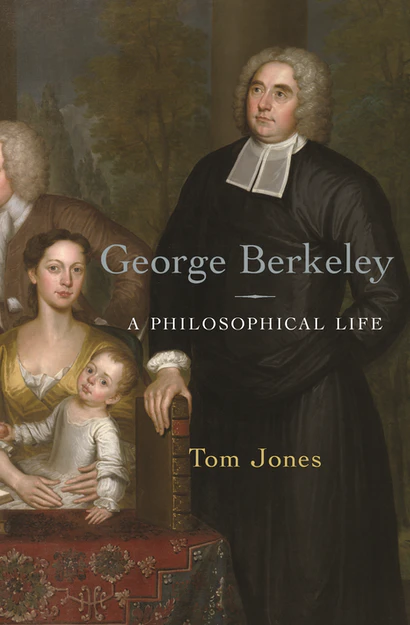

George Berkeley: A Philosophical Life|Tom Jones|Princeton University Press|ISBN: 9780691159805|£28.00

“Who was George Berkeley? Philosopher, mystic, educator, missionary, progressive, bigot, slave owner? In this new biography, Tom Jones rejects easy answers and insists that we must see Berkeley as all of the above.”

—Kenneth L. Pearce on a new book about Ireland’s most renowned philosopher.

If you’ve heard of George Berkeley (1685–1753), chances are you know him for the philosophical works he wrote as a young lecturer in Trinity College.

These two short books have earned Berkeley a place in the canon of Western philosophy, an honor accorded to no other Irish writer. But they’ve also earned him a reputation for bizarre religious mysticism—“God-appointed Berkeley that proved the world a dream,” as Yeats famously wrote. In these works, Berkeley denies the existence of matter and paradoxically claims that this denial is needed to save common sense from the wild ideas of atheists, skeptics, and free-thinkers.

Educator and missionary

In his lifetime, another picture of Berkeley was prevalent. Berkeley was known as an educator and missionary. This reputation was earned by the years Berkeley devoted to his Bermuda Project, a utopian scheme to found a college on a remote island to educate colonial and Native American students who would spread virtue and Christianity across North America.

The scheme ultimately failed but left enough of a mark on American higher education that George Berkeley’s name is now attached to both Berkeley College, Yale and the University of California Berkeley.

Progressive ideas

Or perhaps you’ve encountered yet another picture of Berkeley, based on the late (1735) work The Querist, which has been known to appear in Irish politics from time to time. This strange work is, as the title suggests, composed entirely of questions, and is aimed at finding a cure for Ireland’s economic ills. Here, Berkeley (by this time Anglican Bishop of Cloyne) pushes a variety of progressive ideas: an Irish national bank to issue fiat currency; the repeal of the Penal Laws; conducting Anglican services in the Irish language; the admission of Catholics to Trinity College; the founding of a Catholic university in Ireland, and various schemes to punish absentee landlords and ensure that Irish peasants have “shoes to their feet, clothes to their backs, and beef in their bellies.”

However, these progressive ideas sit uncomfortably alongside complaints about the congenital laziness of “our native Irish” and the suggestion that this laziness might be cured by a combination of eugenics and forced labor (including for young children).

Horrific history

Recently still another picture of Berkeley has come to the fore, a picture that connects closely with the most disturbing portions of The Querist. In the 1720s, when Berkeley travelled to Rhode Island in pursuit of his Bermuda Project, he purchased three or four African people—Philip, Edward, Anthony, and Agnes—and held them as slaves to work a farm that would provide food for his college.

(Surviving lists do not match, and it is possible that Edward and Anthony may have been the same person.) Further, in the proposal for his college, Berkeley suggests that Native students might be supplied by kidnapping—a suggestion that has particular resonance today, as Canada, the United States, and Australia all grapple with the horrific history of boarding schools for indigenous students. At the same time, however, Berkeley insisted, against many of his fellow colonizers and slave owners, that Africans and Native Americans were full human beings with souls who could be admitted to baptism.

Messy complexity

So who was George Berkeley? Philosopher, mystic, educator, missionary, progressive, bigot, slave owner? In this new biography, Tom Jones rejects easy answers and insists that we must see Berkeley as all of the above.

Jones rejects a previous tradition of hagiography but also avoids the opposite extreme of demonization.

Rather than trying to determine whether Berkeley was a hero or a villain, Jones acquaints his readers with the full, messy complexity of Berkeley’s life in its historical context.

Weighing in at 541 pages (plus extensive bibliography and index), this is the most detailed and comprehensive biography of Berkeley to date, and well equipped to handle the complexity of Berkeley’s many faces. Professional scholars will be impressed by the thorough research and documentation. The lay reader will also be able to appreciate this complex portrait of Berkeley as a man in his time, a multi-faceted individual who, over the course of this book, comes to be very well known and yet somehow remains elusive.

New ground

In a number of areas, Jones breaks completely new ground, unexplored in previous scholarship on Berkeley. Chapter 7, “Others,” is particularly timely, examining and comparing Berkeley’s attitudes toward the Irish peasantry, enslaved Africans, and Native Americans.

Chapter 10 does an outstanding job of contextualizing Berkeley’s Bermuda Project, and showing the ways in which Berkeley’s attitudes were and were not typical of his time. The Bermuda Project is shown to be a manifestation of the broader phenomenon of 18th century missionary Anglicanism.

To mention just one more place where Jones’s work is particularly novel, in chapter 16 he follows the history of Berkeley’s family beyond the bishop’s death. Jones is the first to trace out in detail the sad fate of Berkeley’s children: of the three who survived to adulthood, two were permanently institutionalized for mental illness.

A contested legacy

Today, Berkeley’s legacy is contested. There are diverse opinions on the meaning or significance of attaching Berkeley’s name to buildings and institutions—including a library in his alma mater, Trinity College Dublin.

Historical inquiry alone cannot settle the question of what Berkeley symbolizes (or should symbolize) for us today.

But any conversation on this difficult topic should start from a good grasp of the real historical Berkeley. On this topic, Jones’s book will be the definitive resource for decades to come. Further, for scholars of Berkeley’s philosophy, Jones’s book draws surprising and illuminating connections between different aspects of Berkeley’s thinking and various events in his life.

Finally, for the lay reader, the book provides a detailed portrait of Ireland’s most renowned philosopher, in all his complexity, shaped by his time and place, in some ways radical and in others deeply conservative, neither a hero nor a villain, but a human being who lived a philosophical life in 18th century Ireland.