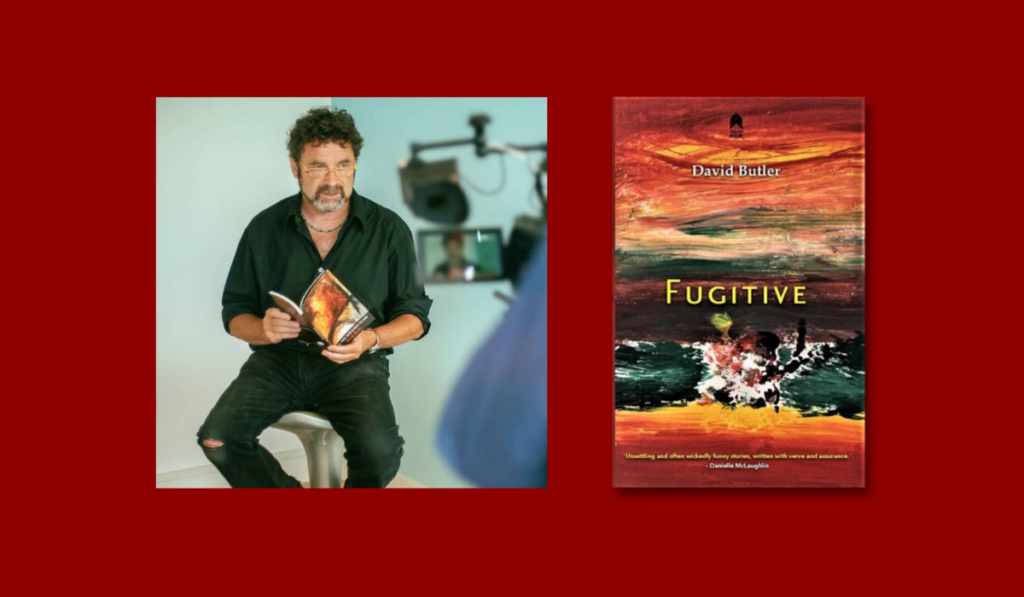

As the restrictions finally begin to lift, a disturbing story from the uncertain days of the first lockdown, from David Butler’s new collection, Fugitive (Arlen House).

Distancing

As the call went on, the knot in Emily’s gut tightened.

She couldn’t take the chance that Betty Beglin might simply hang up, smiling bemusedly (as Emily supposed), not knowing there was a deathly-serious purpose to the call. She couldn’t take the chance he might come back, early.

But of all things, Emily hated confrontation. Interaction of any kind made her apprehensive. Sometimes, approaching a hairdressers or a shoe shop in the days when one could still do such things, she’d actually caught herself practicing in a low voice what she was going to ask for, as though she were back on her year abroad in France.

A knock at the door or a ringing phone, and dread would turn a sudden somersault. Why could people not just text?

Betty Beglin could talk for Ireland. Her chatter had already dragged on so long Emily’s latte was cold. Coffee had been a mistake. Her fingers, caffeine-quickened, were all a-jitter even as she’d dialled, so that it had taken two goes before she’d got the number right. But now that Betty had stopped banging on about whatever it was she’d been banging on about while Emily’s innards were squirming like eels approaching a saucepan, the lengthening silence was ten times worse.

And at any moment, Frankie really might return.

She looked out over Crossthwaite Park. No sign of him. No Joxer straining at the leash. She swallowed a dry dribble of saliva. ‘I meant to ask,’ she tried to compose her features to approximate facetiousness, ‘how’s that new au pair working out?’

‘Toni? She’s fab! The girls are crazy for her.’

Toni. Antônia. That was it! ‘Yeah?’ Her heart fluttered skyward, a lark startled from long grass. ‘She’s very young, no?’

‘The company said she was eighteen. Yeah. I’m pretty sure, eighteen. Gi-nor-mous family back in São Paulo, eight or nine I think she told us, so she’s well used to having bundles of youngsters pulling out of her the whole time. A cambada, she calls them.

‘She’s a scream, a real live-wire. But honestly, she’s been marvellous. I mean Shona I can understand. Shona takes to everyone. But Pauline? For the longest time they thought Pauline was,’ her voice dropped to a confidential whisper, as though there might be an eavesdropper, ‘(On. The. Spectrum.) Can you imagine! Pauline? She’s shy, that’s all. Shy! You know? I don’t see why a child isn’t allowed to be shy these days.

‘But ever since Toni Oliveira arrived, she’s a different kid. Right from the get-go, she took to her. Of course it helped that Shona took to her, first. She often takes her lead from Shona. You see her English isn’t great, I mean Toni’s, but then I suppose that’s what has her over here, to improve. I mean she’s forever saying things like, ‘I didn’t went’. You see? ‘I didn’t went.’ It’s kinda cute, really. And Shona thinks it’s hilarious, but instead of getting annoyed about it, Toni sorta plays along. Makes a game of it. And then Pauline joins in, all giggles. I mean it’s lovely to see her, giggling away and spanking poor Antônia’s behind. But really, she’s marvellous. I can’t praise her highly enough. And George! George is mad about her…’

Had she stopped for breath once in all that paean, while Emily’s breath had been shallow and rapid and ineffective?

George is mad about her. Well that about said it all. ‘But she must miss her home, no? Especially now, with all this…’

‘Oh God! Bra-zil!?? You should just hear her on the subject of that bobo they have for a President over there. Bobo. That’s what she calls him. I can’t think of his name but she says he’s like a Latino version of Trump. Get this! But without Trump’s class! Ha! Ha!’

Emily took a breath. She took a slow, deep breath. She held it in till it hurt. Then she exhaled, entirely. Ok. Calmness. ‘But wouldn’t she have to be studying over here, isn’t that the deal? Doesn’t their visa depend on them studying here, too?’

‘But that’s just it! The language school has been marvellous. They run these online classes. Zoom, the same thing George is using for his conference calls. Look, Emily, I better leave you go. I have about a zillion things to be doing this morning…’

Now or never. Say it! Say it, for Christ’s sake. ‘Betty. Look. Can I ask you something?’ Heartbeat. Heartbeat. ‘A… favour?’

‘Sure. Ya! What is it?’

‘She, ahm.’ Say it! ‘She’s walking around…,’ say it, dammit! ‘…in these short little pants and, and a singlet. And no bra, like it was… And with her belly on show for everyone to admire…’

An unimpressed pause. A shift in the barometer. ‘That’s the Brazilians, Emily. They’re like that. Every one I’ve met, anyway. They’re young, God’s sake! And the way the weather’s been, well! Hasn’t it been just mar-vellous? The Dublin Riviera, George calls it…’

Knee–length boots? In a heatwave you don’t wear knee-length boots! Not when you’re eighteen. Now that she was stepping off the precipice, Emily’s voice hardened. ‘Then can you ask…Antônia…not to be hanging around Crossthwaite Park every evening? Couldn’t she use, I dunno, the People’s Park, or somewhere? It’d be a lot nearer to your place, for starters.’

A hostile static met Emily’s request. Betty Beglin was just the type to take this for a social snub, whereas that was the last thing on Emily’s mind. ‘I mean it’s ridiculous. It’s not like any of them are social distancing. They’re hanging around together like they were at Electric Picnic, or something…’

‘What’s this about? What exactly has got up your nose, Emily? Toni has no more harm in her than any Irish girl her age.’

Now Emily was fired up. Annoyed.

True, she was annoyed at her own lack of composure, her own lack of sleep in recent days as images and arguments tumbled like laundry through her mind throughout the small hours.

But at least she was able to channel it now. Heart pounding, she took up the gauntlet. ‘Well, she clearly doesn’t know the first thing about social distancing. Yesterday evening, when Frankie was out walking Joxer, she stood there in her hot-pants not two feet in front of him, never mind two meters. Flashing her teeth up at him. Big, bubbly laugh out of her, I could hear it though we’re at the other side of the park. I even saw her squeeze Frankie’s bicep.’

A stony silence. She could all but hear Betty Beglin’s smile freeze to a Botox rictus. ‘Emily. Can I suggest, if you’ve a problem with Frankie talking to Toni, then perhaps you should take it up with Frankie, no?’

A heart murmur. A trapped bird. ‘Betty,’ her voice, scarcely there. ‘Could you not just ask her?’ Because she couldn’t say it to Frankie. She daren’t. ‘Please?’ Not after what happened last time she’d reproached him for his free-and-easy manner. Not now, when he was fearing for his job, and tramped round the house all day like a caged animal.

‘Emily. Ok. Listen to me.’ Her tone had altered again. Another barometer-shift. To something like concern. ‘Has he…?’ Because Betty had seen. Last year. After he’d…

‘Emily, if Frank has said or, or… done anything to you, you have to report…’ But Emily wasn’t listening. The hall-door had swung shut, shuddering the hall and bannisters. The thud resounded like a gunshot through her chest cavity.

As Joxer’s nails spilled like a hundred ball-bearings across the parquet floor, as he blundered upward toward the mezzanine, Emily plunged the phone deep into her pocket.

She clamped her eyes shut, inhaled, composed the smile to meet their return; the smile that, ever since the lockdown started, seemed only to put Frankie on edge.

David Butler is a novelist, short story writer, playwright and poet. He is the author of City of Dis (New Island), All the Barbaric Glass (Doire Press), and Liffey Sequence (Doire Press). His new collection Fugitive is out now with Arlen House.