by Lindsay Myers

Storytelling is fundamentally about communication and connection. As the character of C. S. Lewis in William Nicholson’s play, Shadowlands, so aptly put it: “we read to know we are not alone”. When we tell stories to children we create links between our childhood and theirs, and it is not by chance that many of the most well-loved children’s books started out as bedtime stories for a specific child.

The role that children have played, and continue to play, in the genesis and evolution of children’s literature has not been particularly visible within the children’s-book trade. It is not that there is any malice involved, rather that regardless of our intentions we have effectively created a two-tiered system: on the top there are books written and illustrated by adults— published by mainstream publishers, reviewed by professionals, and marketed towards children, and on the bottom there are books written and illustrated by children – work which is often self-published, rarely reviewed, and limited in circulation.

If we stop to think about it, both of these types of book are effectively the product of adult/child collaborations, for neither could exist without the other. Might our understanding of children’s literature change if we were to adopt a more holistic perspective of the story-making process? If we were not just to acknowledge but embrace the involvement of children in the process?

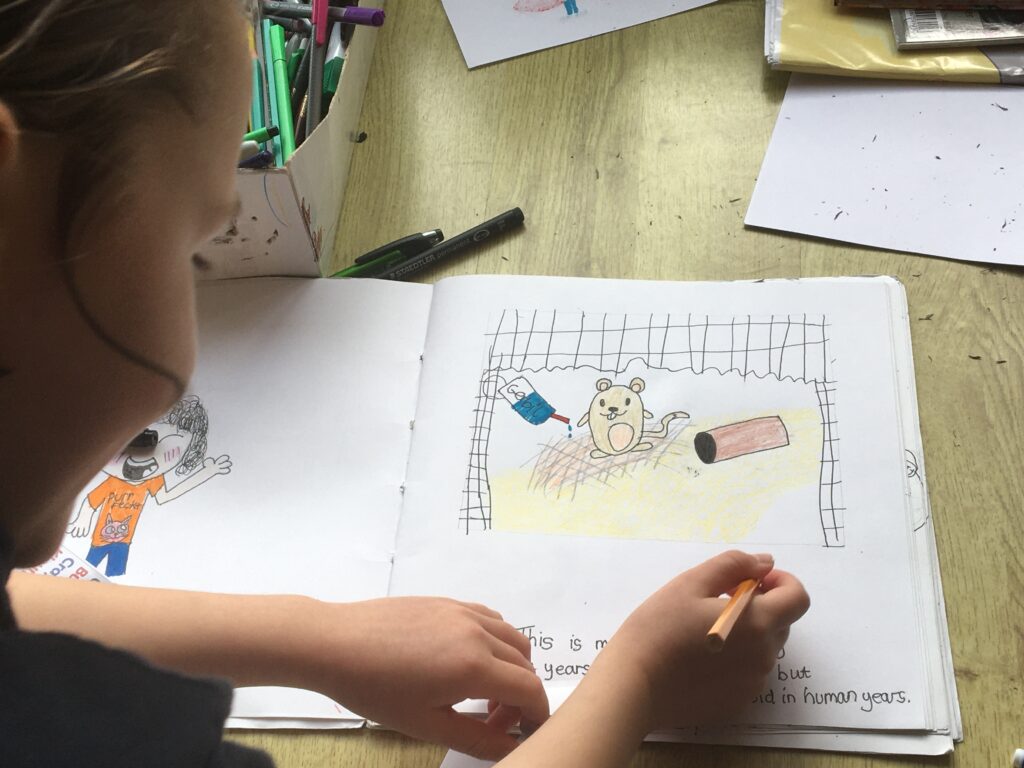

When I began making a children’s picture-book with my eight-year old daughter Tara, I didn’t know what to expect. I knew that my daughter was an excellent artist for her age and that the opportunity to illustrate a book would help her grow in self-confidence but I had absolutely no idea how we were going to pull off this joint adventure.

I wanted our book to be about something that happened to me when I was the age that my daughter is now. I chose the time that my pet gerbil bit me—the day I realised that the only way to get out of an impasse is to see things from another’s perspective. I was fairly sure that my daughter would enjoy hearing the story, and when I saw the drawings she was creating I knew that she had understood on a very deep level both the essence and the significance of my experience.

In her hands, however, the gerbil was not so much a pet as an equal, and the more she developed his character the more I realised that my childhood memory was transforming in her hands: it was expanding, becoming more imaginative and entertaining.

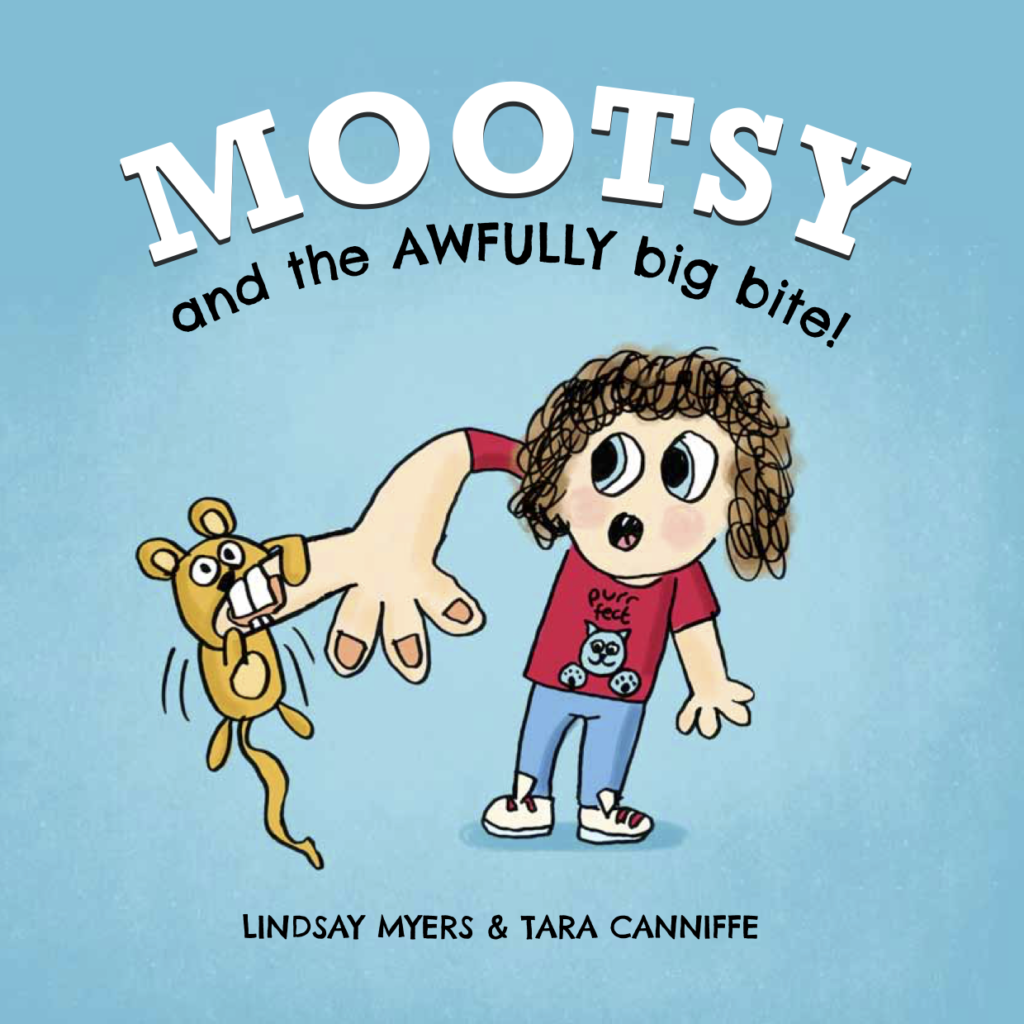

When we finished the book we couldn’t stop reading it. I knew then that we had to find a way to publish it, if for no other reason than to show the world that children have as much to teach us about the process of story-making as we have to teach them—that as adults we cannot afford to take exclusive ownership of children’s literature, or to think that it can exist independently from the children for whom it is created.

If J. K. Rowling’s recent novel, The Ickabog, has shown us anything, it is that children’s illustrations can be as diverse and as fascinating in their interpretation of a story as those of adults. Why is it, then, that children’s art, no matter how much we admire it, tends to be viewed as inherently less sophisticated than an adult’s, given that the most successful children’s-book illustrators actively pursue a childlike style? Are children’s illustrations really less mature? My daughter’s art is developing for sure, but what artist’s isn’t?

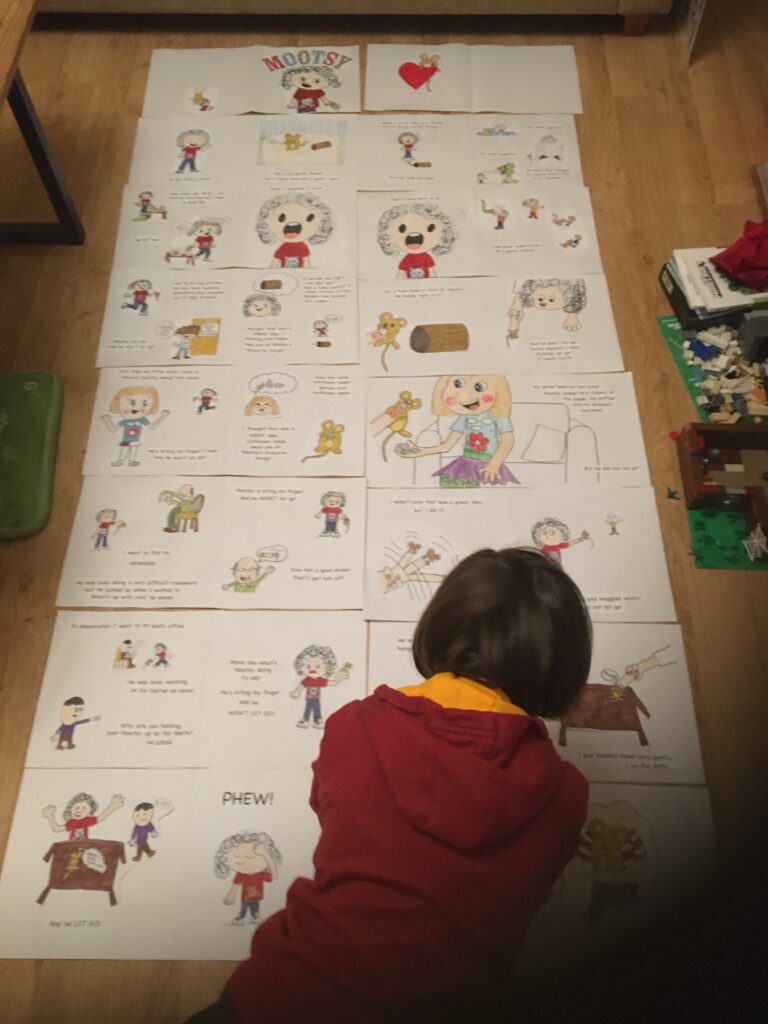

There can be little doubt that the process of illustrating our picture-book enabled my daughter to develop the consistent style necessary to illustrate an entire book. One of the ways we made sure that the work had internal coherence was by scanning her black and white drawings into photoshop and colouring them digitally in the colours that she had originally used. Having the drawings in this format enabled us to add coloured backgrounds and to develop a unifying colour palette, which, in turn, made the whole book look more professional.

At no part in the whole process did my daughter feel that that I had appropriated her art or taken away her artistic control. Quite the contrary, she was inspired by the journey. And that is when it hit me—that the divisions we make between the work of children and the work of adults, in addition to being somewhat arbitrary, can easily limit the potential of intergenerational collaborations. They can make us feel like we cannot touch the work of children and that they, in turn, need to be kept away from ours.

Children are not as aware of the politics of publishing as adults are. To them a good book is a good book, so when we shared the story of Mootsy and the AWFULLY big bite! with Tara’s class we were delighted to see that many of her peers immediately began drawing new adventures for Aoife and her gerbil. They were empowered by the story and by Tara’s role in its creation—just as we were empowered making it together.

Mootsy and the AWFULLY big bite! is available to buy on our website www.mootsyandme.com. All of the proceeds are going to Galway SPCA because together we can make a BIG difference!