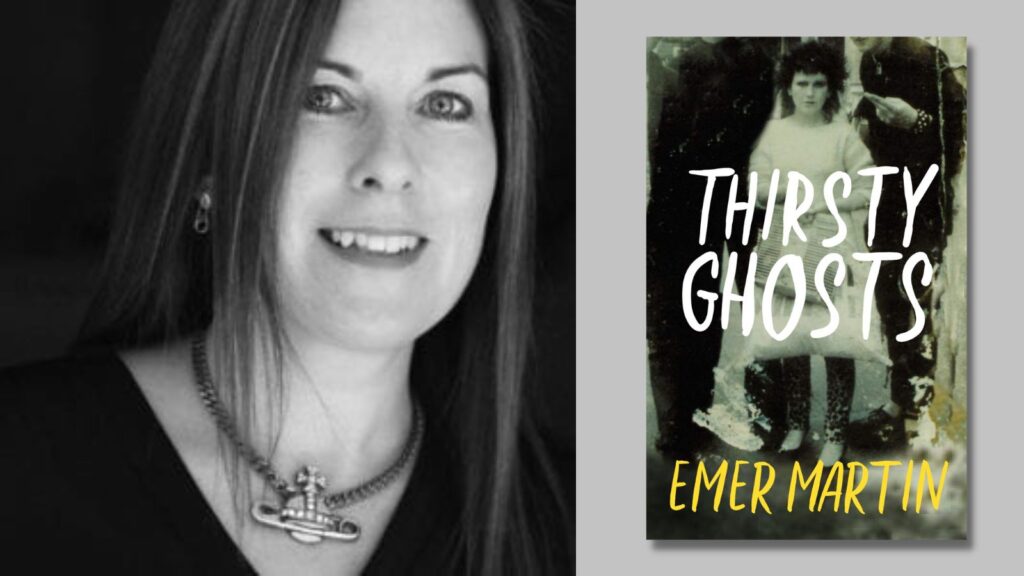

“Stories are medicine, I believe they can heal us”—Catherine Murphy talks to Emer Martin about her new novel, Thirsty Ghosts (Lilliput Press)

Find Thirsty Ghosts at our featured bookshop for September, Chapters Bookstore

by Catherine Murphy

Emer Martin knows how to tell a story. We chat on Zoom, drinking from mismatched mugs. She has her nails painted and she gestures with her hands; there’s a swirling picture on the wall behind her, bright oranges and yellows, and as she talks about the characters in her book, the families, the myths, the legends, it’s almost like she’s sitting by a fire, speaking our history, the stories she has woven through this book.

My tea is cold.

Martin’s writing has a well-earned reputation of literary merit. Her latest, Thirsty Ghosts (Lilliput Press) is an epic work of multigenerational lived truth. It follows two families, and the hag—Ireland. It’s angry, beautiful and important.

She wrote this book, she says, to learn more about the legends and myths that make us. She’s fascinated by the worlds, by the clashes, our history. Thirsty Ghosts, like The Cruetly Men before it, tells about the inhumane torture of Irish women and children, from the atrocities of Essex to the Industrial Schools and the Laundries to the hands of families who followed a path without question.

Martin sees the ghosts. She gives voice to people who weren’t listened to, and that’s what makes this book so incredibly powerful. She shows us what a difference it makes to be poor, to be rich, to be impotent against the evils.

She wrote this book, she says, to learn more about the legends and myths that make us. She’s fascinated by the worlds, by the clashes, our history

Politics are laced through the text and through Emer Martin’s conversation. She’s animated, she’s frustrated. Her fingers grab in the air for the words. She is done with injustice—and rightly so—and that anger sits no more clearly than with the character of the hag: Ireland.

The hag

In the hag, Martin takes her passionate rage and celebrates the strength and power of women. The other stories twist and turn, but the hag is always constant, prickled, damaged, annoyed at how she’s been treated as a woman, and as our spiritual home, our country.

“She’s there in her full power as an old woman,” she says. “The hag comes through in moments and then I have to grab her and write that down. It’s almost like I have to meditate to get the hag.”

In the hag, Martin takes her passionate rage and celebrates the strength and power of women

The hag is the true heart of Ireland, the power of the ancient and the knowledge of our elders. She is love, earth, and soul. The hag chapters are like poetry:

Oh, hollow hag, I sink into your wound and it closes over me until I’m sealed, trapped like a stone in a scar. Yestreen my blood river in the grasses, drowned underground. They sink me down. Over before I was over.

I had to become nothing for you all.

Stories

A full, layered tale, the book moves swiftly between stories, and a wide cast tells this line of Ireland’s history. It’s the day after the launch and Martin talks about her family and friends who joined her to celebrate, and then she speaks with the same fondness for the characters in the book. She tells of a real-life aunt who loves stories, of rural magic, of witches and of a fairy tree—and then of Mary, the fictional aunt, the keeper of stories.

She smiles, switching between the book and reality.

She speaks keenly about what makes Ireland special, that we have to remember where we came from. She worries that without our stories, we will disappear and lose who we are, “become absorbed into this global world.”

“We are unique. We are a special place.”

She speaks keenly about what makes Ireland special, that we have to remember where we came from

Throughout the novel there are little nods for those who grew up in Ireland in the 70s and 80s, and those who love the country. From Shergar to pub banter, there’s humour, and Martin writes the comedy with a traditionally dark edge. Living in California now, she chuckles about toning down that darkness for her American friends. Her neighbours there have a baby who’s allergic to their dog and she says the solution is easy, you have to get rid of the baby—they love that dog!

I laugh.

Behind her, the not-fire-painting crackles and turns; we get it, they don’t. Isn’t that the curl of the joke?

Truth

We’re never so amused than when we’re laughing at ourselves but Martin holds an uncompromising tenderness to the truth. Within the magic of the folk tales and the legends, she never forgets reality. The title—Thirsty Ghosts—darts between the different stories with the same meaning: the souls that are lost and needy, heated and quiet; those who suffer without name; the families who battle the authorities on every side; the children who witness violence; the women who love, and lose.

The story is desperately real and there is a brutality to the beauty of the prose

As Dymphna’s story pulls in around the bitter, desperate sorrow of heroin addiction, the title takes on a new shine. Dymphna is pulled away from her family and thrown to the nuns. She escapes, only to fall into the arms of a violent pimp, to slip into prostitution. The story is desperately real and there is a brutality to the beauty of the prose.

Martin’s voice is quiet when she talks about Dymphna, about her research reading the reports on the Magdalene Laundries. On the streets of Dublin, Dymphna and Zoz see it all.

“It’s always the people at the bottom,” she says, “who can see everything. The powerful are so wrapped in their own privilege and power, they don’t really see what’s happening.”

Martin is struck by the way power has been taken from women. We come back to this again and again in the book, but the anger here isn’t flailing or melodramatic. It’s quiet. It’s raw. It’s a resistance, even in the knowing of its own strength.

The armies facing each character may be greater than they can take—from Essex to the nuns to the government to the police to heroin—but that doesn’t mean they stop fighting. Terrible injustice is shown, but under the blood and the suffering, for each one of them, is a hope.

It may be a stolen torc, or a story, or a bird, or an aunt, or a name and a place to be buried.

The gates of limbo are different to the gates of hell.

The characters are each given their strengths, and their sorrows.

Magdalene Laundries

Then there’s Bright, the little nothing-soul who was delivered to the Industrial School alongside the Magdalene Laundry and then on to the Laundry itself, her own life empty from want of never knowing what was outside the walls.

Ye are the rubbish of Ireland.

The chapters set in the Magdalene Laundries are heart breaking. The evil done there is scored in every page. It’s the quiet that echoes so deeply; the women are silent, even their names taken, only the softly whispered stories from Maeve / Teresa to comfort.

Again, in the nuns, we see power used to abuse. Again, Martin shines a light on what was so deeply wrong.

The storytellers take pride in their craft and they spin that small hope into the world

Martin’s characters bore the brunt of history. She talks about people who spoke their truth and weren’t heard, and the unchecked power of the church and the state. “People knew but they didn’t want to know.”

A razor tide cut the silk soles of your bare feet. Salt blood-pink in the foam mingled like a spell, right where water met land. Your firefly lives shine and blink out, yet you eat into time and leave so much behind. Your legacy is pain and wonder, always striving to alter yourselves and manipulate me. You can see so much, but you will never understand how you are blind. Even pigs can see the wind.

Myths and legends are gifts, from the earthly beginnings to the stories told by Teresa, then by Dymphna to her children, who fade so quickly from her life as heroin takes their place, and on with the other characters. The storytellers take pride in their craft and they spin that small hope into the world.

Resistance

The ghosts haunt the streets of Dublin, their souls thin. Emer shows us that for those who have nothing, hope is everything. She holds that passion in her creativity, using it to shape her stories, and she teases, she takes the very tip of the thread and dangles it lightly in the reader’s mind—she waits for us to take hold, and then when we’re relaxed, she pulls, hard.

Heads on spikes we were, a warning. Talkin’ away, not looking down. Not knowing everything is gone from us except our bad thoughts.

She’s quick and funny, and Martin holds the sweet mix both of growing up in Ireland and of now living away in the States, and looking back. She’s seeing us without the filters we carry. She sees the pain and the politics, the drugs, the violence, and the way families rip apart. And she sees the love—Thirsty Ghosts is very much about love, even if it’s the space where love ought to be. Emer is a political person. Telling our stories is resistance, she says.

Martin holds the sweet mix both of growing up in Ireland and of now living away in the States

“Stories became so powerful because when you think, we couldn’t have painters, and the musicians—they burned all the harps—but stories, we could keep those away from the powerful. They couldn’t take them. They were passed generation to generation. They’re really precious to me…I believe that stories are medicine. They can heal us.”

Emer Martin is holding her characters, her families, her stories, by the fire-painting that isn’t a fire, cradling them safely. In my mind, she will tuck them around her and bring them on, to the next generation.

Thirsty Ghosts is a keeper of stories.

Thirsty Ghosts|Emer Martin|Lilliput Press|€18

Catherine Murphy