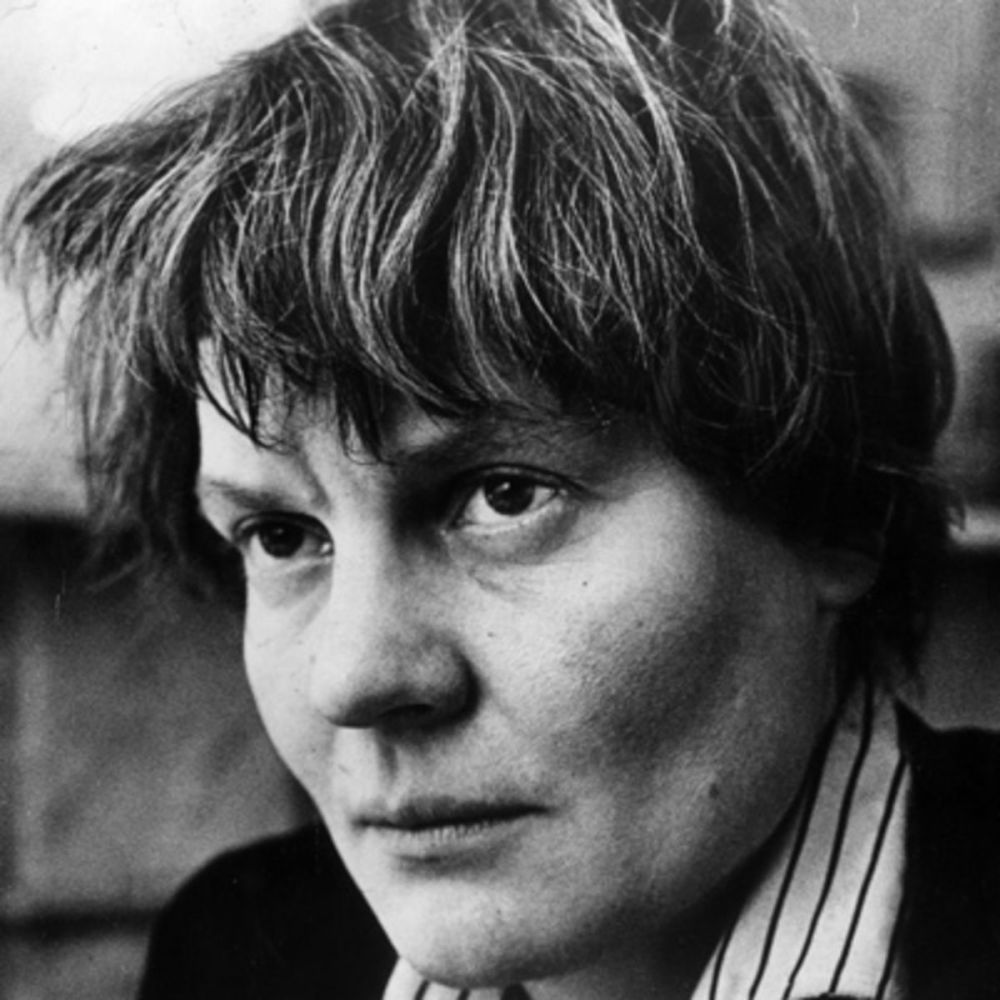

Marking her centenary, Miles Leeson discusses Iris Murdoch and Ireland

Iris Murdoch has had a complicated relationship with Irish literary criticism. Until recently, if she was mentioned at all it was in relation to her friend Elizabeth Bowen, or as a figure who merely claimed a vague relationship with Ireland. In reality, she was from Anglo-Irish stock and could be angry if accused of not being a ‘real’ Irishwoman: ‘people sometimes say to me rudely, “Oh, you’re not Irish at all!” But of course I’m Irish. I’m profoundly Irish and I’ve been conscious of this all my life, and in a mode of being Irish which has produced a lot of very distinguished thinkers and writers’. Among those thinkers and writers she would claim Yeats, Bowen and an early reading of Samuel Beckett’s Murphy, which infused her first novel, Under the Net (1954). Yet her relationship with Ireland is a complex one.

Murdoch was born in Dublin in July 1919 to Hughes, a civil servant from the North, and Rene, an aspiring opera singer: an only child in, as she would later recount, ‘a perfect trinity of love’. Although her parents moved to London when she was only a few months old, Murdoch would regularly return to visit family, and some of her earliest memories were of summer holidays spent with her cousins in Dún Laoghaire. At home in London, her parents made sure they did not assimilate into English life. As her biographer, Peter Conradi, put it in Iris Murdoch: a life (2001), she had ‘a lifetime’s investment in Irishness’.

The author of 26 novels, Irish characters—although not with any regularity the landscape of Ireland— would feature in her work throughout her career. There are only two novels set wholly in Ireland: The Unicorn (1963), which focuses on two large houses on the barren Burren (the Scarren in the novel) in west Clare, and The Red and the Green (1965), her only political novel, set in Dublin around the 1916 Easter Rising. For those new to Murdoch, The Unicorn is certainly the best of her Irish writing.

The Unicorn tells the story of a young woman, Marian Taylor, who, as the novel opens, has just arrived at a desolate railway station at an unnamed location on the coast. She has answered an advertisement for a governess, but she soon discovers that it is not a young girl whom she is there to educate and entertain, but a woman slightly older than herself who is secluded in her room. She joins a household who are either there to protect or imprison the mistress, Hannah Crean-Smith. As in many Murdoch novels, a central character experiences a form of enlightenment, a stripping away of the ego. This happens to the self-absorbed Effingham Cooper who is in love with Hannah and is an inhabitant of Riders, the ‘big house’ that faces Hannah’s Gaze Castle. He walks out alone at night and stumbles into a bog and begins to sink. As he does so, he confronts his own mortality:

Since he was mortal he was nothing and since he was nothing at all that was not himself was filled to the brim with being and it was this that the light streamed. This then was love, to look and look until one exists no more, this was the love that was the same as death. He looked, and knew with a clarity which was one with the increasing light, that with the death of the self the world becomes automatically the object of a perfect love. He clung on to the words ‘quite automatically’ and murmured them to himself as a charm.

This concern with the negation of the self leads her characters, who experience moments like this, Effingham included, to a more perfect form of loving attention to others. If there is one central feature of her fiction, it is the movement from moral blindness to a perfecting of love and The Unicorn is certainly a novel that displays this.

There is also the short story Something Special (1957) set in Dún Laoghaire. Although generally considered one of the completist, it has been suggested that the characters resemble members of her own family. A tale of claustrophobic family life and the yearning of a young woman to escape to the city, it is certainly worth an hour of anyone’s time. Not having lived in Ireland, however, she could not produce a work resembling Bowen’s memoir Seven Winters: memories of a Dublin childhood. Murdoch and Bowen became close later in Murdoch’s life and she was invited to Bowen’s Court (near Kildorrery, now demolished) at least twice in the 1950s, just as Virginia Woolf had been years before.

So why the reluctance for some to claim her as part of the Irish literary tradition? Certainly, location plays a part in this. After her teenage years she would rarely return and was certainly rather evasive about the existence of her living relations in interviews. It is also fair to say that whenever Ireland, or the Irish, appear in her novels, they often appear romanticised, or at least idealised in some way. She herself recognised that her claims to Irish nationality could be perceived as sentimental. On the one hand she wanted to draw close to it, and yet she worried about romanticising its tragedy, or making Ireland into a land of fantasy. Shortly after the publication of The Red and The Green, the Troubles recommenced in earnest and she did not trust herself to be rational about Ireland, frequently being moved to tears by the plight of those suffering or losing her temper at the news. She became so disillusioned with republicanism that she became an open supporter of Ian Paisley; yet by the end of the 1970s she was outraged by the cruelty on both sides.

Although these mixed feelings continued for some time, she was delighted to be awarded an honorary degree from Trinity College Dublin in 1985, and wrote afterwards in a letter that ‘I sometimes reflect on how my life is touched by constantly thinking about Ireland’. This constant thinking did not manifest itself into more novels about Ireland but her later novels do contain some of her most striking Irish characters that embody some of their creator. It is through these characters, rather than the small number of works set in Ireland, that we get the fullest sense of her Irishness. The first of these is Finn in Under the Net, a ‘humble and self-effacing person’ who acts as a foil to Jake, the central protagonist. At the end of the novel Finn returns to Ireland: ‘He just wanted to go home I suppose … and there’s always religion’. And there are many other examples.

Even at the end of her life, when Alzheimer’s disease had robbed her of so much, the last thing she could recall, even after she had forgotten she had been a novelist, was the fact that she was Irish. It is fitting then that a plaque is to be installed at the place of her birth, 59 Blessington Street, and that An Post is releasing a commemorative stamp— both on the 15 July this year. On her centenary, picking up a copy of The Unicorn would not be a bad place to start.

Miles Leeson is director of the Iris Murdoch Research Centre at the University of Chichester, England.

First published in Books Ireland July/August 2019.