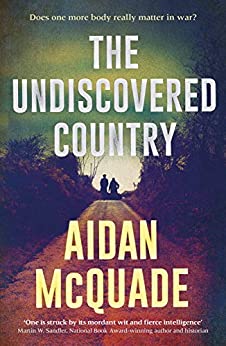

The Undiscovered Country

Aidan McQuade | Unbound | 228pp | €15 pb | 9781783528073

Review by Paula O’Hare

‘It’s not killing and blood sacrifice that makes a nation. It’s taking care of each other and protecting the weak that does that. What we are doing here can help show the world that we can run our own affairs, that due process and the rule of law will be fundamental to who we are and who we wish to become. And that no-one is above the law.’

This is November 1920, the second winter of the War of Independence. The first Dáil is sitting, but now in secret. Ministers are operating from rooms above shops in Dublin. The new State has an army, a parliament, a government and—less visible, more patchily distributed across the country—courts and a police force.

Eamonn Gleason and Michael McAlinden are the Irish Republican Police in Ballykennedy, a small town outside Castlebar. They have no powers and no resources. The court to which they answer consists of a solicitor and a cattle dealer meeting among the conveyancing files. Neither IRP man even wants the job. They are both doing it because they do not fit in to the local IRA. Eamonn enlisted in the British Army in 1914 like John Redmond encouraged him to do, and Mick is a stranger from Armagh, hiding out in Mayo from the Black and Tans. The RIC have been driven from the town, however, so when a young boy is found dead in the river, not drowned but abused and strangled, there is no-one left to investigate the murder unless the IRP do it. The parish court cannot try a murder case but it can return a person for trial, so the policemen are put to work.

Tyre marks show a car came and went from the river at the point on the riverbank where the boy went in. The car owners of the town with access to petrol make a very limited list. They are Jack O’Riordain, the Commandant of the local battalion of the IRA; Peter McLaughlin, the solicitor of the court; Francie Quinn, the cattle dealer, who was on the road doing something for the Commandant; Dick Bruton, the shopkeeper, who is worried he is going to be punished for having been the supplier to the RIC barracks; Doctor Hennessy; and Father Crosby. Everyone on the list, in other words, outranks them, has a reason to lie to them or a professional obligation to keep secrets.

In that impossible situation they are handed two pieces of unusable evidence. The priest straightforwardly tells them who has confessed to the murder. But actually that solves nothing: it is hearsay evidence that might not even be believed. And a child, without realising the significance, tells them who was where when.

A parish court can do nothing with that information. If Eamonn and Mick go to the IRA leadership in Ballina, the person will possibly be left in place because they are effective in their job. Doing anything visible will risk dividing support for the local IRA into two factions and rendering it useless in the war.

If anything is going to be done about the murder, it is going to have to be done extra-judicially and disguised as the work of the Black and Tans.

We are in the same time period and the same moral question as in the film The Wind that Shakes the Barley. In a war, is the imperative to win by any means? Or does that itself devalue what the winning means?

Doctor Hennessy, whose husband had fought and been killed in the Great War, and Eamonn, who had fought and survived, talk this through. If the only imperative is to win, then why not let soldiers shoot surrendered prisoners, to get them used to deliberately killing other humans? How come their soldiers on the right side of a just war still look different and diminished after they have killed a person for the first time?

The author is in a position to ask, having worked in the humanitarian responses to the effects of war in Angola, Ethiopia and Afghanistan, been head of Anti-Slavery International, and having written academically on morality under the pressure of war.

Full disclosure, the reviewer has known the author since he was born and was always going to want to give this book a glowing review but, fortunately, Aidan, it turns out that it merits it.

The book uses as a framing device the idea that its source is the Bureau of Military History. If any reader doesn’t know that this is a real resource of first-person accounts of the Easter Rising, the War of Independence and the Civil War—it is, and it is fascinating in its own right.

Highly recommended.

***

Paula O’Hare is a public sector lawyer who likes detective novels.