Tony Canavan looks at Eric Ambler’s unusual villain

THE IRISH ANGLE

Eric Ambler (1909–1998) was an influential English author of thrillers, who took the genre invented by John Buchan, of the plucky English amateur taking on foreign villains, to a new level. His spy novels in their tone and realism influenced the likes of Graham Greene and John le Carré. However, unlike many of his contemporaries, Ambler was left-wing and in his novels the bad guys are Fascists and Big Business, while Soviet agents and trade union activists are the good guys. While he became disillusioned with the Soviet Union, he did not abandon his principles although his post-War novels tended to avoid politics.

Ambler is probably best known through the films that were made of his novels, notably The Mask of Dimitrios (1939) which was turned into a film in 1944 featuring Orson Welles. Others include Epitaph for a Spy, which was filmed as Hotel Reserve (1944) starring James Mason, Journey into Fear (1943), starring Joseph Cotten, and Background to Danger (1943), based on his Uncommon Danger, starring George Raft. Although his most successful film adaptation was the 1964 heist movie, Topkapi, adapted from his The Light of Day.

The heroes in Ambler’s 1930s novels are usually amateurs, Englishmen abroad who find themselves drawn into a plot involving criminals, revolutionaries and spies. At first bemused and then angered by what is happening to them, their intelligence and strength of character see them through, sometimes with the help of an actual spy. These spy novels evoke the atmosphere of the times with demagogic leaders stirring up xenophobia, international instability, and people displaced by conflict and oppression. His writing is populated by characters who assume identities in order to survive, exiles and misfits. This all makes them very relevant today.

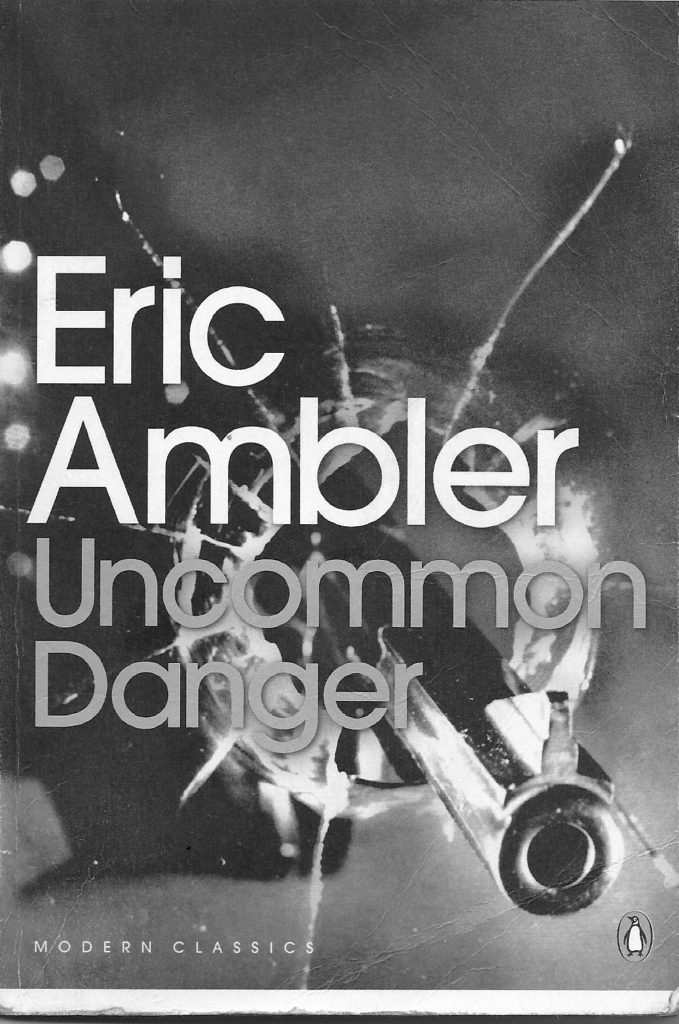

Ambler’s second novel was Uncommon Danger, published in 1937. Kenton, a freelance journalist down on his luck, gets involved in a plot to provoke hostilities between the Soviet Union and Romania, forcing the latter into an alliance with Nazi Germany. Desperate for money, he undertakes to smuggle some documents from Germany into Austria, but his employer is found dead and Kenton is accused of his murder. Wanted by the police, he is also pursued by a gang of thugs for whom the documents were originally meant. He finds unlikely saviours in Andreas and Tamara Zaleshoff, KGB agents, who eventually clear his name and thwart their enemies.

This is not one of Ambler’s best novels; it is clear that he is still developing his art. The plot is fairly simple but with enough car chases, fights and torture scenes to keep you turning the page. Kenton is an engaging hero (or anti-hero) and having two Soviet agents as protagonists is intriguing. Ambler spells out his political leanings in the novel. While other thriller writers were fixated on Jewish and Communist conspiracies, Ambler makes it clear that Capitalism is the real villain. Early on in Uncommon Danger, he writes: “It was the power of Business, not the deliberations of statesmen, that shaped the destinies of nations. The Foreign Ministers of the great powers might make the actual declarations of their Governments’ policies; but it was the Big Business men, the bankers and their dependents, the arms manufacturers, the oil companies, the big industrialists, who determined what those policies should be.”

Interestingly there are two Irish angles to Uncommon Danger. The first is that Kenton’s father was born in Belfast and his mother came from Brittany which makes him an uncommon sort of Englishman. However the more significant Irish connection is related to the War of Independence and, given recent controversies over songs and chants, is quite relevant today. While the chief villain is a mercenary in the pay of a big oil company, a Russian posing as Colonel Robinson, his henchman is Captain Mailer, a former Black And Tan. He is a perversion of the usual English hero in that although he is an officer and a gentleman, from the outset it is made clear the Mailer is an evil sadist. He despises foreigners and revels in mayhem. Mailer delights in using a rubber truncheon on Kenton to get him to talk. It will be no surprise that he comes to a bad end.

What is interesting is that Ambler simply states that Mailer was a Black And Tan. He feels no need to explain that this force was part of the RIC, or that it acquired an unsavoury reputation for brutality and violence in the Irish War of Independence. Although the novel was written fifteen years after that war, Ambler could safely assume that his British readership would remember the events of those years and the role played by the Black And Tans. If in Chandler’s The Big Sleep, Rusty Regan was an off-the-peg hero requiring no in-depth exposition or backstory, so then Mailer, as a Black And Tan, was an off-the-peg villain requiring no in-depth exposition or backstory for any reader in 1937. Perhaps worth remembering when considering commemorations of the War of Independence.

Tony Canavan, Consultant Editor Books Ireland