Intimate City| Peter Sirr|Gallery Press 2021|€14.50/€22.50|ISBN:9781911338161

In an extract from from Intimate City (Gallery Press), Peter Sirr reflects on bookshops as places for the solitary wanderer, reflections of the inner life.

Shirts for Books by Peter Sirr

I stopped in Clare Street and stared.

Surely? But of course it wasn’t there, Greene’s bookshop had vanished, even if there was still a corner of my brain that expected to see the green painted book barrows under the awning on the street outside the shop as I crossed over from Merrion Square.

Instead, I found myself looking at expensive shirts: the lilac button cuff, the blue Cadogan, the Cavendish light blue stripe. Greene’s was now Henry Jermyn, the London shirtmakers and court tailors, business shirts made from one hundred thread count Egyptian cotton, ties brought from raw silk to finished product in Como, Italy.

Inside, where the books and post office used to be, you could see the neat shelves of business shirts. I found myself reluctant to accept the visible evidence of the new life of this shop. I could still see the bookshop so clearly in my mind’s eye that the shirts kept receding to reveal the slightly chaotic downstairs section, with its small selection of new books and a queue in front of the post-office window and, in September, queues of harassed parents with their long lists of school books. There were no queues today, no fervent shirt buyers scanning the shelves.

The death of a bookshop always hits hard. There are never that many of them to begin with and they are rarely replaced, so that one more opportunity to idle among familiar shelves disappears.

I can’t remember how many hours I spent in Greene’s but I hardly ever passed it without going in. It was not a great bookshop in its last years, but the second-hand section upstairs always demanded to be rummaged through, just in case you missed something the last time or a few new books had come through. Maybe someone had died and their relatives had sold off the library; there might be a clutch of poetry or French novels of the 1930s or a dictionary of agricultural terms or an account of medieval travelogues you had to climb the ladder to pull down.

Regular bookshops push their predictable lines of new titles by the currently favoured, but the real joy is the second-hand shop because, dingy and dull though their stock might often be, their true offering is surprise, the random encounter with a book placed there, you imagine, by some serendipitous god exactly so you should find it.

These are where the unsought, life-changing books are stored, the books you would never have thought to search out.

A book collecting friend was always finding treasures here, which was not always welcome news, but he committed more time to it and was, I suppose, entitled to his rewards. Even bookshops reward productivity. I was more usually than not disappointed but this didn’t matter. The place itself was surprising enough. The massed paperbacks on the walls as you climbed the stairs, those three upper rooms stacked floor to ceiling. One of them was used by staff to parcel up books and send them out to customers.

It all looked very Victorian, the big brown table, the rolls of brown paper, the patient labour.

In that way of second-hand bookshops a large part of the point was atmosphere. What kind of books were they sending out? Who were the customers? Someone somewhere was waiting with interest for a brown parcel secured with twine and Sellotape. Before the internet I don’t think I ever received a parcel of books. It seemed to belong to another era, when one wrote to one’s bookseller with a list of titles and settled up at the end of the month. Now the postman brings me regular jiffy bags with ex Californian library editions of poetry, books from all over the world that I have, often rashly, bought after a bout of browsing when I should have been doing something more profitable.

Greene’s, though, was more than a bookshop. It was a kind of cultural icon or beacon flashing dependably year after year near the end of Clare Street, an unmistakable part of the city.

It had been there, after all, since 1843, and the Pembreys had run the business since 1912 when they first took it over. Now it operates as an online bookseller from an industrial estate on the southern edge of the city, so the business is still intact, dealing mainly in school and library supplies.

Henry Jermyn sells online too, 60% off all shirts and blazers, yet I found myself rooted to the pavement trying to wish all these shirts away and coax back the shelves of dusty books from their sterile suburban storage. I feel a strong urge to go upstairs and have one more rummage. No cheap shirts in a barrow outside entice me in to the new shop. Shirts for books, it doesn’t seem like a fair exchange.

I think briefly of the other bookshops lost to the city. Fred Hanna’s up the road in Nassau Street, the APCK in Suffolk Street, the Eblana in Grafton Street where I used to come as a schoolboy on Saturday mornings to worship at its altar of poetry titles. Parson’s by the canal, of course, but now we enter the era of genuine nostalgia and literary history, ‘where one met as many interesting writers on the floor of the shop as on the shelves’ as Mary Lavin once put it.

Not an entirely public space, there at the centre of bohemian Baggotonia, Seamus Heaney felt: ‘Something told you that this was a slightly privileged zone . . . You were welcome but you were there to behave yourself. And the books for sale gave the same sort of message: they weren’t exactly neutral products, but bore the stamp of Kingly and Flahertish approval.’

There’s a book about it, from which this information is taken, Parsons Bookshop: At the Heart of Bohemian Dublin 1949-1989 by Brendan Lynch. I have only a single memory of it, having marched up Baggot Street and over the canal to inspect it towards the end of the era. I didn’t encounter anyone, but sniffed for the ghosts of Kavanagh and Behan, had a quick scan of the shelves and sloped out self-consciously. The space was too small to hide in. There’s an optimum size for a bookshop, I think, and below a certain square footage browsing starts to feel like intrusion. There’s also, probably, a minimum number of bookshops, and especially second-hand bookshops, for a city, and Dublin has long since slipped below the crisis line.

Where are all the browsers gone? Maybe they are at home trawling through Amazon or Abebooks; or maybe they’ve read enough and have settled down to watch their boxed sets.

The city still has plenty of bookshops but many are part of chains, and most stick to a safely commercial stock. They are retail outlets where the products happen to be books. Or there are antiquarian shops where books are slipped into plastic covers and converted into outlandishly expensive fetish objects.

On the other hand, there is the civilized refuge of Books Upstairs which has journeyed from South King Street (the original ‘upstairs’) to George’s Arcade to College Green and currently resides in D’Olier Street, or the Secret Book and Record Store in Wicklow Street, at the end of a narrow passageway past a doctor’s surgery. Not that long ago the bookshop part took cash, but if you wanted to use a card you had to take your docket to the record shop man at the other end who appeared from his stacks of vinyl to apply the technology. Now we’re getting somewhere, must and old books and half-forgotten music and a complex retail experience. A portal through which you can leave the city and the fixed trajectories of your life.

This is something else which the shirts will never replace. Bookshops are mental spaces, they are places for thinking and dreaming; the best of them have an atmosphere that makes them seem like the outward embodiment of the inner life.

The physical proportions, the disposition of the shelves and the smell of old books all seem like extensions of the imaginative life; they leave an impression that can be entered and re-entered long after you have left. They are part of what Susan Sontag in her introduction to One Way Street calls ‘the geography of pleasure’. She was writing about Walter Benjamin who was a devoted collector of books whose books were also portals into the rooms, in Berlin, Naples, Danzig, Munich, Moscow, where they had been bought. ‘Book-hunting, like the sexual hunt, adds to the geography of pleasure — another reason for strolling about in the world.’

No one will hold a shirt in their hand and fall into a reverie about the shop it was bought in, or will idle away hours in a department store browsing the socks and trousers. A wardrobe is not a library, no matter how well stocked. Bookshops are like parks or museums, spaces where public and private collide, where the inner and outer worlds become porous — to use a Benjamin term — and admit each other. And both are hospitable to the solitary wanderer; they are constructed to serve solitude.

At one point in my life I used to fantasize about running a bookshop, reading books about it, gathering all of the technical information, thinking about stock management and computer systems. All of that was far too real, it was about retail, whereas what I wanted was a kind of private city, or an officially sanctioned privacy. So impractical was the impulse that I’m sure, had anything actually come of it, my wish would have been granted. It would have been a perfect licence for idle reverie. It is, though, one of the reasons I am jealously attached to the freedom of bookshops and why they are the first port of call in any city I visit. And it’s why I am standing outside here now, trying to suck the shirts out of their bubble on Clare Street, lost now to all but the serious buyers of serious shirts.

The only problem is that most good second-hand bookshop dealers know their stock only too well; there may well be surprises, but few enough bargains. The ideal, I thought, as I looked through the window of Henry Jermyn, would be a bookshop operated by a shirtmaker. The shop didn’t last too long, as it turned out. It went into voluntary liquidation in 2017 and is now a plant shop, Howbert & Mays. The god of bookshops is up there somewhere waving a cautionary finger . . .

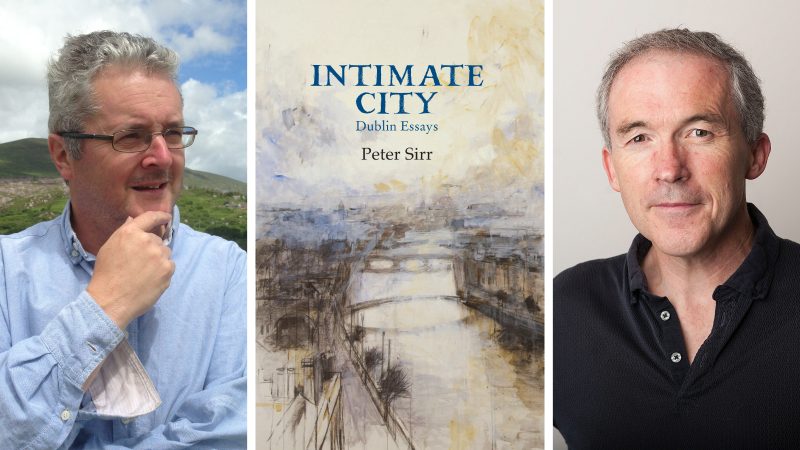

Launch of Peter Sirr’s Intimate City

29 June 2021 | 19.00 | Online

MoLI, in partnership with the Gallery Press, is delighted to host the launch of Peter Sirr’s new collection of essays, Intimate City. Broadcasting from MoLI, Sirr will be in conversation with journalist Frank McNally for the launch of this wonderful new publication.

Reflecting the writer’s long-standing attachment to and obsession with the Dublins of the past and present, Intimate City addresses the contemporary city but also the ancient walled city or the city mapped in 1756 by a French Huguenot or the one enumerated in 1803.