No Jigs or Reels

Tony Canavan looks at the Irish angle of Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time,

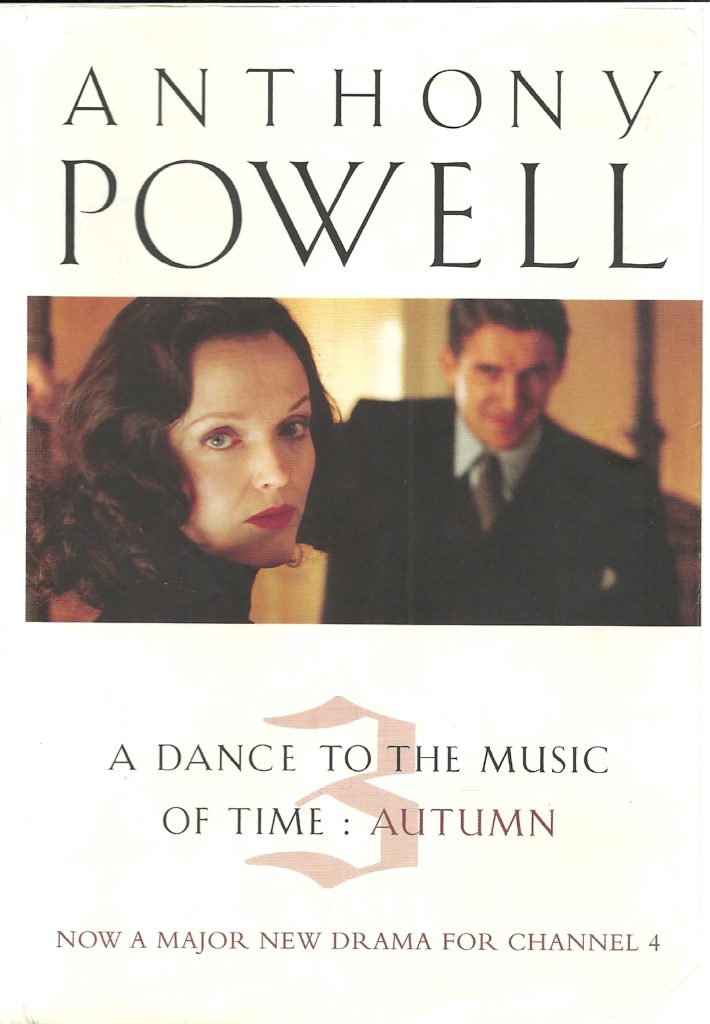

Anthony Dymoke Powell (1905 –2000), to give him his full name is regarded by many as the quintessential modern English novelist. He is best known for his saga of 20th century Britain, A Dance to the Music of Time, published between 1951 and 1975, which can be seen as an English equivalent to Tolstoy’s War And Peace, although with considerably more humour. The twelve novels in Powell’s saga cover a wide sweep of British history, taking in not just the personal stories of his protagonists but also major events and social developments. A Dance to the Music of Time has remained in print continuously and has been the subject of TV and radio dramatizations. In 2008, The Times named Powell among their list of The 50 greatest British writers since 1945, while Time magazine included it in its TIME 100 Best English-language Novels from 1923 to 2005.

Despite (or because of) his Englishness, Powell’s ultimate origins were Welsh and he had Irish connections. He was married to Lady Violet Pakenham (1912–2002), sister of Lord Longford. This marriage gave him an entrée into the upper echelons of British society and involvement with this well-known Anglo-Irish family, represented as the Tollands in the novels.

The title, A Dance to the Music of Time, was inspired by the painting of the same name by Nicolas Poussin. The story is an often comic examination of English political, cultural and military life in the mid-20th century. Each volume is narrated by Nick Jenkins in the form of his reminiscences, beginning with his early education and going up to his old age. Just as much of the action of the novel is based on actual historical events, so too most of the characters are based on real people that Powell knew or was related to. For example, Erridge, Earl of Warminster, is based on his brother-in-law, Lord Longford, and Sir Magnus Donners is largely inspired by Lord Beaverbrook.

The third volume in the series, Autumn, consists of three novels set during World War II, during which, Powell served with the Welch Regiment and later in the Intelligence Corps. Again based on Powell’s own experiences, there is an episode set in Northern Ireland in the first part of this trilogy, The Valley Of Bones. Although the names of the different locations have been changed, anyone familiar with the geography of Northern Ireland can work out their actual equivalents. Most of Jenkins’ time is spent in Co. Armagh and the castle his regiment is billeted in is identifiable (I think) with Gosford Castle outside the Armagh town of Markethill, while the canal that features in the military manoeuvres must be the Newry Canal.

Away from the theatre of war, this posting consists mostly of drills, training exercises and the personal conflicts and rivalries among the officers. Lt. Jenkins, our narrator, is not much impressed by Northern Ireland or the Irish in general. The place is certainly a foreign country to him and his fellow Welsh soldiers, described as “bare, dismal country, wide fields, white cabins, low walls of piled stones, stretches of heather, more mountains far away on the horizon”; and they find they have little in common with the locals. The soldiers are warned from the beginning that not all of the native population are in favour of their presence and some are actively pro-German. Jenkins and his fellow officers are told, “A few miles away from here, over the Border, is a neutral state where German agents abound. There, and on our side too, elements exist hostile to Britain and her Allies. There have been cases of armed gangs holding up single soldiers separated from their main body, or trying to steal weapons by ruse.” This refers to the Irish republic and the activities of the IRA.

Jenkins takes a dim view of the Unionist population who are generally portrayed as dour and dull, and not exactly pulling their weight with the war effort. On the other hand, he does not have a high opinion of the Catholics either who, although more interesting, are portrayed as being feckless and untrustworthy. In truth the locals do not appear as major characters in the story, apart from one exception, Maureen, a flirtatious barmaid, whom Captain Gwatkin loses his heart to. However, despite Maureen’s charms, Northern Ireland does not do well out of Powell’s novel.

Tony Canavan, Consultant Editor Books Ireland