In this interview, humanist, poet and writer, Dolores Walsh Questions a Franciscan on his recent controversial book, ‘St Francis Uncensored’

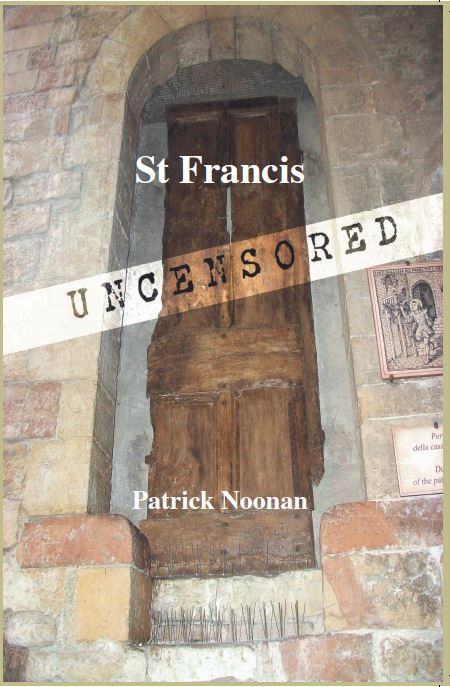

DOLORES: Pat, I don’t usually read about saints in the Roman Catholic Church but your book’s title is interesting and suggests you might be stepping “outside the pale” of the church. The image on the cover of the coffin-like door of Francis’ ancient home in Italy conjures notions of life housing death. What’s so important about Francis of Assisi in light of the kind of world we live in today? Personally I’m more drawn to looking at what Peter Singer the moral philosopher and writers like Doris Lessing, Antoine de Saint-Exupery, Zora Neale Hurston and Margaret Atwood have to say. So why did you write this book? What is it you think people need to hear about this man from the Middle Ages?

PAT: Well, one morning I was sitting in an empty church before what we call the Blessed Sacrament when I had a sudden moment of clarity: Why do ordinary parishioners today in the Western world only remember St Francis as the saint who loved animals? Pretty boring, don’t you think? And this after centuries of research on his life and times. Plus I knew I hadn’t become a Franciscan because of animals! Don’t get me wrong, Dolores, animals love me and I them. Exposed to numerous species over my many years living in Africa I sometimes think I might even have talent as an animal whisperer!

DOLORES: And that moment of clarity….?

PAT: Yes, it dawned on me that my image of St Francis was outgrowing the image I had received at the seminary. I began to compare the world I was living in and the type of “Third World” St Francis embraced after he left home. I found close connections between the two worlds so far apart in time and space. I found myself questioning prevailing stereotypes of Francis and indeed St Clare, his contemporary, also born in Assisi. For instance I was never told that the highly innovative Clare was one of the most liberated women in human history. Against all the odds she dared to explore outside the box the heretofore unknown in religious life. She was one of those amazing people who start religious orders. Gathering my thoughts together in this book was a way of processing my reflections.

DOLORES: You portray this man Francis as politically-minded, a loose cannon in the medieval church, a non-conformist, a rebel, a nuisance, not an image the nuns I was taught by, ever touched on.

PAT: Yes. And then in the middle of everything along comes a woman called Clare to complicate his life and make the reader wonder about their love affair.

DOLORES: Did you intend to be provocative in the way you handled their story?

PAT: I’m not sure about that. However, their story is a great story and I wanted to tell it in a lucid way, while engaging the reader’s attention. The book was a process. I remember one evening I sat down to the laptop and suddenly I was changing all the chapter headings. From churchy, passive, academic-style headings to vibrant, eye catching, more daring ones. I was breathless when it was all over. And the Francis you get initially in the book is very romantic, a flirt, someone who laughs loudly (like happy, over-excited millennials in Coca Cola ads), a sort of regular carefree socialite hanging out with the guys. I might mention that this volume was never intended to be a beginner’s life of St Francis. It’s coming from another space, a different place. A place where you are happy and comfortable to acknowledge that St Francis was a loyal, creative, independent-minded, globetrotting mystic with a broken line to God. Most saints are like that. In fact to understand Francis it would be helpful to be a mystic like him. It’d also help to have some understanding of the “third world” culture Francis chose to follow after his chance encounter with lepers. Most converts even today have similar testimonies of born-again experiences.

DOLORES: Then he goes to war as a soldier and ends up a prisoner in solitary confinement for a year.

PAT: True, in a dark putrid medieval dungeon. After that everything changes. He becomes a lonely figure, detached, a dishevelled drifter, sometimes very quiet, emotional, outwardly awkward, often with solitary ways. And later he becomes a runaway teenager, a daring traveller, later still, a person who talked to power in Italy and Egypt.

DOLORES: Quite an arc to his life, setting his love of animal’s aside….

PAT: Yes, this is much of what Francis was: scattered, holy, impulsive and impossible. You just can’t ignore him on the world stage.

DOLORES: It’s refreshing to read work by a priest who tries to interpret political matters and appreciates the interconnectedness of all beings, of all things. Francis, you feel, had that in him too. I see you explore themes like dreams, relationships, betrayal, revenge, violence, murder and war. This book ranges far and encompasses many things.

PAT: Yes, who needs Harry Potter when Francis Bernadone has been there, and has the T-Shirt to prove it! Francis comes out of that crazy mix. I’m wondering would he be acceptable for religious life today! But seriously in planning the book I tried to bring Francis’ story emotionally and personally alive.

DOLORES: I think you achieved that, your chapters are short and vivid. And despite wincing at your depiction of “adoring maidens” pursuing Francis and some priest having a “comely girlfriend” – phrases which bring to mind De Valera’s 1943 broadcast – I was stunned to learn that when Clare stood up to the Pope, it was in an era when “many great thinkers and renowned theologians wondered whether women had souls at all; whether they were a divine mistake or even ‘failed conceptions.’” You hit hard there. Though given the history of the church’s attitude towards women, I don’t know why that revelation surprised me.

PAT: On the world stage there were even more well-known women thinkers who were leaders than Clare, such as Hildegard of Bingen (12th century), Catherine of Sienna (14th century) and Theresa of Avila (16th century). Among many other accomplishments all these leaders were courageous writers whose works are still selling today. It made me think of the seeming contradictions in the church. And my book doesn’t give a romantic or sentimental depiction of either Clare or Francis of Assisi or of the time they lived in. There may be readers who will find some of the contents upsetting.

DOLORES: For instance, Francis and the American gun lobby?

PAT: Yes, in imaginary confrontation with them. Many gun-toters, including Catholic ones, in present day America will not be impressed with his attitude to arms carrying. It was controversial even in his day. It reminds me of the time my former parish in South Africa became a local depot for collecting illegal arms during a nineties’ post-apartheid amnesty campaign. I wonder could that be done in the United States today?

DOLORES: Do you think living and working and missionizing outside of Ireland has enabled you to write this book in a way you couldn’t have at home?

PAT: Definitely. This book could never have been written in Ireland. It’s based too much on foreign experiences, non-European personal and social encounters. More immediately it emerges from the traumatic experiences of friars living through three liberation wars in the past century: in El Salvador, Zimbabwe and South Africa. In the seventies and eighties Franciscan missionaries lived with the oppressed during revolutions in the favelas and mountains of El Salvador. They also ministered to the Vakomana (freedom fighters) in the forests of Zimbabwe and on the burning streets of Sharpeville in South Africa they blessed the boycotts that drove the collapse of Apartheid. Francis knew this type of conflict for he too did military service in the blood stained hills and valleys of Perugia, central Italy.

It also reminds me of the criminal treatment and public hangings of Franciscans and many other clergy (victims of paid priest hunters) in the towns and cities of Ireland during Penal persecutions in the sixteenth century. The Sherrif of Westmeath in 1600 prompted by Queen Elizabeth 1 of England called the Franciscan community at Multyfarnham in Westmeath “a nest of scorpions” as a prelude to burning down the friary and arresting those friars who didn’t escape. Historic events from the peripheries of society – including The Fifth Crusade in Egypt which shaped St Francis – also shape the thinking of Pope Francis today and are an essential backdrop to this narrative.

DOLORES: At the beginning of the book you re-imagine the parents of Francis in a modern, contemporary setting giving an evening news “television” interview after he ran away from home. It was innovative and vividly imagined even down to the description on their faces. You seemed drawn to the parents of Francis, to expressing the universality of their pain at his loss?

PAT: Yes. It’s true. A life size statue of Francis’ parents is to be seen in Assisi today. The sculptor depicts a very distraught couple. Francis their son had gone missing. They wondered privately was it a religious cult he had joined. People who espouse political or religious causes often leave their families in turmoil. The day I left to join the Franciscans my father disappeared into an empty city church to sit down and try and come to terms with it. My mother wondered why I hadn’t gone after a job at Players cigarette factory and later take over the family business. I wanted to explore that element a little more in the life of the saint. Francis was a good context and a tested subject. His parent’s story is often passed over too easily.

DOLORES: Your passion for bringing Francis to life was very moving at times. As you know, Pat, I don’t believe at all in the institutional church, its doctrines, rules, its exclusion of women priests and I abhor its continued suppression of clerical abuse in so many cases today in the world. What interests me here in your book is that Francis was also reacting to terrible scandals in the church in his time.

PAT: That’s true. It was like as if God had parachuted Francis into the Papal States (an army Commander-in-Chief Pope is a scandal in itself by our standards today!) behind enemy lines to disrupt their supply chains of corruption, and to highlight an alternative way of life. Assisi itself, Francis’ birthplace, was split between those who stayed in the church and those who left and became Albigenseans. Though I don’t know if the word “scandal” was used to describe these things at the time.

Let me add something else here, Dolores, that is an essential part of St Francis. It has been elaborately treated by other writers down through the centuries. Francis nurtured a deep inner mystical life that only a few of his friends knew about. The Eucharist, intense meditations in caves and charismatic prayer, the awesomeness of the Trinity, the originality of the crib (creative representation before Hollywood existed!), and Mother Mary captured his imagination. And the whole event of a Christ figure walking the roads and streets of Palestine (Ghandi-like) two thousand years ago wanting to save a vicious, bloody (Herod was a serial killer) world profoundly moved him like there was no tomorrow.

If you had received the marks of Christ on your body, the stigmata, you too might feel conflicted. For Francis there was no God question. Even after all the violence and bloodshed he had experienced. His whole life was the God slot. It’s been my experience that people living on the margins of the world never seem to question the existence of God even today.

DOLORES: Part Two of your book is entitled “St Francis and Jihad.” In it, you recount how Francis, during one of the Crusades in the thirteenth century, armed with nothing but his courage, went uninvited behind enemy lines to meet an Islamic leader. Just what did he intend by doing this?

PAT: Yes, to meet the ISIS of his day. Not as a politician but as a religious figure on a mission. Perhaps Francis knew something we haven’t yet learned as human beings that made him feel the risk was worthwhile. Did he really think he could persuade the Muslim leaders not to destroy the Holy Places in Palestine? Perhaps he had he heard that you “could do business” with this Sultan? That Sultan Malik al-Kamil, leader of the Muslin forces was a sincere person of faith? The accounts vary.

In fact, this year is the 800th anniversary of that encounter. Powerful and relevant stuff. And I’ve been surprised by the reaction to the chapters on those two momentous weeks Francis spent in northern Africa during the Fifth Crusade at Damietta. Let me say it in another way. Recently in Johannesburg I was invited to an interfaith screening of a new film called The Sultan and the Saint. About fifty Muslims attended the showing by an ecumenical Islamic group called Turquoise Harmony Institute who follow the Gulan school of tolerance teaching. After the show with the greatest humility I suggested to the assembly that the scriptwriters and producer must have read my recent book, St Francis Uncensored. We had a good laugh at that. Muslims and Christians alike can share a joke. And it’s not by accident that Franciscans have an international house in Istanbul today, the homeland of Rumi the Islamic mystic, poet, admirer and contemporary of St Francis.

DOLORES: A soldier who became a pacifist, and who, as you say in your book, walked the talk.

PAT: For sure. St Francis is a man without borders.

Dolores Walshe, author of Where the Trees Weep, has won many awards for her writing, most recent of which is The Berlin Writing Prize and a Creative Frame Leitrim Arts Award. She is based in Carrick-on-Shannon, Irelandes

Patrick Noonan ofm is also the author of books on aspects of parish ministry including “They’re Burning the Churches” (Jacana) read twice on South African radio. Noonan’s most recent books include “Township God” and “Help! My Granny’s Dog is a Racist” (Write-on Publishing). Website: www.patricknoonanbooks.org.za