A Poet in the House: Patrick Kavanagh at Priory Grove|Elizabeth O’Toole |Lilliput Press|€15

by Una Agnew

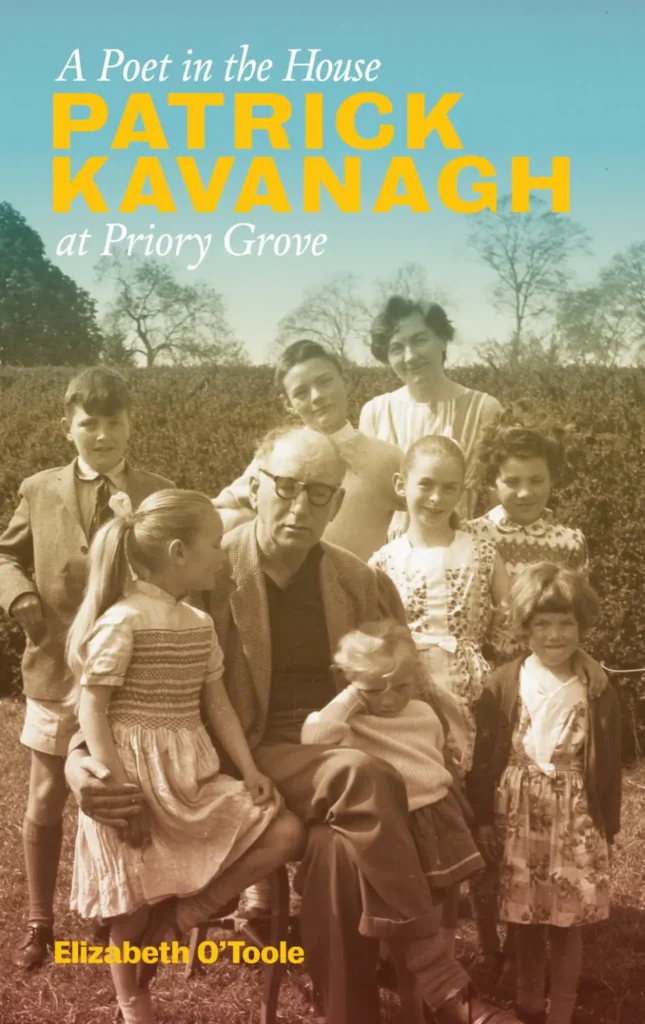

A hitherto unseen photograph of Patrick Kavanagh in A Poet in the House shows him surrounded by the O’Toole children, offering a different presence to the familiar, rugged personality of our esteemed national poet.

Here is a man content and at ease, as if proudly surrounded by his own grandchildren.

The photo dates from 1961 or 1962 when Kavanagh was suffering the after-effects of lung cancer with a tendency towards bouts of pneumonia. It was in such a state that Jimmy O’Toole brought him to his home one late, wet, December evening.

Heart-warming

A Poet in the House is a heart-warming account of Patrick Kavanagh’s recovery and prolonged stay at 47, Priory Grove, Stillorgan, where Betty O’Toole, ex-teacher, and full-time homemaker, shares her memories of the poet’s extended presence in her home.

She is now in her 97th year, living in Newton, Massachusetts, USA, happy that her story has at last come to print, thanks to the support of her daughter Margot and the industry and tenacity of its editor Brian Lynch.

Mutual appreciation

Quickly recovered from his run-down state, thanks to the consummate care provided by Betty and the O’Toole family, something of the inner refinement of Kavanagh’s soul surfaces.

True, he must be at first ‘tamed’ into proper respect for his hostess, whom he initially addresses as ‘Woman’ when he wants his porridge re-heated.

Soon, however, a mutual appreciation develops, thanks to Betty’s no-nonsense approach, her excellent cooking, and the amazing largesse of her husband Jimmy.

The O’Toole children

Ultimately, we see a contented poet, wrapped affectionately in the company of the children he never had, relishing a domestic ambience that was sorely missing in his own life.

His successful integration into a happy domestic life may surprise his critics who often see only a rough uncouth man who happened to write beautiful poetry.

The O’Toole children delight in the daily presence of a poet in their midst and play a considerable role in the poet’s rehabilitation.

Ranging in age from ten to two, Kavanagh engages with each differently, delighting in their innocent questions, and adopting his new role as pater familias.

He thrives on the presence of children around him, and his daily encounter with “the luxury of a child’s soul”, coupled no doubt with Pembroke-road memories of “playing through the railings with little children/ Whose children have long since died. His poignant awaiting the children’s return from school, shows a loneliness and hunger for the innocent forthrightness of children.

Writing

Quick to recover his strength, Kavanagh’s old typewriter is assigned a spot by Betty on the dining room table. She knows he must continue to do what he is meant to do—write.

Despite her busy household and mothering duties, she listens to his compositions while he is engaged in writing his weekly contribution to the Farmers’ Journal, whose headquarters was then at Harcourt Street.

Eight-year-old Margot, self-appointed writer’s assistant, is instructed to travel with her father, to deliver a now overdue weekly column. She is warned not to leave without the five-pound fee held firmly in her hand even before releasing Kavanagh’s envelope to the editor, which I believe was Paddy O’Keeffe.[1]

An instructive presence

A well-recovered Kavanagh on one occasion uses his shoemaking tools and skills when his cherished last is retrieved from his previous flat, making repairs on ten-year-old Larry’s shoes.

There is a further hilarious episode that tells of the recovery of Larry’s stolen bicycle in a manner typical of Kavanagh’s ingenuity in dealing with local thieves.

Kavanagh or ‘Paddy’ as the children affectionately called him, was an instructive presence for the O’Toole children who loved to spend their afternoons with him after school.

‘” Paddy and me” want to know’ was Elly May’s customary way of finding out when the tea was ready. Betty herself quietly observed her guest’s assumed role as teacher, and his simple explanations of God’s presence in the universe.

His God consciousness she found more all-pervasive than any she had ever known.

The child in Kavanagh

One senses that the child in Kavanagh found full expression in joining in the children’s games. His rush to spend his winnings at Punchestown races on a menagerie of Maggi-Man toys to bring them home and set up a play-area in the O’Toole hallway was typical of Kavanagh.

His capacity to be ‘lost in unthinking joy’ seems unquenchable.

One scene especially confirms qualities in the poet that tally with my own study of the poet.

One bright spring day when Kavanagh and Betty are returning from grocery shopping in Stillorgan, Kavanagh stops and requests they rest a while. He suggests they stretch out fully on the grass and feel the rhythm of the earth beneath them.

‘Listen’ he said ‘you can hear the grass growing and the wind calling the earth to life ‘. This, along with his ongoing conversation with the children regarding God’s presence everywhere—in the grass, in wildflowers, in weeds—is so recognisably ‘Kavanagh’ that it confirms for me the integrity of this memoir.

Back to health

In short, the O‘Toole household, especially the children, nursed the poet back to health at a time when he was virtually homeless and in poor physical condition.

His readiness to read from his New Poems (1950), especially his poem “The One” that Elly May could soon recite by heart, underlines his prolific unselfconscious God-talk, and his growing realisation at that time that he had already fulfilled his mission as a poet.

Allusions to his near drowning episode on the canal, his lost lawsuit against the Leader, his UCD lectures are all recounted as well as a highly ludicrous episode dealing with Kavanagh’s role as Judge for the Guinness Poetry Award.

The editor offers background information on many of these events. He shows special interest in Jim O’Toole himself, and his play Man Alive that was produced in the Abbey, but it is Betty O’Toole’s story that shines brightest of all.

The idyllic stay at 47 Priory Grove ends with the poet’s return to his childhood country, Inniskeen, at a time when, to his dismay, his old school at Kednamisha was burnt down. A column, reminiscent of his schooldays appears in the Farmers’ Journal, May 25th, 1962, under the title ‘Death of a School’.

[1] The Irish Farmers’ Journal, Jan 6th, 1962, does indeed carry an article: “Good Money in Them Days” a memoir of Kavanagh’s escapades as a wren boy in the 1930s. The editor was Paddy O’Keeffe, who worked for the journal for more than forty years.

Una Agnew is author of The Mystical Imagination of Patrick Kavanagh, Columba Press, 1998 reprinted by Veritas 2019 [a revised edition]. She is joint contributor with her brother Art Agnew to: Love’s Doorway to Life, a triple CD with recitation and commentary on more than fifty pieces of Kavanagh’s work, produced by Éist Studios.