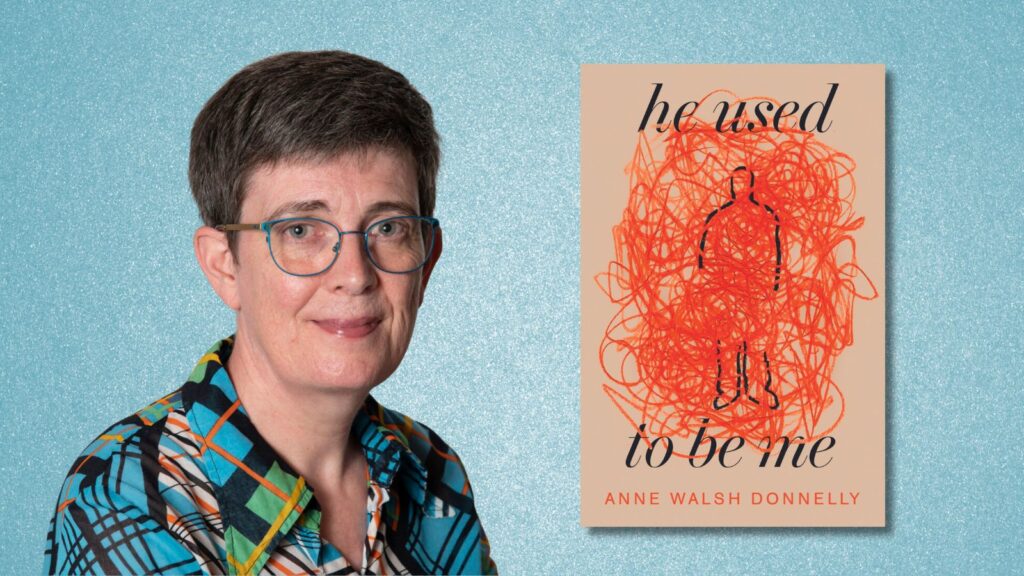

From poetry to short stories to her debut novel He Used to Be Me, Anne Walsh Donnelly “creates to live, to breathe”

by Catherine Murphy

Anne Walsh Donnelly writes from the heart. Words fall from her as they shape on the page, some moving to one side of an answer, some to the other, some a direct hit with a soft laugh. We talk about the book – really, we’re talking about so much more, but then, He Used to be Me is about so much more than the life of Daft Matt.

Whether it’s a symptom of welcoming her age, being over fifty, or a result of the intensity of life for everyone in the past few years, Donnelly has a way of seeing the world as if noticing it suddenly, in its true form.

She’s known as a poet, but in truth she’s as drawn to writing short prose and to novels, as she is to poetry. She rejects the idea that He Used to be Me has a poet’s feel, but the lyrical nature of her work is undeniable. She smiles as she speaks about writing poems, how some come to her fully formed, how she has to grab them at the moment of inspiration before they fade, writing in the car in Dunnes car park, or how others she will tweeze and edit and rework for ages until they feel right. Everything, for Donnelly, has its place. Every comma, every word, is considered.

Donnelly has a way of seeing the world as if noticing it suddenly, in its true form

She claims not to be an intellectual writer, but I argue the point. There is deeper meaning to everything Donnelly writes, even to the shape of the words on the page. The book went through many edits until she was satisfied with the layout but the text itself—the prose—hasn’t changed that much from conception, she says. Writing, for her, is part of being. From poetry to plays to short stories to this first novel, she creates to live, to breathe.

The character of Daft Matt has been with her for the past twelve years; she takes her time to get the story right, to stay true to the voice. A single parent, she’s appreciated the space life gave her when her children grew up, to know herself and to step back. Her creating comes from a place of separation and in a way, Matt’s story is one of moving aside from society, of seeing people and places from a distance.

The story begins with a jab to our conscience: “You call me Daft Matt. Daft old man. Say I’ve no face. You must think I’ve no ears either. I feel your eyes on me, staring at the crown of my head, lice playing hopscotch on my scalp and hump on my shoulders as big as Nephin mountain. I’m not as mad as you think.” We, as readers, become the witnesses.

From poetry to plays to short stories to this first novel, she creates to live, to breathe

Donnelly shows reflections, the telling of other people’s views of Daft Matt, of his life, his loves, his family, his tragedy, but it is his heart we feel beating in the book. As we read, we realise the erratic text profile shapes the fragmented nature not of his character but of the way his brain now works.

He’s a soft man, Matt. He loves passionately. He sees life not in black and white, but in light and dark. We follow him from a complicated and sometimes brutal childhood into a love that inevitably slips away from him, and then to a fall, an accident that changes everything.

There’s grace to the simplicity of the novel but also an incredible sadness, especially within this central turning point of the story. Suddenly, the disjointed paragraphs make sense – the alignment, the other voices. The bitter lines from the cága, the jackdaws, spike through his unhappiness. The solace that Matt had once found in nature is now cruel, his home no longer a home.

Donnelly understands the sadness but she also finds beauty in how she expresses that grief

Instead, he faces isolation within his daftness. His institutionalised living in the second half of the book becomes small, his family—the people for whom he’s lived and breathed—are no longer a real part of his life, only his memories. With his one reconnection to them, his figure is tragic and messy, and the reading there is uncomfortable in its tenderness.

Loss runs mean through the story. Donnelly understands the sadness but she also finds beauty in how she expresses that grief. Donnelly loves Matt, this comes thick and fast from the pages. There are clear threads between them and she talks about having lived alongside him and his story.

She’s working on more of a reflective piece now, memoir based, exploring universal themes. She doesn’t write to formula but she doesn’t need to, she has carved her own way. She listens and she recreates her world, from her rural upbringing to her life-earned experiences in coming out as gay, at fifty.

Like the shape of the words on the page, she needs the shape of her career to be right

She speaks fondly of her children, now both at college, and of her father; the stark comparison between her life and Matt’s feels like a concrete line in the sand. Matt becomes daft. He feels the judgement of others. She loves him the more. Donnelly talks about her close family and her characters with the same affection, with the closeness Matt is so clearly missing.

Donnelly talks about going through a time without writing. She missed it desperately, but life is short. She wants to be kinder to herself. She feels the pressure now to produce another novel, but she’s holding back. Like the shape of the words on the page, she needs the shape of her career to be right. She’s torn, knowing the world is hungry for more stories, but she’s controlled. She likes to work in fragments. She has the next character buzzing around in her head but she’s waiting, she’s not going to force anything.

Anne Walsh Donnelly walks her own path. Passionate about the story, she feels He Used to Be Me is her best work to date. I suspect the best is yet to come.

Catherine lives on the very westerly edge of Co Clare, surrounded by cows. Writing both as C L Murphy and Kitty Murphy, she divides her time between sparklingly stabby murder mysteries and darker, literary tales.

Catherine is represented by Ed Wilson at Johnson and Alcock.