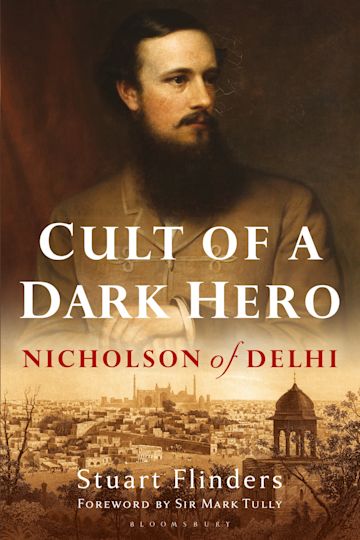

Cult of a dark hero: Nicholson of Delhi|Stuart Flinders|Bloomsbury Academic|£12

“Flinders’ biography is a well-researched, fully referenced, accurate and balanced life of a very peculiar and controversial Irishman.”

by Donal P. McCracken

My father was instrumental in bringing the statue of John Lawrence from Lahore to Derry, where it now stands in front of Foyle College, the old school of India’s first viceroy.

About the same time, and thanks to the intervention of Lord Mountbatten, the statue of General John Nicholson, another giant of the Great Rebellion or Indian Mutiny, was brought from Delhi to Dungannon Royal, Nicholson’s old school.

Statues, of course, have become contested ground nowadays and another statue of Nicholson, in Lisburn, has drawn attention from the iconoclasts.

The chances of its survival in a street setting are slim. Ironically, Nicholson would have cared little about any such removal, as indeed he would have dismissed its erection in 1921.

He never had any illusions about his popularity, or lack of it. He was a loner, as disliked when he lived by many of his fellow white officers in India (apart from the small coterie of thinking officers who clustered around the liberal-minded Henry Lawrence) as much as he was respected by his Indian troops.

Lives of Nicholson

I must declare an interest in this book, having had a life of Nicholson published the same year as Stuart Flinders’ volume.

In the 165 years since Nicholson died, there have been a handful of lives or part lives published, some of them under various guises.

These include Captain Trotter’s The life of John Nicholson (1897), Hasketh Pearson’s pre-World War II call to arms, The hero of Delhi (1939), Flinders’ The cult of a dark hero (2018) and my own Nicholson (2018).

Hero turned villain

Two children’s books on the imperial hero are J. Claverdon Wood’s ripping yarn When Nicholson kept the border (1925) and Ernest Gray’s Nikkal Seyn (1947).

Then there are books which touch closely on or have important chapters on this ‘hero turned villain’: John Kaye’s Lives of Indian officers (1867); R.G. Wilberforce’s dubious An unrecorded chapter of the Indian Mutiny (1894); Lord Robert’s famous Forty-one years in India(1897); I. Giberne Sieveking’s A turning point in the Indian Mutiny (1910); and more recently Charles Allen’s pioneering Soldier Sahibs (2000) and Michael Silvestri’s Ireland and India (2009).

Of the early lives, Trotter is by far the best, written by a soldier about a soldier.

Peculiar and controversial figure

Flinders’ biography is a well-researched, fully referenced, accurate and balanced life of a very peculiar and controversial Irishman.

It follows a chronological journey through Nicholson’s 34-year-long life, from his difficult Irish childhood (his father, a Dublin doctor, dying when he was 10, and his overtly religious mother reduced to genteel poverty) and being sent to India as a boy soldier aged 16.

The book tracks Nicholson though his adventures as a POW in Afghanistan; then the Anglo-Silk Wars; as an administrator in the restless frontier (and much later Taliban) region of Bannu; and finally, during the Great Rebellion of 1857, when Nicholson led a military flying column which effectively subjugated the Punjab and as such was a major reason for the British holding on to their Indian possessions.

The climax of this book is the dramatic story of Nicholson leading his troops over the great walls of Delhi, being mortally wounded in the hour of victory. As an adventure narrative, this is a good read.

Nicholson’s Irishness

There are a few matters of emphasis, rather than anything else, on which I would tend to diverge or add. The nature of Nicholson’s Irishness is one.

Nicholson was a product of the evangelical revival in the Church of Ireland in the early nineteenth century and considered himself as Irish, speaking with an ascendancy accent.

He tends to be portrayed in this biography more as an Ulsterman. I must confess, I started working on Nicholson thinking of him as that, but ended up concluding he was essentially Anglo-Irish.

He was born in Dublin and received an early education while living in Delgany, before the widowed mother took her family north to her old home in Lisburn. Nicholson, unlike the mother, was certainly no northern Bible basher.

Violence

The violence associated with Nicholson could do with more analytical discussion.

Many of the stories relating to this are at best hearsay and need taking with a large pinch of pink Punjabi salt.

Nicholson certainly had a temper (fueled by a potent cocktail of medicines he took) and he was not slow to have people flogged when he thought it necessary.

But many of the Nicholson stories are later inventions or exaggerations from when the jingoes got hold of his memory and turned him into a muscular champion of empire. In particular Wilberforce’s An unrecorded chapter of the Indian Mutiny (1894) should be treated with caution.

This book includes the legendary tale of Nicholson hanging the camp cooks who were about to poison the entire military column. In fact, Nicholson was in Delhi when that was supposed to have happened.

Nicholson’s violence was essentially the institutional, fighting violence of the frontier soldier.

There were no mess room brawls (he tended to sit quietly by himself when eating his food); no duels; no fisticuffs behind the barracks and certainly no flayings. Moreover, Nicholson’s occasional private rants to his few friends and his mother cannot be taken as actual violence. This is not to excuse, but it is to explain.

Unfounded accusations

Similarly, the accusation often-levelled against Nicholson that he hated India and Indians does not hold water and is largely based on a throwaway comment when he was under profound psychological stress having just been badly treated as a POW in Afghanistan and having recently found the dead and mutilated body of his younger brother in the Khyber Pass.

In fact, Nicholson was more at home in the company of Indians than most of his fellow whites. And the one time he did take home leave in Britain and Ireland, he returned to India early and away from his mother pressing him to find a wife.

On the suggestion that Nicholson was gay, Flinders quite correctly comments that there is no evidence for this.

The destruction of some of Nicholson’s letters after his death by his mother was most likely on the grounds of ecclesiastical comments rather than sexual confessions. Nicholson was wobbly on established religion, something which perplexed and distressed his great friend Colonel Herbert Edwardes.

Popularity

The theme of Nicholson’s unpopularity during his lifetime could perhaps receive more attention.

Much is explained by the fact that Nicholson was inherently shy and gauche, creating enemies among white officers who were consequently ever-keen to badmouth him, especially as he was part of the Henry Lawrence protected inner circle.

Conversely, Nicholson’s popularity is equally complex.

In the past, too much has been make of the small cult – the nikolseini – who worshipped Nicholson. He was embarrassed by them and indeed tried to persuade them to transfer their adoration to a colleague.

His relationship with the Indian troops in his flying column was something different. Nicholson’s relationship with his body guard and loyal follower Hayat Khat is well covered in the book.

Apart from the fact that Nicholson was successful and independent minded in what he did, the animosity between him and his fellow white officers was in part because he had a remarkable capacity to judge character and, completely lacking in any tact, was not slow to denounce incompetency.

But here was another factor. Nicholson was, and again ironically, awkward in his dealings with those he did not know and trust. This made him come across as cold and aloof.

The Great Rebellion

The Great Rebellion was not only a military revolt but also a civil war, and had all the hallmarks and bitterness of the latter; it was a brutal affair.

Martial law plus local military decrees basically gave carte blanche for British reprisals.

Most of these occurred after Nicholson’s death, however, there is no question that Nicholson had sepoys captured straight off the battlefield summarily shot – “The punishment for mutiny is death”.

However, Flinders is correct in saying not all prisoners were executed. He is also correct in describing Nicholson’s activities as ‘rough justice’. What is not always said by modern writers is that the insurgents were no less brutal in their dealings with British prisoners.

A young man’s story

The military aspects of Nicholson’s life are well told in the book, especially the dramatic saga of the assault led by Nicholson over the walls of Delhi.

To date, no one has questioned Nicholson’s ability as a good if not a brilliant soldier, fearless, tenacious and focused. Nicholson’s is a young man’s story. Had he lived and matured with age, his biographers would have sung a very different song.

When I submitted my manuscript, my publisher advised that I cut the last chapter relating to Nicholson’s legacy and memory. I think he was correct, for this after-life is a different ball game.

Flinders bravely adds a concluding chapter. It was a generation after his death that Nicholson was resurrected by the jingoes as an imperial hero.

I may say that one will look in vain in Nicholson’s letters for anything which might be termed a rah rah for empire. But it was inevitable then that the anti-imperial writers of recent years should single Nicholson out for opprobrium.

It is to Flinders’ credit that he seeks to take a more balanced middle ground, neither brow-beating nor pandering to modern moral rectitude. So, at the end of the day, the reader must pass their own judgment on this extraordinary and fascinating Irishman.

Prof. Donal P. McCracken’s Nicholson: How an Angry Irishman became the Hero of Delhi is published by The History Press. His latest work, You will Dye at Midnight: Threatening Letters in Victorian Ireland is published by Eastwood Books.