THE IRISH ANGLE

Tony Canavan finds an Aboriginal detective at home among Irish outlaws

Born in England, Arthur William Upfield (1890–1964) moved to Australia in 1911 and served with the Australian Army during World War I. For the next twenty years he travelled throughout Australia, working at a number of jobs, including as a cattle drover, rabbit trapper and cattle station manager. During the course of his travels he learned about Aboriginal culture and later used the material he had gathered in his novels, eventually finding a publisher in 1951. In fact, Upfield was bitter that the Australian public ‘would read any tripe from abroad’ but would not support Australian writers. Despite this, his novels featuring Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte were a commercial success and he lived in comfort in New South Wales until his death in 1965.

He became involved in a real-life murder case following publication of The Sands of Windee in 1961, a story in which Inspector Bonaparte comes up against a ‘perfect murder’. In the story, the murderer invents a method for destroying evidence of the crime. Upfield’s ‘Windee method’ was used in the Murchison Murders, and because Upfield had discussed the plot with friends, including the accused man, he was called to give evidence in court.

Detective Inspector Napoleon ‘Bony’ Bonaparte, a mixed-race Indigenous Australian, in the Queensland Police was Upfield’s most successful creation. The books were the basis for a 1970s Australian television series, Boney, as well as a 1990 telemovie and a 1992 spin-off TV series. Upfield said that he based Bony on a man known as ‘Tracker Leon’, a mixed-race Aboriginal employed as a tracker by the Queensland Police. There is apparently no documentary evidence, however, that such a person existed.

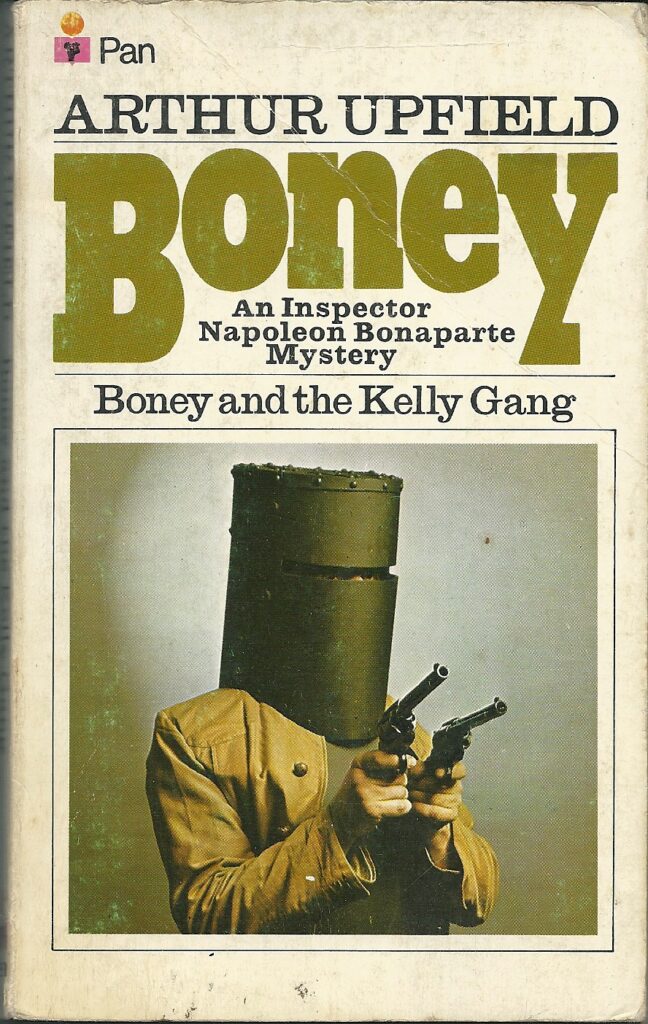

Bony and the Kelly Gang was originally published in 1960 and reissued a number of times. Hidden in the mountains of New South Wales, Cork Valley is home to a clan of Irish outlaws. When an Excise Officer, looking for illicit distilling, is murdered, Bony is given the job of finding the killer. Disguised as a horse-thief, the half-Aboriginal detective hitchhikes into the valley. There he finds it populated by an Irish clan, of two branches, the Kellys and the Conways. Bony is taken in by the Conways and is soon one of their number. He overcomes the initial hostility of the Kelly patriarch, Red, and is invited to join the Cork Valley smuggling operation.

Bony is charmed by the Cork Valley community from the start and feels at home there. He is puzzled at what motivates their illegal activities since they don’t need the money. He discovers that they have a political creed of their own, which is opposed to corrupt politicians and promotes individual freedom. They hold up the outlaw Ned Kelly as a hero and even have an annual festival in his honour. Upfield devotes almost four pages to a speech given by Red Kelly at the festival, in which he articulates the political philosophy of the clan.

The portrayal of the Irish in the novel is on the whole positive. Their illegal activities are an act of rebellion and beyond that they prove themselves to be generous, open-hearted people. Individual traits, good or bad, are not blamed on race but on individual character. Upfield shows, too, that the Irish in Australia are also on the side of law and order. The two policemen working with Bony are Casement and O’Leary, while the Cork Valley Irish acknowledge that the regional and federal governments are full of Irish politicians.

On the whole, Upfield avoids the usual clichés when describing the inhabitants of Cork Valley. Some do speak with a brogue, which is rendered phonetically, and one of the women is described as ‘a dark Irish beauty’. The ancient matriarch of the Conways speaks ‘Gaelic’ and has fond memories of Ireland. The nearest we come to a disparaging comment is when someone is described having ‘a face like the proverbial Irishman depicted in Punch’.

Perhaps, the most significant thing is that the Cork Valley people are blind to Bony’s race. Bony is at home among them and for a while even forgets that he is there to capture a murderer. At one point, when surrounded by the Kellys and Conways, he reflects that for the first time in his life, he is ‘free from the colour bar’. Despite his conflicted loyalties, Bony brings the murderer to book, and manages to persuade the Kellys and Conways to give up their illegal activities. The novel ends with him being invited back to their next Ned Kelly festival.

More often than not in this column, I end up deploring the largely negative or two-dimensional portrayal of Irish characters. Unlike, say, John Buchan or Arthur Conan Doyle, however, Upfield gives a rounded portrayal of the Irish. He may stray close to the ‘benevolent’ cliché of the wistful, musical Irish but he also depicts the downside to his characters and negates stereotypes by showing that the Irish are found in all walks of life. In that, he is a refreshing voice. Bony and the Kelly Gang is a good read but it is also noteworthy for the portrayal of its Irish characters.

***