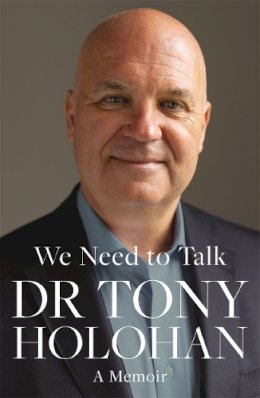

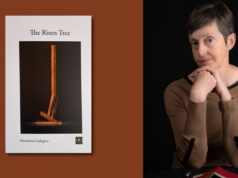

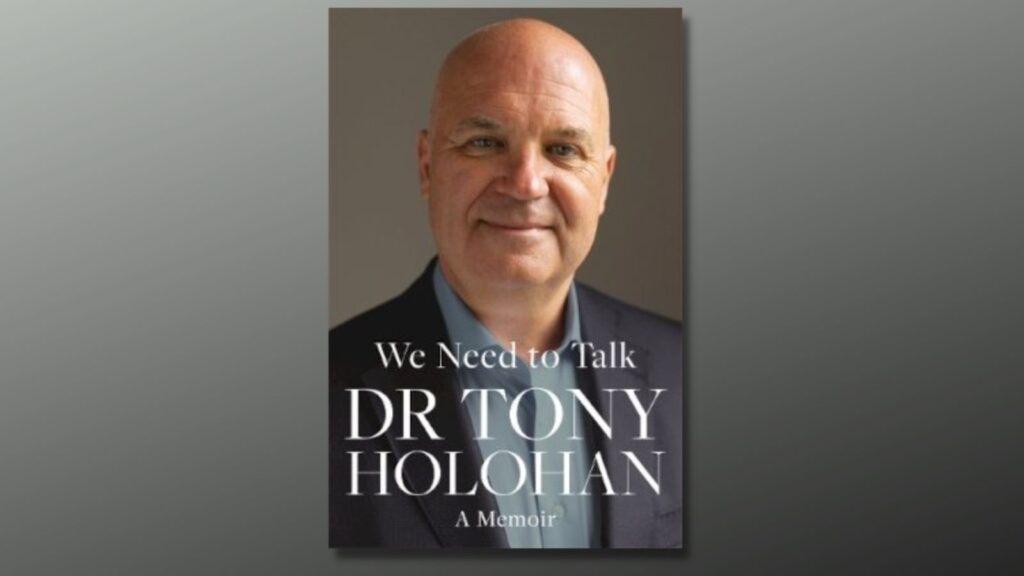

A Battle on Two Fronts—We Need to Talk, by Dr Tony Holohan

We Need to Talk| Dr Tony Holohan|Eriu|€18.49

by John Kirkaldy

Few people in Ireland will need to be told the identity of the face on the front of this book. Dr. Tony Holohan was Ireland’s Chief Medical Officer (CMO) for fourteen years. During the Covid epidemic, he was on the nation’s television screens and in other media on a very regular basis. Fergal Bowers described him as being ‘as familiar as Dr Anthony Fauci in the US and arguably as influential.’

This is largely a record of a battle on two fronts. Holohan’s account of his time as CMO, as head of Ireland’s public health strategy, especially during Covid; while at the same trying to cope with the fact that his beloved wife of 25 years, Emer, was the victim of multiple myeloma. He comments as CMO, doctor and husband: ‘Myeloma is incurable. Once that diagnosis is given, it is only a matter of time. And often, not very much time.’

There is also some personal biography of the Limerick raised boy, who went on to study medicine at UCD and decided to specialise in public health. In his first week at university, he met Emer, who was also studying medicine, and was immediately struck.

The Covid crisis

He was lucky that when he was appointed CMO in 2008 (he had been Deputy for six years) he was in position well before Covid struck in 2020. He at least knew some of the ropes in dealing with controversial public health debates. He details with honesty events and policy surrounding the Swine Flu and CervicalCheck crises.

Virtually everybody reading this will have a view of how Ireland handled the Covid crisis, one that is, of course, not yet quite finally over

He is critical of Minister of Health, Simon Harris, who he says pushed to establish an immediate investigation into the misreading of cervical smears against his advice. He described CervicalCheck as a ‘perfect storm,’ arguing that from the beginning there was ‘confusion, misinformation and disinformation.’ Holohan was a sympathetic supporter of the process and verdict of the Abortion Referendum of 2018.

Virtually everybody reading this will have a view of how Ireland handled the Covid crisis, one that is, of course, not yet quite finally over. It certainly did better than the neighbouring UK, where the handling of Covid was a major factor in the downfall of Boris Johnson.

Controversy

If Ireland won some international plaudits for its handling of the crisis (in September 2021, the country came top in the Bloomberg Covid resilience table), it was often a bumpy and controversial ride.

Holohan, as Chair of the National Public Health Emergency Team (NPHET), recommended that hospitality be closed over December 2020/January 2021. The Government, however, reopened pubs and restaurants in the hope of giving what the then Taoiseach, Michaél Martin described as ‘a meaningful Christmas.’ Holohan comments: ‘There were more than 1500 Covid deaths in January 2021. It was the single worst month for deaths over the entire course of the pandemic.’

In a strong defence of NPHET’s decisions, Holohan disputes suggestions that Ireland’s long lockdowns were the result of a low number of Intensive Care Units (ICUs)

He was particularly hurt by remarks on television from Tánaiste, Leo Varadkar, who claimed that ‘members of NPHET were insulated from the effects of the advice we gave…Emer was slowly dying and would be cut off from all her family and friends in her last few months of life.’

In a strong defence of NPHET’s decisions, Holohan disputes suggestions that Ireland’s long lockdowns were the result of a low number of Intensive Care Units (ICUs). He argues that even with more intensive care beds, they would not have substantially changed their advice. ‘We would still have done everything we could to prevent people ending up in ICU in the first place,’ he writes.

In general, Holohan had a good relationship with Harris, when Minister of Health. ‘He was very supportive of the public health advice both in public and behind the scenes.’ It is interesting to note that Holohan insisted that Harris and his successor, Stephen Donnelly, should not attend meetings of NPHET meetings, when discussing policy. ‘It was necessary that the Minister not be in the room where part of the process that formulated that advice was undertaken.’

He also emphasised the importance of all members of NPHET complying with the regulations

Holohan also provides some strong opinions on other aspects of the crisis. Based on his experience from previous crises, he emphasised the centrality of fact-based policy. It was essential that the public regularly received good quality advice, ‘which could be understood, effectively implemented and monitored and ultimately relied upon.’ He writes that he felt that in the media, ‘there was too much intolerance of these understandable and often isolated examples of non-compliance.’ The whole emphasis should be on encouraging responsibility.

He also emphasised the importance of all members of NPHET complying with the regulations (Boris, please note). ‘There were no incidents that I know of in which we NPHET members were identified as not following the advice.’ The family teenagers, Clodagh and Ronan, did not let their father down! Overwhelmingly, the vast majority of Ireland complied, but Holohan is critical of those commentators with little or no medical background, who were given publicity. He calls the sometimes-held view that there is an acceptable level of deaths, ‘despicable.’

Pain and loss

Interlaced with this analysis of Ireland’s worst health crisis is a very moving account of the death of Emer. She was diagnosed in September 2012 and died in February 2021. It is a haunting testimony to a brave and much-loved wife and mother. The pain and suffering increased immensely over the years. ‘When I met her first, she was tall – five foot eleven – and so striking looking, I would say that she was five foot five or six when she died.’

Interlaced with this analysis of Ireland’s worst health crisis is a very moving account of the death of Emer.

The details of Emer’s decline make for harrowing details. What comes through is a loving and brave woman, who, even at the end was anxious for the well being of her family. An additional dimension was that, as both were doctors, they were well aware of what was going on. Holohan explains: ‘I realised that it wouldn’t be right for me to try to be Emer’s ‘doctor’…I was the only person who could be her husband.’ (He did have leave of absence in the period July-October 2020.)

Emer wrote letters to her close friends and relatives and talked endlessly with her husband, immediate family and children. Holohan emphasises that Emer received no special treatment and her funeral was conducted along strict Covid regulations. At her death bed, only husband and children were present.

This will not be the last word on Covid but it is a very important contribution from a man at the very heart of policy making. It is written in clear and jargon-free English. Emer discussed with her husband what should happen after she died. She urged him to find happiness with a successor and he is now ‘in a loving relationship with Ciara Cronin.’

This will not be the last word on Covid but it is a very important contribution from a man at the very heart of policy making

Holohan resigned as CMO in July 2022. A plan to second him to be Professor of Public Health at TCD fell into political choppy waters; he puts his case with convincing vigour. He is now Adjunct Full Professor of Public Health at UCD and a Non-Executive Board Member of the Irish Hospice Foundation.

There is only one epidemic that Dr Holohan seems unable to cure. Along with paramilitaries and the armed forces, public health is notorious for acronyms. This book deserves a second edition but please can the author and publisher put a glossary at the front?

We Need to Talk| Dr Tony Holohan|Eriu|€18.49

John Kirkaldy has a PhD in Irish History, worked for many years with the Open University and has been reviewing for Books Ireland since 1980. He has contributed to three Irish history anthologies, a school textbook, and has been involved in a number of Open University History documentary series. Aged 70, five years ago, he went round the world on a much delayed gap year described in his book, I’ve Got a Metal Knee: a 70-Year Old’s Gap Year.