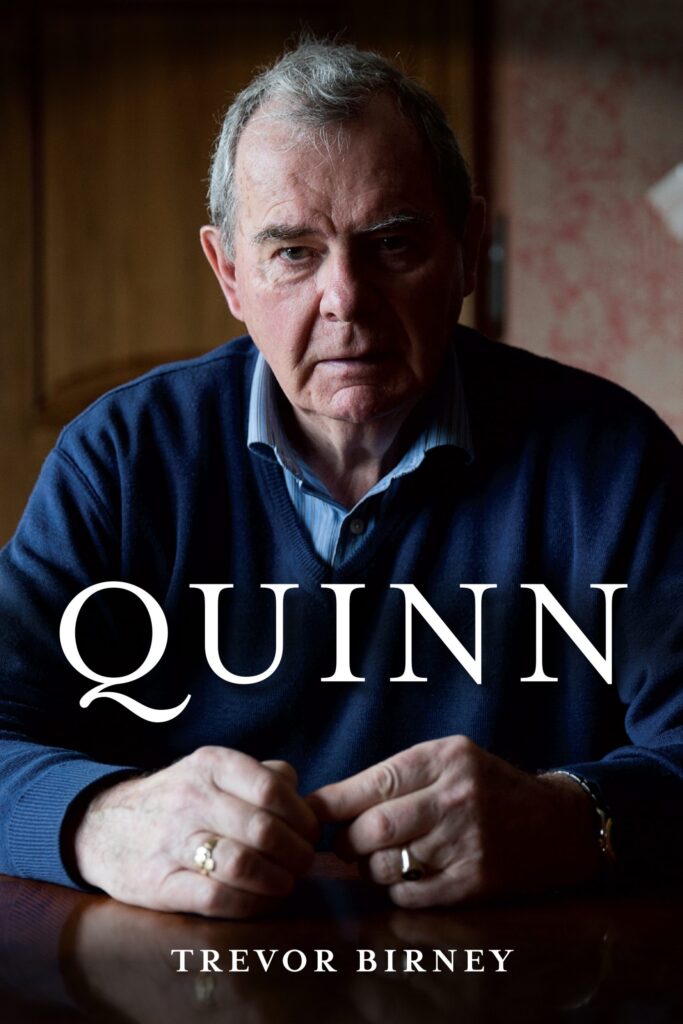

Quinn|Trevor Birney|Merrion Press|ISBN 9781785373992|€19.99

The vaulting ambition of Seán Quinn—an Irish tragedy, Greek style

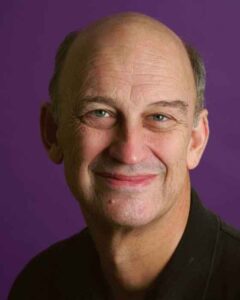

by John Kirkaldy

Apart from possibly Rip Van O’Winkle, there must be virtually nobody in Ireland who is not aware of the life and times of the bankrupt billionaire, Seán Quinn.

Trevor Birney has written a real page turner of a story that has every ingredient of a Greek tragedy. Quinn came from a very ordinary background and had become a millionaire by the time he was thirty, employing many thousands. Virtually every time the reader turns a page, Quinn has made another acquisition. In 2008, he gambled his fortune on Anglo-Irish Bank shares and lost spectacularly.

The story has every ingredient of a great epic (indeed Birney was the producer and director of a recent three-part TV documentary on Quinn’s life). Compelling detail follows compelling detail: the boy who failed his 11+ for grammar school, a seemingly unstoppable rise, a finger in virtually every pie, the richest Irishman and the 164th in the world, meltdown, endless confrontations, scandals, allegations of corruption, court cases, fallouts, public protests and attacks on former employees and Quinn business premises.

Hubris

It all started in 1968 on a newly inherited, small farm at Derrylin, County Fermanagh, just inside the Northern Irish boarder. Quinn discovered gravel in his fields, an integral part of making concrete and road construction.

In 2008, his personal wealth was estimated at €4.722 billion (£3.73 billion).

Birney comments on Quinn’s business methods: ‘He wasn’t in business to compete, he was going to win. And he wanted his staff, and the local community, to know that what he was doing was bigger and better than anyone else in the country, if not the continent.’

The Greeks had a word for it – hubris. As his empire grew, it seemed that everything Quinn touched was successful. The formula of grabbing opportunities, working hard, and often borrowing the money—always seemed to work. An early visitor to Quinn’s office noted, ‘he didn’t act like the boss. And he certainly did not look like a millionaire.’

Mounting problems

But by 2004, a colleague had noted a definite change, ‘the problem with Seán was that he began to believe his own myth. He liked to be the man who plays cards for 50p but, in reality, he liked to be in those high-flying circles.’

With the wealth, came the trappings – large car, palatial home and private jet.

Diversification also presented mounting problems. Early ventures, such as cement, glass, radiators, pubs and hotels (the Slieve Russell Hotel in Ballyconnell, County Cavan was a centrepiece), were relatively straight forward.

The first setback came in 2000-2002 in the dotcom business. He escaped, thanks to some fancy footwork, but, ominously, Quinn admitted that he hadn’t done his homework in a market that he did not really understand. ‘We paid heavily,’ he admitted.

Nemesis

Nemesis came with Quinn’s growing involvement in insurance. In January 2007, Quinn Financial Services, founded in 1996, purchased BUPA Ireland. In the same month, he increased his shareholding in Anglo-Irish Bank to 5% through a deal with the Swiss-based, Credit Suisse; this later increased to 28%. (At this time, the Quinn Group employed 5,500 staff throughout Ireland.)

The Bank, along with all other Irish financial institutions, saw its share price completely collapse in the later part of 2008. Shares were trading at as little 20c, from a high of €10.15, and in January 2009, the Irish Government took full control of the Bank. Quinn faced ruin.

It became increasingly obvious that the Quinn Group had borrowed massively from its insurance branch to cover falling stock market investments and to finance share-buying in Anglo-Irish Bank.

It is a riveting story and Birney tells it very well. A lot of research is lightly worn, as he guides the reader – using simple and jargon free English – through an increasingly complex world.

The book benefits from a lot of interviews, some on the record and others not. Quinn himself cooperated in the making of the documentary but distanced himself from it, when he found that it was not going to be used as his apologia.

Continuing drama

As with all good epics, the drama continued. In November 2011, Quinn was declared bankrupt in Northern Ireland; this was annulled on appeal, but he was declared bankrupt in the Republic of Ireland in January 2012.

In November 2012, he was sentenced to nine weeks in prison for contempt of court. The courts and the Irish Bank Resolution Corporation tried to investigate the convoluted world of assets, involving Britain, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Ukraine, Russia, Sweden, Switzerland and a lot else. This was made even more complicated by ownership shared between Quinn, his wife, Patricia, their five children and other family members.

There was considerable public sympathy for Quinn. Tony Doonan, a border native and business man, spoke for many, ‘it wouldn’t have happened to a Dublin company. Quinn is being singled out because he’d the audacity to take on the establishment.’

His companies provided a lot of employment (much was made of his record of not laying off employees). Quinn also had strong links and was a sponsor of the GAA.

There were public demonstrations and marches. A clandestine group, calling itself the Molly Maguires, began to attack former Quinn businesses, causing €10 million of damage.

In December 2014, there was a second coming, as Quinn returned as a consultant, in the hope of sorting out the tangled mess. Rifts soon, however, began to develop between his former executives and resulted in a final withdrawal. Attacks, which had abated, resumed and culminated in a brutal assault on Kevin Lumley, Quinn’s former right-hand man (Birney’s book claims that there was an MI5 connection in this).

Quinn remains something of a folk hero in the border area. ‘Seán Quinn was never in my home but I wouldn’t have a home if it wasn’t for Seán Quinn,’ a sign read during the demonstrations. In Greek tragedy, a great man is ruined by a fatal flaw. Did Quinn share Macbeth’s ‘vaulting ambition’?

John Kirkaldy has a PhD in Irish History, worked for many years with the Open University and has been reviewing for Books Ireland since 1980.

He has contributed to three Irish history anthologies, a school textbook, and has been involved in a number of Open University History documentary series. Aged 70, four years ago, he went round the world on a much delayed gap year described in his book, I’ve Got a Metal Knee: a 70-Year Old’s Gap Year.