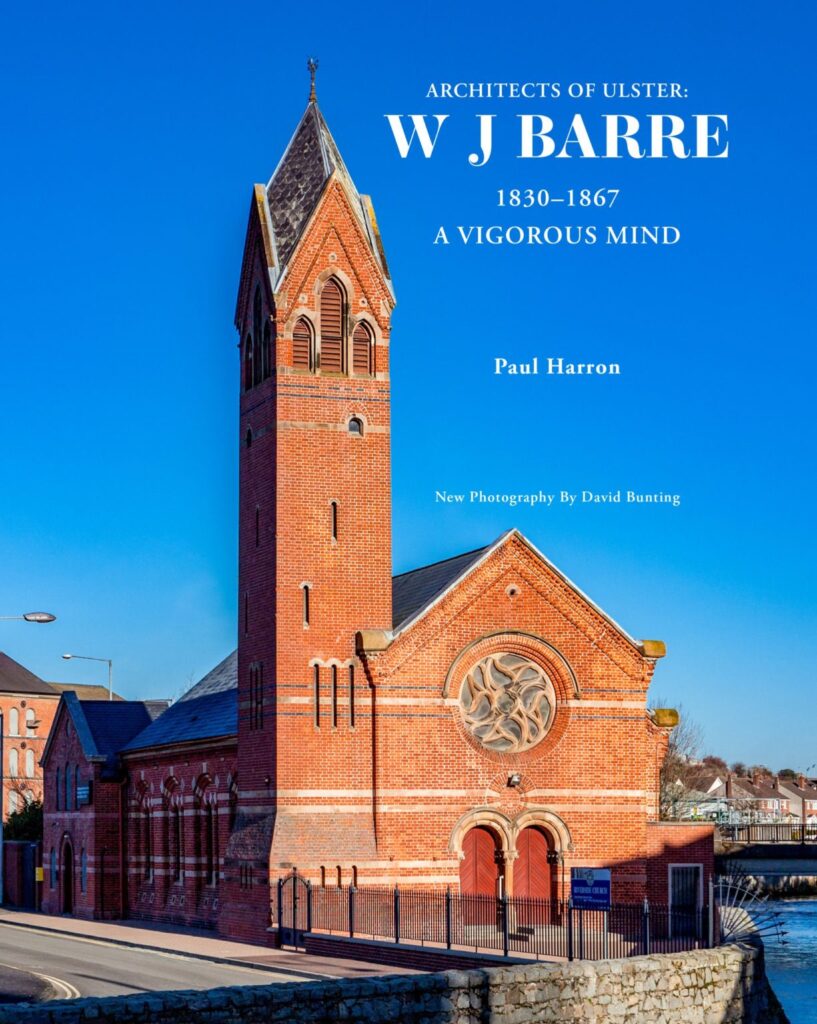

WJ Barre, 1830-1867: A Vigorous Mind|Dr. Paul Harron|Ulster Architectural Heritage|£28

“It might be argued that the buildings he left behind give us an insight into Barre’s character: bold, imaginative, intricate, wide ranging and complex.”

by Tony Canavan

I first came across the architect WJ Barre when I was curator of Newry Museum, as he had designed many buildings in the town.

When I came to write Frontier Town: an illustrated history of Newry, I mentioned him in the context of the town’s prosperity and growth in the nineteenth century. Paul Harron is kind enough to mention my book in this biography of Barre, part of the Ulster Architectural Heritage Society’s Architects of Ulster series. It is a handsome production which would grace any coffee table with its many photographs, sketches and architectural plans.

However, this is more than a coffee table book. It has six substantial chapters as well as a gazetteer of architectural terms, an appendix of Barre’s competition entries, notes and a bibliography.

Detailed study

Harron has written a detailed study of one of the most important architects in the North of Ireland at a time of rapid change and industrialisation. Barre was born in Newry where he began his training as an architect with Thomas J Duff. On Duff’s death, Barre went to Dublin to complete his training with Edward Gribbon.

This was a time when the professions as we know them were beginning to consolidate and Barre could just as easily have become a quantity surveyor or even an artist as he was skilled at drawing and painting.

However, he returned to Newry in 1850 to work as an architect and he was to spend the remainder of his short life working in Ulster.

Genius

Barre was undoubtedly an architect of genius. He pioneered the Gothic Revival style and persuaded some unlikely clients, such as Presbyterian churches, to adopt it. Harron draws attention to St. Annes’ Church of Ireland in Dungannon as his “Gothic Revival masterpiece”.

Besides this, he was able to work in different styles and across a range of buildings from the religious to the commercial as required. In Newry he was responsible for the Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Church, Thompson’s warehouse (now a parish hall) and the Glen, a palatial private residence, among other things.

Belfast

In 1859 he won the competition to design the new Ulster Hall in Belfast and so moved to that city. He was from then on a Belfast architect who won commissions not only in the city but in the neighbouring counties.

While in Newry, Barre had joined the Freemasons, a not uncommon practice among young men hoping to get on in business. However, he was to learn that masonic connections did not always guarantee success.

In 1856 Barre was selected to design the memorial to the Marquess of Londonderry at Scrabo, Co. Down. In controversial circumstances, the commission was withdrawn and awarded to Charles Lanyon instead. The latter was to be Barre’s great rival and is remembered today as the premier architect of Victorian Ulster, designer of Queen’s University Belfast among other things.

The Londonderry monument was not the only awarding scandal that Barre lost out on, as Harron chronicles in this book.

Depth and colour

Barre’s early death from a lung infection is not the only difficulty facing a potential biographer, as shortly before his death Barre ordered that all his papers be destroyed.

Hence it is difficult to paint a three dimensional portrayal of him as only the public record remains. Nevertheless Harron does a good job of giving depth and colour to his subject. In any case, it might be argued that the buildings he left behind give us an insight into Barre’s character: bold, imaginative, intricate, wide ranging and complex.

In this study, Harron spends one chapter on the biographical details and four in thematically examining Barre’s work.

Crossing divisions

At a time of sectarian tensions in Ulster, Barre was remarkable in crossing the religious divisions and he was asked to design churches and other buildings for the Church of Ireland, Methodists, Presbyterians (Subscribing and Non-Subscribing) and Catholics, which was a rare achievement at the time.

The other area that he was prominent in was memorials and civic work. This included Belfast’s Albert Memorial Clock and the Ophthalmic Hospital. Although special mention should be given to the Crozier Memorial in Banbridge, Co. Down.

This is a tribute to an Irish polar explorer who was lost with Franklin’s 1845 expedition to discover the North West Passage. This imposing monument is conventional in design – a statue of Francis Crozier in heroic pose above a pedestal – except for the inclusion of four polar bears atop the buttresses supporting the structure.

This raises an ordinary monument into something exceptional and shows the degree of imagination (and perhaps wit) that Barre possessed.

Domestic and commercial work

Barre was also at ease with domestic and commercial work. He designed a number of grand houses for the wealthy of Ulster such as The Moat in Belfast, Bessmount, Tyholland, Co. Monaghan, and Roxborough Castle, built for Lord Charlemont in Co.Tyrone.

In his commercial work, Barre could bring both flair and utilitarianism. His flair can be seen in the former Provincial Bank in Belfast, described by Harrron as a “Romanesque-cum-Neo-Palladian two-storey palazzo”.

In contrast, Edenderry Flax Spinning Mill, while a huge imposing building on the Crumlin Road, Belfast, is almost austere in comparison (although it does have some elaborate details) being designed for a mainly utilitarian purpose.

Excellent study

This is an excellent study of one of Ulster’s most important nineteenth century architects, whose legacy is often overshadowed by his great rival, Charles Lanyon.

While I knew of Barre’s works in Newry, it was not until reading this book that I became aware that he was also responsible for so many significant buildings in Belfast and elsewhere.

He achieved a lot in his short life and one is left wondering what else he may have achieved had he lived for as long as his great rival. This is a book that will appeal to anyone interested in the architectural heritage of Ireland and sheds light on the career of this remarkable architect.