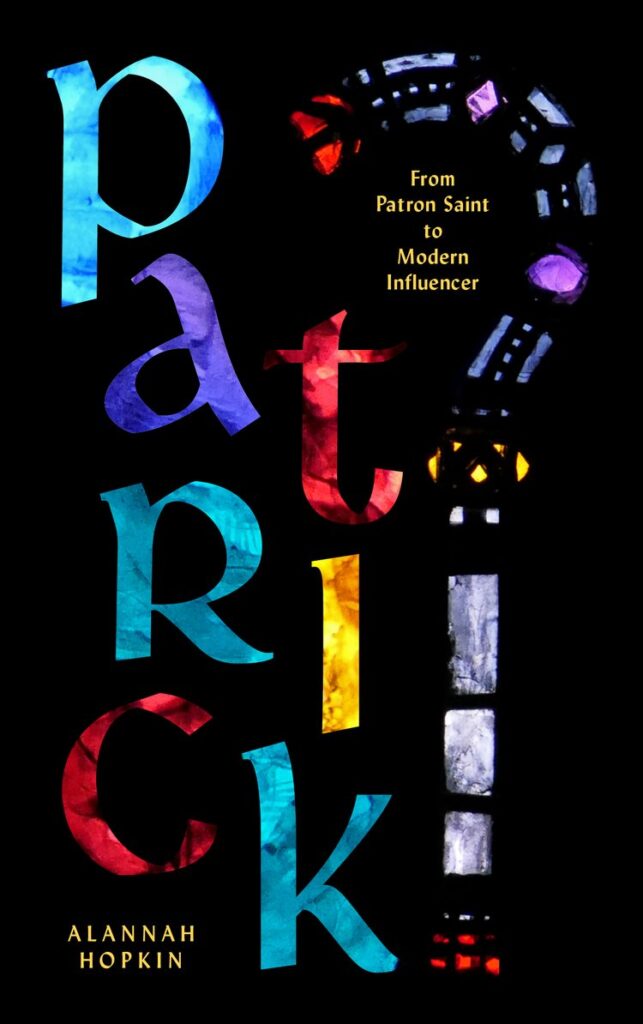

From drowning the shamrock to the first parade—read about St Patrick’s Day in 18th century America in an extract from Patrick, by Alannah Hopkin (New Island)

by Alannah Hopkin

While figures for emigration from Ireland were high for the whole of the nineteenth century, they reached their peak in the years before and after the Great Famine of 1845.

Significantly for the spread of the cult of St Patrick, those who left during these years came, by and large, from the same social class which was instrumental in elevating St Patrick and the shamrock to the status of national symbols – the rural poor.

It was the picture of St Patrick as national hero, a grey-bearded man in green bishop’s robes with the expelled serpents writhing at his feet and a border of shamrocks, whose anniversary must be given a boisterous and showy celebration on 17 March, that these emigrants took with them across the sea.

Between 1801 and 1921 over eight million men, women and children left Ireland, a figure which is equivalent to the entire population of Ireland at its peak, just before the Great Famine.

Well over two-thirds of the emigrants headed for the United States, where the majority of them settled in the great ‘Irish’ cities of New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Chicago.

Prosperous Ulster Protestants

These nineteenth-century emigrants who carried their nationalist sentiments and their devotion to St. Patrick across the Atlantic were not, however, the first Irish people to move to the New World.

From the early eighteenth century there had been a steady movement across the Atlantic of a rather different kind of person. While the vast majority of nineteenth-century immigrants were impoverished Catholics from rural districts seeking employment as servants and labourers, eighteenth-century immigrants in America were mainly relatively prosperous Ulster Protestants – farmers or merchants – who wished to contribute their skills to the colonisation of the New World.

They were also, in some cases, seeking an atmosphere which would be more tolerant of their Protestantism than Ulster. Before the American War of Independence, Catholics were not welcome in the Crown Colonies, unless they happened to be very wealthy.

So it is a rather ironic fact of history, given that St Patrick is so closely associated with Catholic America these days, that the first recorded festivities and Friendly Societies associated with the saint in the New World were founded by Protestants; in some cases Catholics were specifically barred from participation.

The first recorded meeting of Irishmen on American soil in honour of St. Patrick took place in Boston on 17 March 1737. Presumably there were informal celebrations among private individuals before that date, but as yet no record of them has emerged.

Charitable Irish Society

The 1737 meeting has come down to us in history because the gentlemen assembled on that occasion formed themselves into the Charitable Irish Society, whose aim was to provide assistance for their fellow countrymen in those parts who were in economic difficulties.

Their Rules and Orders at that date stipulated: ‘… the managers to be natives of Ireland or natives of any other part of the British dominion of Irish extraction, being Protestants and inhabitants of Boston.’

However, the bar on Catholic membership of the Charitable Irish Society was either quickly repealed, or simply ignored, as Catholic gentlemen were to be found in the Society by 1742.

The fact that 17 March was chosen for the founding of the Charitable Irish Society indicated that the Irish immigrants in America, even at this early date, observed the feast of their patron saint.

The drowning of the shamrock

Not all the Irish in America at this time, however, were immigrants. During the lean years of the eighteenth century and the enforcement of the Penal Laws, many Irishmen chose to seek a military career abroad.

Some joined the Catholic armies of France, Austria and Spain. Others found themselves in the English army, and a significant number of Irish, both officers and men, were subsequently posted to the colonies.

They were to play an important part in establishing the American tradition of St Patrick’s Day celebrations.

The earliest mention of military observance of St. Patrick’s Day in America – 17 March 1757 – does not, however, feature a parade. Instead it is the other aspect of secular Patrician festivities that is mentioned: the drowning of the shamrock.

It was the custom for the English army to issue an extra ration of grog on 17 March, in which to ‘drown the shamrock’.

In 1757, during the Seven Years War, the English troops were camped at Fort Henry, forty miles from the French stronghold of Ticonderoga. The English garrison consisted largely of Irishmen – so, by an odd twist of history, did the French contingent.

The English troops, provincial rangers under John Stark, were issued with their extra rations of grog for shamrock-drowning on 16 March, as they were wary of a French attack on the next day. The French did indeed attack on 17 March, the Irish among them hoping that the Irish among the English would be taken unaware in a ‘groggy’ state. John Stark’s precaution ensured that his troops were fully alert on 17 March, and the French attack was repulsed.

The first parade

The first St. Patrick’s Day parade on record was held in New York in 1762, and seems to have been a spontaneous event arising from the high spirits of a group of militia men.

They were on their way to a St. Patrick’s Day breakfast at a tavern on Lower Broadway in New York City, and decided to march there behind their band with their regimental banners on display. The sight delighted participants and spectators in equal measure, and marching on 17 March to the rhythm of bands playing Irish tunes became a part of the American way of life.

There are records of celebrations on 17 March throughout the 1770s and 1780s in New York and Boston, mostly taking the form of breakfasts and balls hosted by Friendly Societies, and military marches. Many of the Irish Friendly Societies suspended their meetings between 1775 and 1784 on account of the War of Independence.

Many others were founded immediately after independence, for example the Society of the Friendly Sons of St Patrick, which was formed in New York in 1784.

They described themselves as ‘a benevolent and patriotic society of Irishmen and their descendants of every shade of political and religious belief’, which was founded ‘to assist unfortunate and distressed natives of Ireland in the city of New York.’

Little did they know just how many of these were to appear over the next 100 years.

The immigrants of the famine years were exiles not for a better way of life (as were those who came before and after them), but simply for survival. Their longing for home turned into a virtual cult of homesickness.

It is no great wonder, then, that those generations of Irish immigrants who lacked a background of family elders and did not, owing to their youth and minimal education, have a great deal of knowledge about the country that they had left, seized upon the one thing that they all remembered from home – St Patrick’s Day – as the occasion on which, literally, to parade their Irishness, and join together in celebrating their difference from their neighbours.