by Sue Leonard

In 1986, the poet Derek Mahon introduced Alannah Hopkin to the writer, Aidan Higgins. The attraction was like a thunderbolt. Leaving his Wicklow home, Higgins moved in with Hopkin, and the two lived together in Kinsale, County Cork, eventually buying a house together.

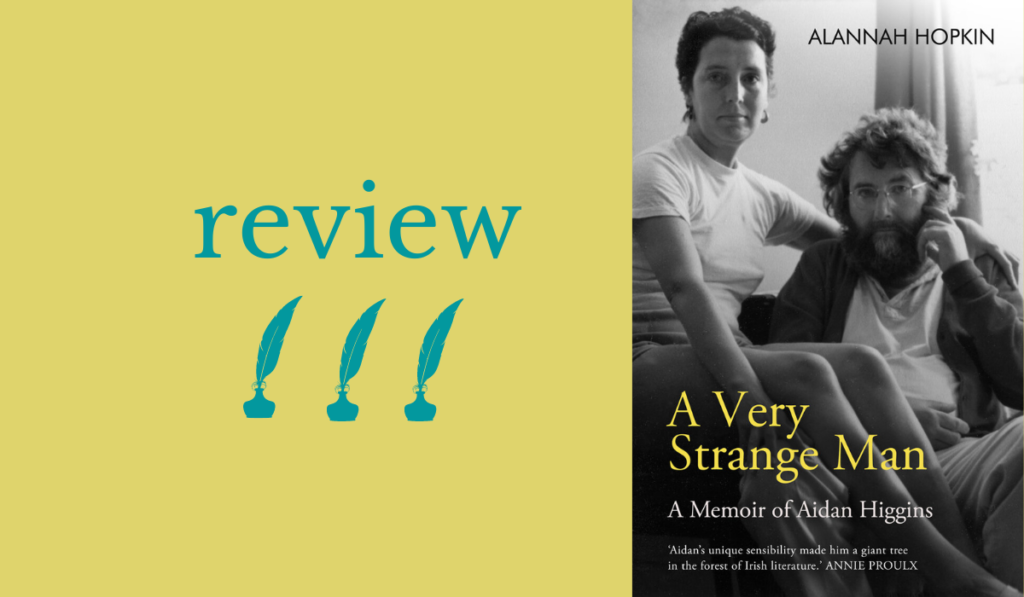

In A Very Strange Man, Hopkin’s memoir of her life with Aidan Higgins, she faithfully records their years together: the good years, the less good, and the downright difficult—and she does so with great insight, humour and wit, and sometimes with quite devastating honesty. Examining his writing, his triumphs and insecurities, juxtaposing those with her own, she takes us through the couple’s social and literary life, writing in delicious detail of their many and varied encounters.

It makes for a gloriously gossipy read, detailing conversations, decors, and intricate details of meals, and of the impressions people made.

Not only did the author have access to Higgins’s diaries, but she also made reference to her own. She credits the writer, Ernest Gébler, the estranged husband of Edna O’Brien for insisting she should record her life. Mentoring her, after her arrival in Kinsale from London, he handed on two pieces of precious advice: to be taken seriously as a writer, she should write everything down, and she should live within her means.

She was managing to do both when she was swept off her feet by Higgins. But as their relationship deepened, living frugally became harder. In order to enjoy a vibrant lifestyle, Hopkin put Higgins’s creativity before her own, sacrificing her fiction writing in favour of writing projects that paid comparatively well.

When they met, Higgins was 59 to Hopkin’s 37. He had already found fame. Best known for his novel, Langrishe, Go Down, filmed with a script written by Harold Pinter, he had been hailed as one of Ireland’s greatest stylists, the natural heir to Joyce, Samuel Beckett and Flann O’Brien. Hopkin had published two novels back in London and was now emmeshed in research for a commissioned work, The Living Legend of St Patrick.

Neither of them had read the other’s work. (The first page of Hopkin’s first novel, A Joke Goes a Long Way in the Country, had the heroine abandoning a Higgin’s book on the floor beside her sofa!). Remedying the deficit, she read through his repertoire, and although she disliked Langrishe Go Down, she admired the bulk of his other work, and was in awe of his stylistic writing.

His analysis of her work was rather less flattering. Starting with her first novel, he declared it, ‘not interesting’.

Although she was able to appreciate his constructive criticism, when a friend told her, sometime later, that Higgins had been reading extracts of her novels to others—people who admired her writing— before rubbishing it, she was profoundly hurt.

For all that, their life together was harmonious. The age difference irrelevant, they suited each other. Both were quiet people, yet social. Both enjoyed outdoor sex. And with their past romantic experience, a marriage apiece, along with many relationships, they both wished to retain a degree of independence.

They fell into an easy rhythm of writing, walking, meeting friends, and coming together for scrabble at six. There were frequent forays to literary readings and events. The honeymoon lasted for eight happy years; then cracks began to appear. Higgins became difficult. Bitter that he wrote books that didn’t sell, he was riddled with insecurity. He wrote to those who gave him bad reviews, haranguing The Irish Times critic, Eileen Battersby for years.

Alannah, herself a highly respected reviewer, writes a great deal about Aidan’s ongoing work, as well as on her own. This, along with her insights into Aidan’s childhood and younger life make for a pleasingly complete picture of the couple, and into a writer’s life in general.

When the couple married in 1999, mainly to regularise legal and financial matters, they were still, essentially, happy together: ‘Aidan made me feel loved, wanted. I believe he felt the same.’

Yet two years later, when Aidan wondered, aloud, if he had married a dull woman, Alannah realised that she had married an unkind man.

This was just the beginning. Aidan became increasingly difficult. He was inconsiderate, boorish, and sometimes rude to his friends, and Alannah bore the brunt of his moods. Had Higgins changed, or was it age and illness making him so crochety?

As Aidan’s physical health deteriorated, so did his mental state. By the time, at 80, he was diagnosed with dementia, Alannah was living with constant pressure, and fear. Having realised she could never leave him, because the real Aidan was somewhere there, buried in the monstrous one, she had to remind herself to show him affection.

‘You are never alone, yet there is no company,’ she wrote. ‘No companionship. Just his self-absorption. Constant monologues, always the voice, talking to himself when I am not in the room, or to the cats who are better listeners than I am.’

When Aidan moved to a care home, Alannah relished the independence that living alone brings. But she was a constant presence at Balintobber Lodge, reading to Aidan, striving, always, to keep the spark of his literary genius alive, right up until he died, in December 2015.

I can’t remember when I’ve read such a moving memoir, or one written with such raw honesty.

Of interest to anyone involved in Ireland’s literary life, it can also be enjoyed as the coming together of two interestingly independent people. It’s also compelling; I couldn’t put it down. It stands out for the clear-eyed view of a wife who doesn’t shy away from sometimes portraying herself in an unfavourable light.

Above all, though, this wonderful memoir is a love story. When they met, Alannah couldn’t have known that life with Aidan would become so difficult. And that, towards the end, she would endure ten years of terror. When someone asked her, had she known the future, would she have got together with him, she said, that, yes, she would never change that.

‘It’s tough all right,’ she said. “But I wouldn’t have it any other way. I had to take a chance, no one could have stopped me.”