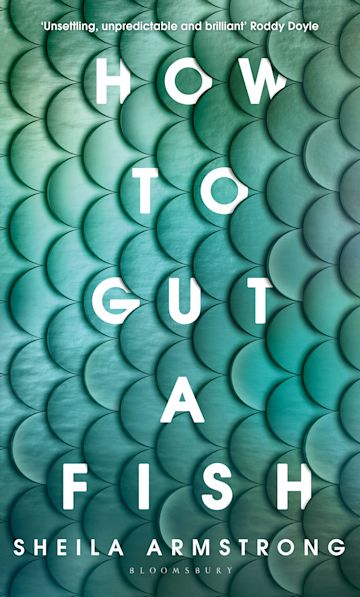

How to Gut a Fish|Sheila Armstrong|Bloomsbury|ISBN:9781526635778|€14.99

“…the knowledge of a world that is beautiful, terrible, ancient and sacred.”

—Laura King on How to Gut a Fish by Sheila Armstrong—stories that are a feast for the senses, suspenseful and disturbing.

by Laura King

How to Gut a Fish is vivid, original collection that takes as its main preoccupation the uneasy, troubled relationship between humans and the natural world.

Certain themes reappear, like a tongue running over an old wound: bodies, illness, motherhood, decay, fate, sacrifice, and ritual.

These strands run throughout the stories, criss-crossing in a complex web of mirrored and repeated images and ideas that echo through the collection, haunting the reader.

Discord

Throughout the collection, we see people in harmony, but more often at odds, with the natural world. In ‘Star Jelly’, Armstrong comes closest to stating an underlying message that, for all our supposed mastery of the world, humankind have gone too far in their greed and arrogance, and their contributions towards climate change are irreversible.

Humans are only transient inhabitants of the earth which is darker, more beautiful and more terrifying than they remember to respect.

Sacred space

The opening story, ‘Hole’, draws on the ancient world and cultural memory, and begins the collection by bridging a gap between the world as we know it and another side, accessible only through convening with that natural world.

Every line in ‘Hole’ is delicious and quotable, the “hungry” grass and shapeshifting birds, the air that “trembles like a bent sheet of tin”, a body piercing that is “a dark hole that swallows the moonlight”.

Humans are intruding on this sacred space; a badger sow is valued—if not more valued—as a protagonist because she respects the natural order, instead of trampling through sacred ground.

The closing, unsettling image of the “umbilical” connection swallowing the earth through the hole is a horrifying subversion of the otherwise positive images of motherhood throughout the collection, and is a disturbing allusion to mother nature—who has begun to retaliate against how humans are treating the earth.

Feast for the senses

The title story, ‘How to Gut a Fish’, is a feast for all the senses, but runs deeper to touch on wonder and fear.

There’s something of a sacrament to this story, grounded in bullet point instructions but drifting towards personal reflection, underpinned by ritual.

In a collection of earthy stories, this is in some ways the most vividly connected to the everyday business of living and dying, killing and surviving in the world.

A group of men on a stag weekend, shepherded to an island, are only too delighted to take time out of their ordinary lives to be “at one” in nature, and the island provides them with a survival fantasy that they can dip into when they choose, but they are never fully in control of the experience, or able to master “the great outdoors”.

There is something chilling about the ritual that is inverted later as the protagonist takes the place of the frightened, hunted animal. There is a constant tension between what is good and bad, natural and unnatural, and something that creeps between.

Suspenseful and disturbing

‘Red Market’ is an expertly crafted, suspenseful and disturbing standout of the collection.

In the first sentence we see men “dislodge piles of furniture like undigested chunks of bone”, and in the midst of all the hubbub of a busy weekend market just before Christmas, it is easy to miss this omen.

Alongside silk scarves, roasting trays, a diving suit, a young girl’s body is bound and displayed and auctioned off for parts.

The tone of the story and the sellers and customers at the market is extremely casual; the girl is one of many objects for sale. This dystopian marketplace is a far cry from the majestic sweeping landscapes and quiet earthy texture of the other stories, but is a harsh look at the horrible side of human nature, capitalism, and how the body is commodified.

The narrator interjects now and then, salt in the wound each time as the reader grapples with what is happening, to tell us how the highest bidders will go on to use the girl’s organs are each thwarted by accidents and coincidences that mean their investment goes to waste, as though fate is at work to punish those who go against the natural order in the name of greed.

Magic in the collection

Not only did I want to start the collection over again immediately upon finishing it, I had that urge after finishing every single story. I wanted to go back to the first page each time to figure out what exactly had just happened and what made each story tick once I wasn’t so caught up in it.

However, in many of the stories my awe and admiration kept winning out and I still couldn’t detach myself enough to really study them.

The book meets the reader only part-way, demanding not only further examination but reflection and introspection, inviting the reader into a conversation to fill in blanks, by way of the reader’s own emotion or point of view.

Armstrong’s writing is clever and exact, the stories are skilfully structured, the natural world is painted beautifully and the characters are carefully drawn.

However, the magic of the book is that it takes you out of your head and into the body, into what it feels and smells and tastes and knows, whether that is indescribable wonder at the beauty of the northern lights of the Wicklow mountains, the shock and pleasure of a sea swim, the fierce protectiveness of a mother, a creeping realisation that you feel in the back of the neck before you understand what’s going on—and the knowledge of a world that is beautiful, terrible, powerful, ancient and sacred.

Laura King works in publishing in Dublin, and in her spare time reviews books online under the name @lauraeatsbooks