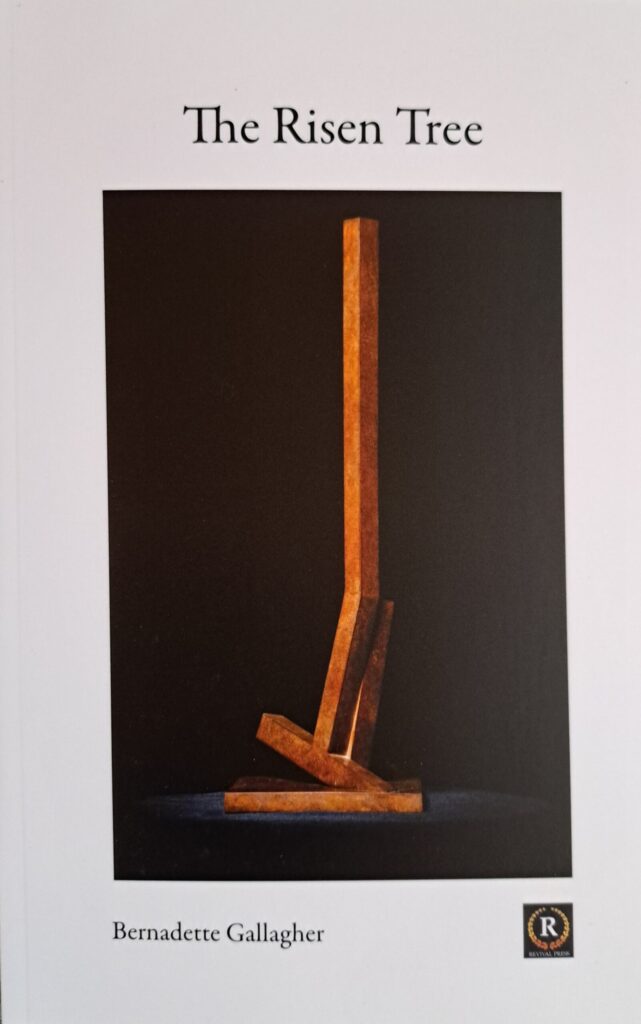

The Risen Tree|Bernadette Gallagher|Revival Press

We write to find out, to question—The Risen Tree, by Bernadette Gallagher

by Orla Fay

Each poem in The Risen Tree by Bernadette Gallagher is a meditation on a Psalm. This is a collection about the possibility of life overcoming death, about memory, mortality, and morality. The title poem opens the collection:

I think of all the dead below us

feeding us

sustaining us

wanting us to go on.

Throughout, the poet questions mortality; the final poem, ‘Lifeline’ stoically accepts that death is a part of life, as much as birth:

The man who is near to death

knows there is no going back,

no better.

Imagine delaying a birth.

The epigraph from Sappho might seem grim or gloomy but it may just be the poet’s acceptance of the passing of us all into oblivion as ‘dim shapes. Having been breathed out.’ It was believed to be a chastisement by Sappho of a noble woman who had no time for creativity.

Dead you will lie and never memory of you

Will there be nor desire into the aftertime — for you do not

share in the roses

of Pieria, but invisible too in Hades house

you will go your way among dim shapes. Having been breathed out.

Gallagher describes it as a ‘trigger for a journey through days, seasons, years…these fragments become a distillation of the poet’s life.’ If we are to take her at her word, then we must examine the book as a series of fragments. Each piece in the collection is followed by a blank page and this space forces us to read even more carefully.

The cover image Antigone, a bronze sculpture by Michael Warren, is a solid, earthed, and upstanding piece. Land and nature are crucial in this collection, and in ‘The Life of a Fly’ Gallagher looks to the natural world for comfort:

Today I want to see what I see

my thoughts of evil-doing by gods

and man are too easy to conjure up.

Similarly, it is the miniscule in nature that pricks the poet’s conscience in ‘To Fail is to Live.’ A bug removed from a glasshouse and thrown on the grass while being unable to remove another two causes the poet to reflect ‘on what I had done – separated a parent from their young.’

Agriculture is found in the woods, the tomatoes, the animals of the collection. We find blackbirds, thrush, robins, crows, and deer. In ‘Winter Food’ it is noted that ‘All these dead things will become compost,/sustain new life.’

School is a strong feature of the past in the collection, and a source of disillusionment for the poet. In ‘Legacy’ the child learned about shame/náire and the ‘sting of rulers not used for measuring.’ In ‘Hell on Earth’ we are brought ‘back to those days you hated.’ In ‘The Myth of Mankind’ Gallagher says ‘I turn away from truth, don’t want to hear/how men abuse.’ ‘The Dark Side’ describes the weight of keeping secrets:

Keeping secrets is a burden – even a mule

would falter if its back were so weighed down.

Spirituality is of course evident in the collection. The Book of Psalms, from the Old Testament, is a collection of 150 ancient Hebrew poems, songs, and prayers that come from different eras in Israel’s history that praise God. In ‘The One Within’ an omniscient presence is ‘the wind and the rain,/the air,’ and ‘the voice on the phone, in my ear,/in my head, as I sleep, when I awaken.’ While in ‘Morning Light’ the poet questions a faith but also wonders about scientists who ‘search, find ways/to change our lives,/to look into the void,/black holes where heather does not grow.’

The stars make gorgeous appearances in ‘The Middle Path’ where Gallagher writes:

Sometimes we reach for the Heavens to find darkness

and from the depths of hell we find light.

And in ‘Sixth Sense’:

To pull back the curtains of gauze

and glimpse into an ocean of stars.

To know we are not alone when we are alone.

Perhaps the crux of the book is found in the arguments posed in ‘Caress my Brow’ and ‘A Moonless Night.’ In the former the poet asks us, ‘Who remembers us, if not prompted,/left alone they will not recall.’ While the latter calls to the ancestors and the Psalms themselves which have survived through being written down: ‘Words on the page or spoken or sung.’

The question is, can art overcome the transience of life? I am not entirely sure what Gallagher herself thinks, you will have to ask her, or draw your own conclusions from the collection. What is certain is that we are all here in the human condition. In ‘Today’s Lesson’ we are wisely told to forgive.

This is a finely thought out and executed collection. Each piece contains a weight of contemplation and, like a bell ringing, leaves its vibration with waves that spread out in the reader’s mind.

The Risen Tree is a collection of great depth and ambition. It has certainly left an impact on me and caused me to reflect and question. I have thoroughly enjoyed the direction in which the book has taken me. Bernadette told me when I asked what her main themes were, that we write to find out, to question. She has certainly achieved this with The Risen Tree.