Caitríona Ní Chléirchín writes about her latest collection of bilingual poems

“To be translated involves another level of vulnerability, which allows great room for creative exploration and possibility.”

As an Irish-language poet, to be translated means to have become visible to a wider audience. Being visible brings with it recognition, which gives hope to the poet that what she says is heard. And to be heard is a fundamental human need. I choose to write in Irish because it is in this language that I find my poetic voice and am able to truly express my creative being.

Writing poetry for me is about translating emotion and experience into language. Most of the time our experiences of love and loss elude language altogether, but in the chasm between language and emotion, poetry happens. Writing in the first instance involves vulnerability, opening up the inner core of being and psyche to the reader. To be translated involves another level of vulnerability, which allows great room for creative exploration and possibility.

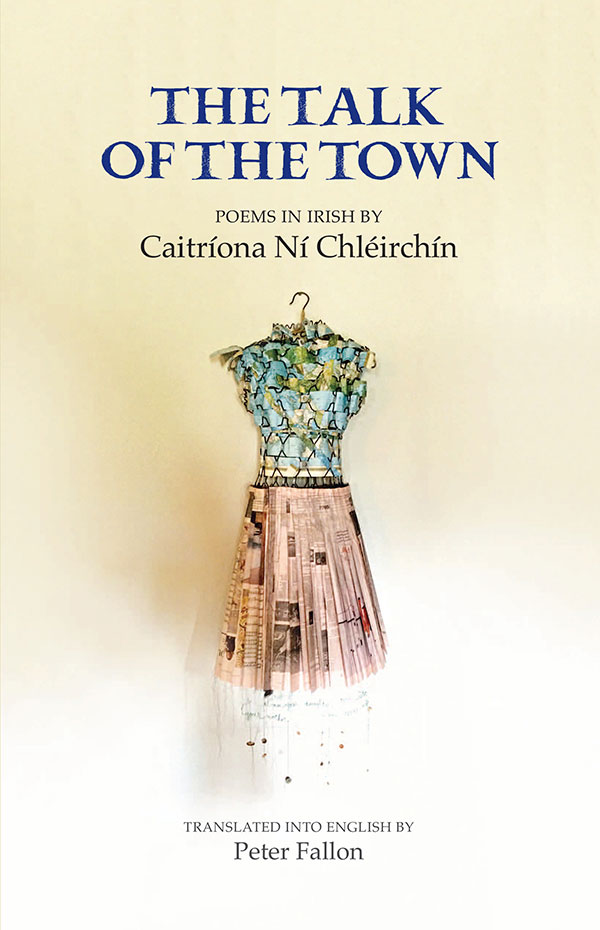

The Talk of the Town includes work from my previous collections Crithloinnir (2010) and An Bhrídeach Sí (2014), poems from Calling Cards and some new poems. I am speaking in this collection about my experience as a woman and giving voice to female experience like many of the best modern writers in Irish who have influenced me, like Máire Mhac an tSaoi. I am acutely aware of how women’s voices have been silenced for centuries and their identities continue to be taken away from them.

The question of gender is important when it comes to translation, I believe. Are we not always already translating ourselves, as women, as people, as poets? Fallon approached the challenge of translating a feminine poetic voice with sensitivity, elegance and respect. He also navigated carefully and wonderfully the fraught landscape of linguistic tension between the Irish and English languages, given the postcolonial aspect of that relationship.

I have attempted to give new voice to female personae from Irish history and the literary tradition, such as Caitríona, the countess of Tyrone, wife of Hugh O’Neill, during the Flight of the Earls in my poem ‘Scaradh na gCompánach’. Her voice is absent from history and I was interested in exploring her sense of intuition and foreboding at having been forced by her husband to leave her five-year-old son behind her and board the ship.

Throughout the book, I am speaking about the emotional complexities of loss and Irish is the perfect language to express the depth and resonance of multiple losses and traumas. I was particularly moved by Fallon’s translation of ‘Capall Bán’ to ‘The Old Grey Mare’, which captures the wonderful transformative possibilities through translation.

When faced with the common dilemma of how to translate Irish place names, Fallon is once again both understanding and ingenious. He understands when to capture the sound in the litany of place names: ‘I went out to find you in Derrygassan, in Derryshillagh, in Derryhee and in Dernashallog’ and when to capture the meaning, and often succeeds at both. Fallon understands the love of the landscape, the land, the place names and how I use the folklore and myth of my native area to show my love for this haunted landscape. Fallon translates my poem ‘Cluain na hEorna’ to ‘Barley Aftergrass’, allowing the reader to taste the rich light of the barley meadow where the fairy bride is furtively making her way.

I grew up along the border in Gortmoney near Emyvale in County Monaghan at the height of the Troubles. As children, we often crossed the border at Auchnacloy, with my mother driving when we were journeying to visit my grandmother in Tyrone. We thought it was completely normal to be stopped and searched and asked to step out of the car and questioned by soldiers at the checkpoint. We were not immune, however, to my mother’s terrible anxiety and the importance of not saying the wrong thing to an armed soldier with three young children in the car.

In his translation of my/the series of poems ‘Trasnú na Teorann’/‘Border Crossing’, Fallon perfectly captures that sense of tension, unease and anxiety. Crossing over from Irish into English, he leaves a physical space, where another translator might have written ‘nothing’. ‘Whatever you say, say .’ I am very moved by his translation of ‘Tost’, which captures all the intimacy and violence language that a poet who grew up along the border experienced in terms of stories untold, codes of silence and ‘differing ways of telling a tale’. Maybe it was this emphasis on being silent and saying nothing when I was growing up that made me (want to find a voice as) a poet.

I would like to thank the Gallery Press for publishing my first bilingual collection The Talk of the Town and to specially thank Peter Fallon for all the care he took with the translations of my poems from the original Irish. He has shown great commitment to the publication of contemporary Irish-language poetry translated into English, which has made all the difference for poets like Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill.

EXTRACT:

Scaradh na gCompánach

Labhrann Caitríona, Cuntaois Thír Eoghain:

Ar bhruach na Feabhaile, tuar

a tháinig chugam i dtaibhreamh:

glaoim chugaibh, a fheara, d’impí-

an imeacht seo, ní tairbheach.

Mar a scaiptear deatach,

Is amhlaidh a scaipfear muidne

Mar chéir i láthair na tine,

Is amhlaidh a leáfar.

Insint ag caoineadh gaoithe

Ar a bhfuil i ndán dúinn,

Sa leabhar ag an fhiach dubh,

É sin, nó i dTúr Londan.

Mo mhac óg, mo mhuirnín Conn,

Mo leanbh féin, mo laoch,

Gan é ach cúig de bhlianta faram,

Is gach aon snáth le réabadh.

Fonn a bhí orm, an chéad lá riamh

Éirí den turas go Rath Maoláin:

Ach chuir m’Iarla orm gabháil ar aghaidh

Is ár mac a fhágáil faoi lámh an Ghaill.

The Parting of the Ways

(As spoken by Catherine O’Neill (née Magennis), Countess of Tyrone)

On the Foyle’s riverbank a foreboding

came on me, and I fitfully sleeping.

Men, I pray and plead with you,

what’s the good in this going?

Just as smoke can be scattered,

so we’ll be dispersed.

Like wax by hearthside

we’ll come in to our worst.

A keen wind will report

what’s in store as it rages,

in London’s Tower,

or through the raven’s pages.

My youngest son, my darling Conn,

child and hero heaven-sent,

with me a mere span of five years:

now each and every tie’s to be rent.

To abandon the trip to Rathmullan

was from the start my most ardent wish

but he, my own Earl, forced me to proceed

and abandon our son to the grip of English.

Translation by Peter Fallon

Caitríona Ní Chléirchín