In this excerpt from The Irish Defence Forces, published by Four Courts Press, Eoin Kinsella discusses the efforts of the Army Organization Board and the Temporary Plans Division to modernise the Irish Defence Forces in the late 1920s.

by Eoin Kinsella

By early 1925 it was clear that the Irish Defence Forces had weathered the storm of demobilization. For the first time since January 1922, following civil war, large-scale demobilization and the Army Mutiny crisis of 1924, time and space were available for a comprehensive review of the state’s defensive needs.

Peadar MacMahon’s tenure as Chief of Staff (March 1924 – March 1927) was characterized by an expansive approach to reform. Following a conference with his General Staff in April 1925, MacMahon convened an organization board, with a remit to advise on the modernization necessary ‘to fulfil the functions of a modern army in relation to national defence’.

A firing party from An Chéad Chath under the command of Lt Seán O’Connor, accompanied by buglers, during a ceremony on 21 August 1927 to commemorate the deaths of Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins. More than 4,000 troops assembled at McKee Barracks before parading to the ceremony, which took place on the lawn of Leinster House in front of the Collins-Griffith Cenotaph – a concrete covered wooden structure unveiled in August 1923 that contained plaster medallions of both men. The National Army played an important role in symbolically projecting the legitimacy of the Irish Free State during the 1920s, particularly at sites such as Bodenstown, which continued to be a focal point for republican opponents of the Treaty and of the Free State. An Céad Chathlán Coisithe (1 Infantry Battalion) was established on 10 March 1924, with recruitment initially confined to fluent speakers of Irish, preferably from a Gaeltacht area – a policy that continues in operation to this day.

Defence policy

To do so effectively, some indication of the government’s defence policy was required. In July 1925 the Council of Defence presented a memo to the government, outlining the ‘urgent and absolute necessity’ of providing the council with ‘at least the outlines’ of a defence policy.

The memo warned that not only were the Defence Forces entirely dependent upon the British government for equipment, they were incapable of providing any effective defence against a modern army, navy or air force. In the event of war between Britain and another powerful nation, Ireland was likely to become a ‘cockpit for the belligerents.’

A Defence Forces soldier pictured in regulation drill dress, with 1908 pattern webbing and Lee Enfield rifle. This was one of a series of photos of the various uniforms of the National Army, taken by Training and Operations Branch on the grounds of General Headquarters, Parkgate Street, in the winter of 1924/5.

Commitment to neutrality

Assuming that the state would remain neutral in any international conflict while preventing the use of its territory to attack Britain, the council proposed developing forces ‘sufficient of a hornet’s nest to any outsider’ to deter invasion. Three main policy options were offered for the government’s consideration:

- the development and organization of Irish military resources into a complete defensive machine, including aerial and naval capabilities, and the fostering of industrial capacity to manufacture military equipment;

- the development of Defence Forces which would be an integral part of the British Imperial forces and would, in the event of war, be controlled by the Imperial General Staff;

- complete reliance on Britain for defence from external threats, and the maintenance of Defence Forces solely to deal with internal threats.

The government’s response, delivered in November, was to confirm its commitment to neutrality. The Defence Forces were to consist of between 10,000 and 12,000 all ranks and be capable of ‘rapid and efficient expansion’ in time of need.

Problems

In addition to an ability to defend the state’s territorial integrity against internal or external aggression, the Defence Forces were to be ‘so organized, trained and equipped as to render it capable, should the necessity arise, of full and complete co-ordination with the forces of the British government in the defence of Saorstát territory.’

The brief document merely sketched the outlines of a defence policy, but at least offered a framework around which the Defence Forces could plan.

Problems arose immediately. Rapid expansion implied reserve forces, which would not be organized for another two years. The practicalities of effective co-ordination with British forces, either from a military or political perspective, were not specified.

While the Anglo-Irish Treaty stipulated that a joint conference on coastal defence should be convened by the end of 1926, neither government was inclined to press the matter and the conference never materialized. A handful of spaces were made available for officers to attend courses each year at British military schools and colleges, but such courtesies were a long way from active co-operation.

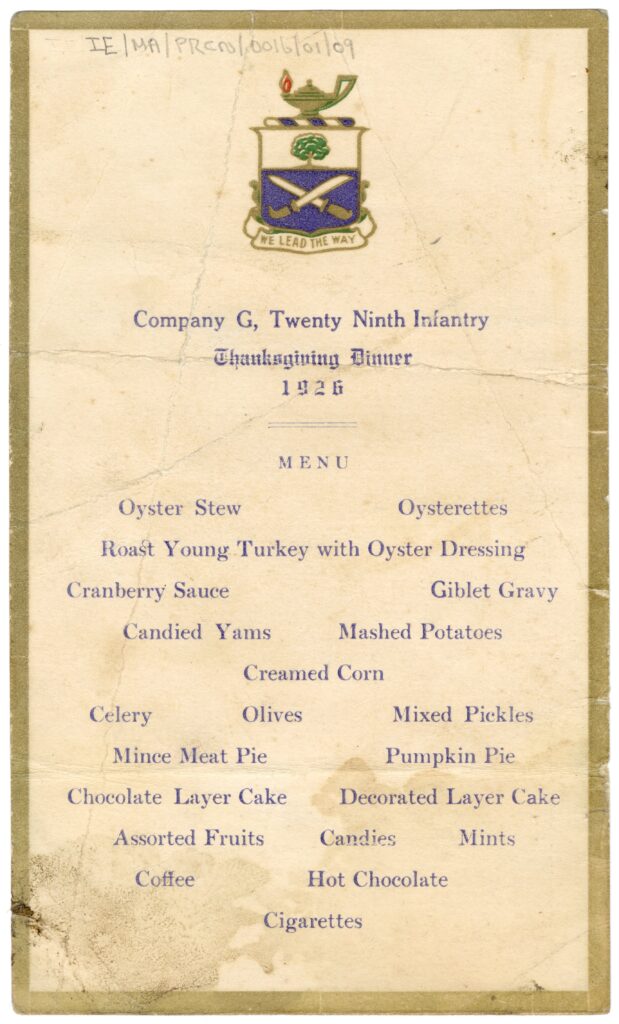

Menu for the Thanksgiving Dinner hosted by Company G, 29th Infantry of the United States Army and attended by Lt Seán Collins-Powell while on the Military Mission to America.

Structural review

The Army Organization Board received submissions from every corps and service, as well as staff and technical officers, and reviewed the structures of various other military forces.

Delivered in June 1926, its report recommended the conversion of the Defence Forces ‘from its present semi-immobile basis, designed to deal with internal disorder solely, to a mobile basis’.

A volunteer force and reserve officer corps would be necessary to supplement the regular army, which would provide a ‘skeleton or scaffolding from which the main body of the Defence Forces would be built up in time of war’.

Military mission to America

In an effort to broaden the General Staff’s knowledge of military matters beyond its familiarity with British systems, and to expand on the Board’s work, the government sanctioned the departure of six officers on a military mission to America.

Their remit was to conduct a general study of the legislation governing American defence and its military system, with a particular focus on military education.

First mooted in 1925 but delayed by scepticism from several quarters, including the Department of Finance, the mission proved to be an important milestone in the modernization process, particularly the subsequent establishment of the Military College.

Assistant Chief of Staff Maj Gen Hugo MacNeill and Col Michael J. Costello were first to depart, in July 1926, followed by Maj Joseph Dunne, Capt Patrick Berry, and Lts Seán Collins-Powell and Charles Trodden a month later.

There was palpable excitement at the mission’s potential for shaping the future of the Defence Forces: ‘For the first time in our lives we will be able to estimate exactly on our requirements in accordance with a definite programme.’

All returned in October 1927, having studied tactics and troop dispositions at Fort Leavenworth, Fort Benning and Fort Sill and completed tours of inspection of several other American military schools and installations.

Pictured here during the Emergency, the Muirchú was the main vessel of the Marine Service during this period. Better known to history as the Helga, the British ship that shelled Dublin city during the Easter Rising, the Muirchú first entered service for the Coastal and Marine Service in 1922, before being transferred to the Department of Agriculture in 1923. It was recommissioned in the Defence Forces in January 1940. Its 12-pdr gun is visible on the foredeck.

Temporary Plans Division

Shortly after their return, the Temporary Plans Division was established at the Hibernian Schools, Dublin, with MacNeill as director and a staff of fifteen officers, including Costello.

Structured as an experimental general staff, the division was presented with an ambitious brief: to devise a doctrine of war that would form the basis of the state’s defence policy; to formulate tactical doctrines to govern the deployment of the Army and its corps in line with that policy; to propose a suitable organization and devise tables of equipment and supply; and to outline the best methods for educating officers and men on the doctrine of war.

Its work commenced on 6 February 1928 and was completed the following year. Daniel Hogan, who replaced Peadar MacMahon as Chief of Staff in 1927, was cautiously optimistic that, given time and resources, the division’s recommendations could transform the Defence Forces.

Increasing confidence

The Division’s proposals on military doctrine were endorsed, though it generated some internal opposition with its recommendation to adhere closely to British doctrine. In reality there was little alternative, given the government’s previous indication of its preferences, the state’s reliance on Britain for virtually all its military supplies, and the British government’s willingness to facilitate training of Irish officers.

The cost, both financial and political, of pursuing closer links with the American or any other military were simply too high.

On a technical level, the work of the Army Organization Board and Temporary Plans Division demonstrated the increasing confidence and professionalism of the General Staff.

Submission of the Division’s final recommendations in 1929 marked the end point of nearly four years of continuous study, during which a plethora of plans and advice were presented to the Minister for Defence. Many were simply too ambitious, paying no heed to the economic and political realities that prevailed. Virtually all were ignored, or accepted but later quietly shelved.