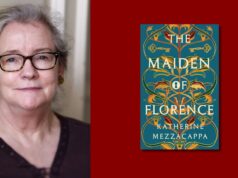

from Empty House|edited by Alice Kinsella and Nessa O’Mahony|Doire Press 2021|978-1-907682-80-3|€15.00

by Rick O’Shea

Alan weighed himself as usual, shaved while the coffee was brewing, and brushed his teeth thoroughly just before leaving for work. You shouldn’t let your standards slip just because you’d be a puff of vapour tomorrow, he thought.

The circumstances of the impending apocalypse were so well known and long discussed at this stage it was a bit like saying the word orange repeatedly—they had lost all meaning. Today, at around 11.34pm GMT, an asteroid would hit the Earth and kill almost everyone.

Orange. Orange. Orange.

The irony of Earth being annihilated in a fashion already played out in many histrionic Hollywood films wasn’t lost on most. It had been detected months ago and every possible option had been argued over and eventually discarded by the world’s finest minds, murkiest politicians and even a few consultant B Movie experts. In the end every potential Bruce Willis all shrugged their shoulders, manfully. Finally, a month before it was due to happen, the world had been told that it was fucked. Something many people had suspected for a long time had scientific confirmation.

It was, as no shortage of level-headed scientists had told every rolling news channel, an ‘extinction level event’. An E.L.E. In no time at all Twitter had christened her ‘#Ellie’, like she was the new cat at 10 Downing Street. The hashtag had been the top trend on Twitter for weeks right up until the last few days when social media had gone remarkably quiet. Alan had always fancied the idea of social media quieting down a bit, it was just a shame it took the extinction of the human race for it to happen.

Tomorrow the entire headcount of Homo Sapiens would amount to a few thousand people bunkered down in military installations and roughly fifty off planet. After hundreds of millennia of evolution, we had finally gotten a foothold on another celestial body only to find the stool kicked out from under us by random, blind chance. Forty of those were on the moon base the Chinese had completed a few years back. The bottom half of the internet was sure they must have had an advance warning, they must have known something for years now. It was depressingly unsurprising to see that racism was going to do its absolute best to survive the destruction of humanity the way cockroaches most surely would too.

The others were some randomly lucky (or unlucky) astronauts, cosmonauts and three tech billionaires who had made it into orbit before the big smash. The only other attempted last-minute escapee was the eternal despot of one of the world’s most secretive regimes. He had been successfully shot into orbit with his country’s fledgling space program’s dying breath. At least that’s what his people were being told. In reality his poorly prepped rocket had broken up somewhere over the Sea of Japan. State TV was showing a graphic of the dear departed leader’s position in orbit, serenely circling the planet. Newsreaders would report on his survival right up until the last moment. That was dedication to your job, Alan thought.

Alan had that too. Every day since the revelation of E Day (there was always a catchy name for things—it maintained some sense of normality) he’d opened his shop of second-hand curios as usual. He was an only child; his parents were dead and for the last four years the shop was the closest thing he had to love in his life. Realistically, what else did he have to do today but open the shop? It was a question he asked himself every day of his life.

The shop had been at the edge of the previous great disaster to hit the area, a tsunami of gentrification whose waves had lapped the shores of his front door. It crouched in disappointment between a wheatgrass juice emporium and a crystal healing therapy centre frequented by minor celebrities. Neither of his neighbours were open, as wheatgrass, crystals (and even minor celebrities) had unsurprisingly gone out of fashion in the last few weeks.

Luckily, he hadn’t been looted as many others had. People seemed to have similarly lost the need for rotary dial telephones, vintage walking sticks and phrenology busts. Alan thought people just lacked imagination. They’d all be particularly useful to beat a looter to death with if the opportunity had arisen in recent days. It hadn’t. Still, the morning was young.

For the first time in a week, the door opened. It was so unexpected, the sound of the tiny bell above it ringing was almost celestial. A woman slid herself between the door and the jamb as if she were a piece of paper brought in by a breeze.

‘You don’t think they’re monitoring us, do you?’

Christ.

‘I’m not exactly sure what you mean and, even if there was a ‘them’,’ Alan said, ‘I’m fairly sure ‘they’ have other things on ‘their’ hands today, don’t you think?’

She unclenched her shoulders, but only slightly.

‘Well no, not really, they have always been sticklers for detail.’

She had a bizarre accent that was vaguely clinical, as if she’d learned it from a 1980s travel cassette. After hovering around a table of vintage Toby jugs and toying with them in an unconvincing fashion for a few minutes, she came up to his till.

‘I will be from… the future,’ she whispered conspiratorially.

Leaving aside the awkward but possibly technically-accurate tense usage, this wasn’t surprising to him. In the time he’d been running the shop, he’d had what he considered to be more than his fair share of nutjobs, whackos and general messers cross his threshold looking for rifts in the space/time continuum or Jesus or whatever.

He decided to play along. After all, what else did he have to do?

‘The future. Fair enough…’

She looked around hesitantly, saying, ‘I’m sorry, but you can’t be too careful.’

‘No, I suppose you can’t. Be careful of what?’ He regretted the words the moment they were out of his mouth.

‘The monitors. Keeping an eye on all of… Well, you must be aware.’

There were many things he was aware of that morning; everything from the chance of showers to a palpable sense of his own mortality given the day that was in it. He thought a noncommittal answer might be the way to go.

‘Quite.’

She had the strangest eyes. When she looked at him, he felt pinned, like he’d just been accused of a crime he didn’t know he had actually committed. He wasn’t sure how this was making him feel, but unlike unbidden conversations with most strangers, he didn’t actively dislike it.

Her clothes were odd—none of the future ‘tinfoil and plastic’ nonsense that 1950s sci-fi had told him to expect. Instead, she was dressed a little like Miss Marple. All tweed and blocky heels. Despite being decades too young for it, she even wore vintage eyeglasses on a chain.

‘What’s with the get up?’

‘Get up? I am up. I could sit down if you would prefer?’ she said, slightly confused.

He realised he was going to have to be a bit more literal to play the time traveller roleplay game.

‘No, I mean your clothes. They’re a little… old fashioned.’

‘Are they? We have some small problems with that. Only fragments of this time survive so we improvise. I am mostly correct?’

‘Close enough.’

She seemed to regain her composure.

‘I’m here to conduct a survey of the last members of phase one of our species. To gather information that might be useful to us.’

‘That’s lovely. Interesting work, is it?’

Her look changed from authority to slight confusion again.

‘I may not be speaking clearly. I said I am from the future. Here to talk to you about the last day of Earth.’

‘And who exactly are you?’ said Alan, at least part of his brain wondering why he was engaging with this cuckoo. It was probably from not having properly spoken to anyone for the last ten days.

‘My name is Ellie.’

He uncharacteristically snorted.

‘You have got to be fucking kidding me. Why on Earth would parents in the future name their kid that? You’re seriously telling me that they named you after a vast, horrific, inexplicable catastrophe? It’s like calling you ‘Electronic Dance Music’.’

A smile played at the edges of her mouth.

‘Ellie, I’m Alan, and normally I’d be far too busy to deal with questionnaires like this.’

He gestured at the vast, dusty poorly lit stacks of shelving imperiously.

‘But as you can see, normal has pretty much gone out the window around here, so fire away.’

She flinched; he reconsidered his phrase.

‘Sorry. You’re from when in the future exactly?’

‘I’m not sure how many years in your future to be honest. Things get fuzzy for a few millennia while we drag ourselves up out of the dirt and learn how to make decent sandwiches again but everything is pretty civilised from my time.’

He started thinking about what he might like for lunch.

‘Right, could you be any more specific?’

‘I’m from the year 5,641. We started counting again at one stage when everything settled down. It’s all a bit arbitrary really but then again, so was the year zero in your calendar.’

‘Oh, right. And did you lot have to go through the whole ‘building the pyramids’ and having a messiah turn up again?’

‘There’s no need to be facetious, Alan.’

Right.

‘Right. I’m fairly sure if you are from the future you shouldn’t be telling me any of this though. Isn’t that one of those rules of time travel things?’

Her tone shifted.

‘You’re all about to be vapourised by a giant rock. How exactly could I floop this situation up any more? It’s not as if anything I can tell you is going to change any of this now, is it?’

She had a point.

‘Surely knowing the human race will survive in some form is some small comfort?’

He hadn’t the heart or the energy to tell her that no, this wasn’t really any sort of comfort. She may as well have been whispering in the ear of a fly about the future survival of flydom a split second before it hit the windscreen of a delivery van.

She looked away momentarily to get a sense of the rest of his gloomy, lonely shop, and he found himself, quite involuntarily, trying to catch her gaze as she looked back. What on earth was that?

‘Look Ellie, I have a few questions myself, so how about I answer your questions honestly if you answer mine. I haven’t spoken to anyone properly in quite some time and, let’s be honest, I probably never will again.’

She paused.

‘What do you want to ask? And remember, this is super weird for me. Like talking to a hologram of Jesus would be for you.’

‘Religion’s not a bad place to start, actually. How’s that getting on?’

She opened a small electronic device, screwed up her face in a fashion he found intriguing and then snapped it shut.

‘What’s religion?’

‘Fair enough. How about politics? And before you take out your gadget again, it’s that thing where people all get together and elect other people to run their countries.’

‘What’s a country?’

Like the Betamax video recorder, erased from history, it seemed. He asked her about how time travel worked but her understanding of the quantum nuts and bolts was about the same as his grasp of how a Formula 1 car was put together, which was fair enough. She knew there was a shiny machine involved, a lot of noise and it cost a fortune.

‘Can I get on with my job now? I am a little short of time.’

Now he smiled at her.

‘On a scale of one to ten, how was your experience of the end of the world?’

‘Excuse me?’

‘On a scale of one to ten…’

‘No, no, I heard that bit, but what sort of answer do you expect to that? That it was a seven and the best thing that’s happened to me this week?’

Now that he came to think of it, that was about right. Here he was, the end of civilisation as we knew it, breathing hard down on his neck and what had he done? Got up, gone to work, opened the shop, kept calm and carried on. It was pathetic now that he thought of it. Had he gone out, gotten smashed, shook his fist against the sky, futile as that might have been?

‘Seven. It’s a seven. You’re not from the future, are you?’ he said gently.

She stopped while conflicting emotions flew across her face and her posture shifted slightly.

‘Maybe I am, Alan, or maybe I’m not. Maybe I was alone and terrified and angry and the world has uncontrollably emptied out around me.’

She swapped feet and her tone rose.

‘It’s possible I had no idea what I could do to stop myself going insane because my flatmate disappeared weeks ago so I could either hunker down there by myself and just fizzle out or get out, not die alone and just do something!’

She yelled the last two words as if they were a manifesto.

‘Bloody ‘Ellie’, what are you like…?’

Alan thought, not for the first time in his life, about what a gullible idiot he usually was. He also realised how alone he had been. For years.

‘If I was from here and now and let’s say, just a mediocre actor wanting to play one more silly part…’

She swung around gesturing as if she were onstage at The Globe.

‘…This makes sense, right? I’ve been staring out the window into the empty street outside thinking about all of this. The way we’ve all spent decades knowing we were destroying any chance we had as a species. Setting deadlines that went whizzing past while everyone presumed that the next one was the very last, last one we’d better aim for.’

Alan had the fleeting thought that if she were a politician, he would vote for her. Would have voted for her.

‘Treating bloody catastrophe like we were doing homework under the desk first thing on a Monday morning at the same time as the strictest science teacher you’ve ever seen came rumbling down the corridor.’

‘Probably closer to an eight now that I think of it…’ Alan tried to interject.

‘Except we hadn’t even tried to manage that, had we? Realistically, right up until four weeks ago, we were all still rummaging around in our schoolbag fumbling for a pen. We had all done nothing, including me.’

Her head dropped and she paused. She ran her fingers absentmindedly through her hair.

‘Maybe this is guilt, Alan, guilt that I had spent all that time knowing all about an end I could do something to change and yet did little to nothing to mitigate. Now I’m engulfed by an end I can do absolutely nothing about. Maybe I’ve gone properly stark raving mad. Don’t you ever feel that?’

Alan looked at the angry, passionate, compelling stranger standing in his shop. He was fairly sure he’d just felt what it might be like to have maybe met someone he might one day fall in love with.

Now, like her, Alan wanted to live.

But sadly, for everyone, it was too late.

Empty House, edited by Alice Kinsella and Nessa O’Mahony (Doire Press), is a multi-genre anthology of Irish and international writing responding to the climate crisis.

The leading challenge facing our world today, here writers share pieces that address what it is like to live in a world imperiled by climate chaos. Interpretations vary from celebrations of the natural world we are at risk of losing, anxious prophecies of the earth we may soon live in, to constructive hope of how we can prevent environmental catastrophe. Together they form rallying cry of human responses to a systemic problem. Contributors include Luka Bloom, Niamh Boyce, Jan Carson, Jane Clarke, Moyra Donaldson, Arnold Thomas Fanning, Rebecca Goss, Claire Hennessy, Lisa McInerney, Paula Meehan, Annemarie Ní Churreáin, Nuala O’Connor, Rick O’Shea, Jessica Traynor and Michael Viney.

Empty House is funded by the Arts Council of Northern Ireland. Both editors and Doire Press’ layout designer Lisa Frank have donated their fees for their work on Empty House to Friends of the Earth.

Launch info: Earth Day, Thursday April, 22nd, 7:30h

Livestreaming on Facebook, youtube and www.doirepress.com