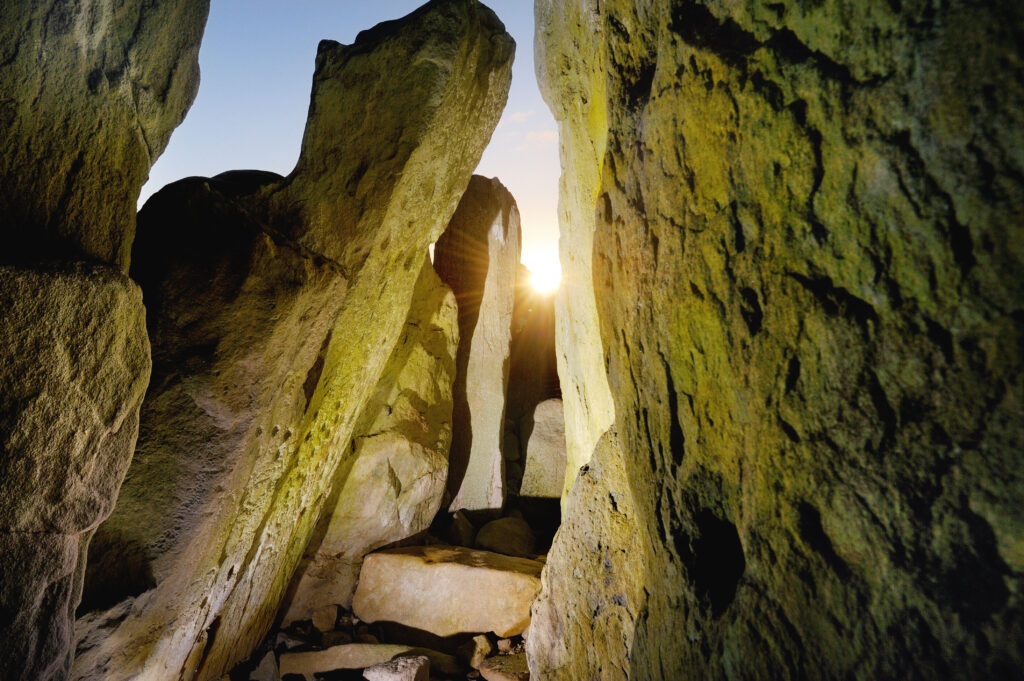

“There is a great sense of pilgrimage in that journey up into the darkness.”

In time for winter solstice Clare Tuffy shares her unique experience of ushering people to the light at the Boyne Valley tombs.

This year, things are different—but you can watch a livestream from Brú na Bóinne here

Waiting for the Light

I have worked for the Office of Public Works in the Boyne Valley since the early 1980s. I have been privileged to be at Loughcrew, Newgrange and Dowth for equinox dawns, winter solstice sunrises and winter solstice sunsets on hundreds of occasions.

I sometimes think that no one who has ever lived since the monuments were built has witnessed as many sunrises or sunsets at ancient monuments as I have, but I also know that no one has waited in darkness in Neolithic chambers on cloudy, wet, dark days as many times as I have! So, what’s it like to be there?

Clare Tuffy was a speaker at the Pathways to the Cosmos conference, and is Visitor Services Manager at Brú na Bóinne

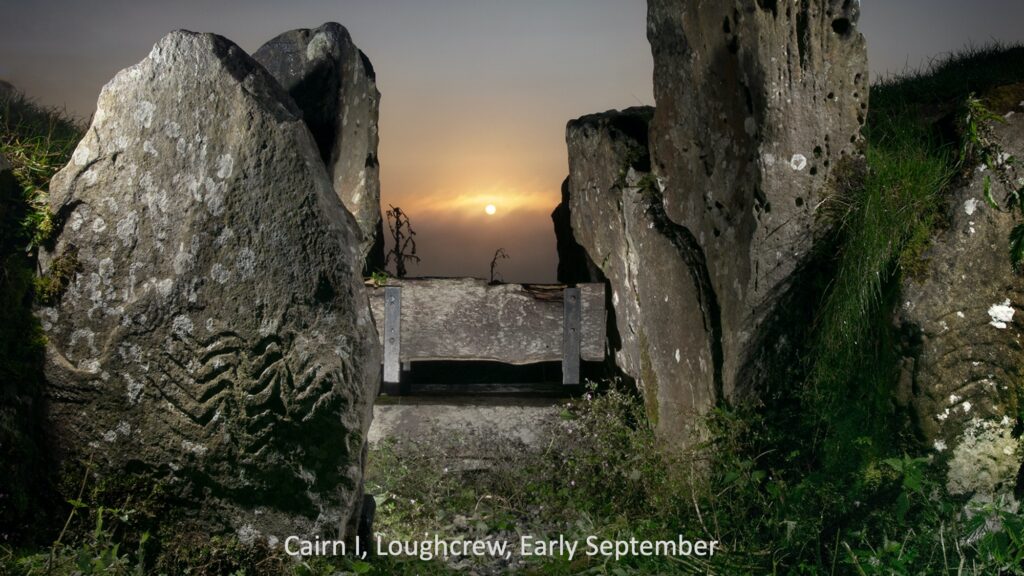

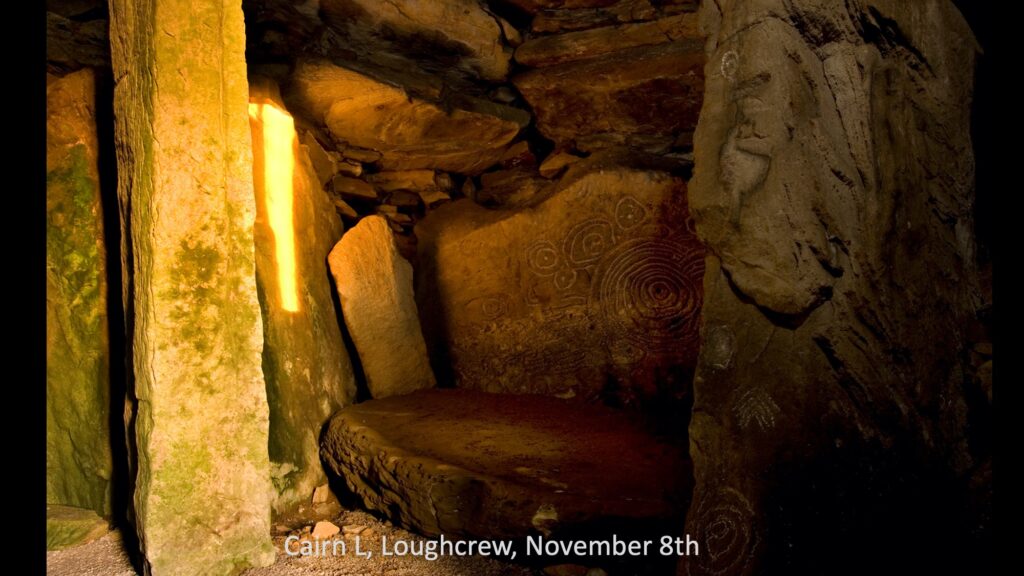

Loughcrew

First of all, a proviso: my experience is bound to be different from that of a visitor, as my OPW colleagues and I are there to facilitate others’ enjoyment of the events and to protect the monuments.

Each monument is distinct, of course, and each sunrise or sunset is different, but what is certain is that it is the location in the landscape of the sites that makes the real difference to the light experience.

The OPW has been facilitating access to Cairn T at equinox dawns in March and September for almost 30 years. In March sunrise is just after 6.00am and in September it is just after 7.00am. The difference, of course, is that the clocks have not yet gone forward for summer time around 21 March.

We always go for the actual day of equinox and a day on either side of that. In March it can be very cold, and getting out of bed at 4.15am is a challenge.

Pilgrimage in the dark

We OPW staff meet in the car park, and then Leontia (my dear friend and long-time colleague) and I set out to climb the hill with one of our Depot colleagues; in recent years this has been Frank Taaffe, before him it was Peter Boyle, and for many years before that it was always Ben Devine.

Climbing the hill is difficult—a steep climb in darkness. We stop often to admire the lights of Oldcastle … or is it so that I can catch my breath? As we climb, people overtake us with the determined hurried air of passengers just about to miss a flight.

There is a great sense of pilgrimage in that journey up in the darkness.

A special place

As we wait for dawn, we chat and greet old friends and welcome newcomers. Cheery calls of ‘Happy Equinox’ ring out! There is a great sense of excited anticipation if the skies look promising, and a more subdued mumble of talk if it looks like it is going to be cloudy.

What brings people? In 2008 we had the earliest Easter in nearly 100 years and the day of equinox fell on 21 March, which was also Good Friday.

This seemed to us to be a strange confluence of Christianity and the older religion.

The sun broke through long after dawn, but while we were waiting I asked some of the visitors why they were there. We met two Afghani lads who were celebrating their New Year; we met two Hindu women who were there to celebrate Holi, the Festival of Colour; we had a 40th birthday celebration, a 60th birthday celebration and a marriage proposal—and it still wasn’t 6.30am!

Below us the fog rolls in peaks like a gigantic ocean; it is as if we are on a hilltop island way above the world. All eyes are fixed on the eastern horizon, and almost inevitably as the sun is just about to rise someone will beat a drum.

I can say with hand on heart that there is no more special place to be than on top of Loughcrew Carnbane East waiting for dawn when skies are clear.

The chat falters and we wait, almost afraid to breathe. When the sun rises we relax, and the ever-present Loughcrew larks start to sing. We get down to the business of organising the long queues of people who make their way inside the cairn. The sunlight is generous at Loughcrew and stays in the chamber for almost an hour. As we stand outside there is a constant mumble of talk.

We let people in and out of the chamber. We mind the dogs as their owners venture inside. We wait until everyone has left the hill and then we descend. Sometimes we get so cold that we dare not try to go back down until our feet have thawed out, so we circle the mound to bring feeling back into our toes.

Newgrange

As I suspect has always been the case, Newgrange for winter solstice dawn is a very different experience.

Nowadays there is a lottery for places inside the chamber at sunrise. Last year we had almost 33,000 applications from all over the world.

We hold the draw on the last Friday in September, and it is the schoolchildren who live near the monument who choose the lucky winners.

On the day we contact people to tell them that they have won, we think we have the best job in the world.

What always strikes us is how many lottery winners tell us that they had a strong feeling that they were going to win and/or that their visit to Newgrange was one of the most special days of their year.

Arriving light

We are open to the public for six mornings, with ten lottery winners inside on each of those days. Each lottery winner can bring a guest—we think it is only right that on such a special occasion you have someone to hold hands with in the darkness.

What many people don’t realise before they have waited for dawn is that it is bright for quite a while before the sun clears the horizon, so our lottery winners often feel that we have missed the event long before it starts.

On 21 December there can be several hundred people outside the monument, and the noise they make drifts inside into the dark chamber.

The people waiting inside lose a sense of time very quickly as their eyes adjust to the darkness. Some people are more comfortable than others in darkness. It takes a little while for visitors to settle and be calm.

On a clear morning we almost bore a hole in the floor of the chamber with our eyes, watching for that first narrow beam of light to strike. No matter how often we tell those waiting that the light will hit the floor, they look longingly out towards the entrance. I sometimes think it is as if they are looking into the projector rather than at the screen. The first beam hits the floor and it is, as Prof. O’Kelly described it so many years ago, a pencil of light . . . a pencil-sized narrow beam of light.

As we watch, the beam widens and swings across the floor. At its peak, it is as if the light is beaming from above, and there is a dark space that separates the light in the chamber from the light shining in the passage.

The people standing in the chamber on either side of the sunbeam look like they are gathered around a fire. The light stays in the chamber for seventeen minutes. It doesn’t sound like a long period of time, but after the initial excitement of the sunlight’s arrival the light show works its magic and time seems to stand still.

Reactions

People react to the occasion in different ways; we have had tears, singing, valued items being left in the sunlight to be blessed and marriage proposals! Everyone feels the urge to get down on their knees and feel the sunlight on their faces as if it were going to feel warm, and we encourage people to do this. As I watch them, I think that the builders of the monuments would be pleased.

On a cloudy day, as I said, the atmosphere is different. We always go inside and wait, even though we know in our hearts that there will be no sunlight. As people relax and feel comfortable in the space, the chat starts. There is an intimacy to the conversations that I can only describe as the kind of whispered chat that my sisters and I had in bed long ago after our mother shouted to us to turn out the lights.

The people who have been waiting on the outside of Newgrange on those dark mornings often ask us what kept us inside for so long. And it’s hard to explain, except to say that we can go deep and become quite philosophical.

We talk about the meaning of life and the meaning of death. We discuss the motivation behind these great monuments and the urge to make a mark.

We talk about the builders of the monuments: the differences and the similarities between us and those who waited so long ago. We talk about our lives and our losses, and when we finally turn on the lights and are blinking in their brightness, we are amazed to find that the chamber, which seemed to grow as we spoke in darkness, is actually quite small.

Dowth

I always say that going to Dowth South for winter solstice sunset is like being in a pub on St Stephen’s Day! Everyone is in good form, the occasion is relaxed, and there is a great sense of relief and almost a giddiness that all of the formalities of the morning at Newgrange are over.

Dowth South is spacious inside and so we can accommodate far more people than at Newgrange. There is no lottery and all are welcome.

Leontia, Frank Taaffe and I are greeted like celebrities when we arrive at about 2.30pm with the key! When we open up, I go inside the chamber and Leontia and Frank stay outside to organise the visitors.

As people come inside, I recognise most of them and call out to them, offering my hand to steady them. Once they are reassured that I am a friend, I must physically take them and park them until their eyes adjust to the darkness.

We greet one another as if we haven’t seen each other for ages even though we may have spoken at Newgrange in the morning. We move to stand back out of the path of the light.

At Dowth, though, the light seems almost secondary to the sense of gathering and the excitement of being there. It seems that those of us who go to Dowth regularly spend most of the time inside asking people to get out of the way of the light. In their excited and distracted state, they stand still and lift their legs up as if the light were somehow a liquid—a puddle that they can step out of.

A couple of years ago Ken Williams was with me in the chamber, as were many more. Ken, as always, was trying to get photographs of the light, but a guy came in with a harp and just sat in the middle of the chamber floor.

Everyone in the chamber asked the harpist to move, but he was so stoned or otherwise overwhelmed that he didn’t understand what we were asking him to do. He didn’t budge. Frank Prendergast was outside the monument giving an impromptu talk on archaeo-astronomy while Prof. Gabriel Cooney came inside to see whether he could help with any questions of an archaeological nature.

After speaking to several people he knew, Gabriel rejoined Frank and the group outside. Some minutes later, I heard a woman I knew speaking about a theory of hers about life in the Neolithic. She finished her soliloquy with the question: ‘What do you think, Gabriel?’ I said, ‘Deirdre, Gabriel is not here.’

I think that even Ken, who always gets the picture, may have failed that day—but you know, it didn’t matter, as we had been there, we had spoken and laughed and gathered as a tribe and enjoyed the merry confusion.

As the sun sets, people climb to the very top of Dowth to stand in the last rays of the evening light and watch the sun set behind Newgrange. We lock up and go home and always, always remark that the shortest day of the year is one of the longest for us.