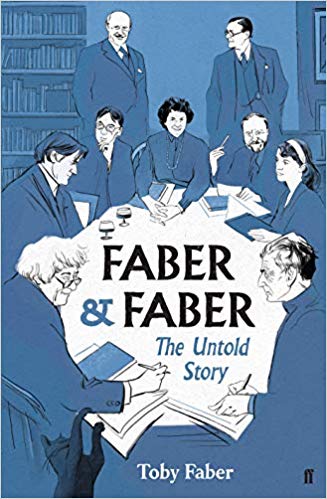

Faber & Faber: The Untold Story: The Untold Story of a Great Publishing House. Faber & Faber; HB; 440; 9780571339044.

Review by Mary McCarthy

Faber & Faber has remained independent for 90 years, and its story, compiled by the grandson of the founder Geoffrey Faber, is as much a celebration of a well-written letter. While Toby Faber gives an introduction to each chapter, outlining the context of what was going on in the company and the wider world, the story is mainly told through written letters, diary entries, catalogues, board meetings and memoranda. He also offers discreet explanatory notes between letters, though mostly the replies offer all the narrative needed.

It is a hugely interesting read—you marvel at the maleness of the industry, when now publishing is predominantly female, and who knew that publishers had a boom time during the war years? It is a joy to read—not surprising, considering the talent behind many of the letter writers: Ted Hughes, Philip Larkin, Seamus Heaney and Lawrence Durrell, to name a few.

An important thread is the relationship between Geoffrey Faber and the poet T.S. Eliot, who joined as a director in 1925, tasked with bringing in literary talent when the company was a scientific printing press controlled by the Gwyer family. In 1929 Geoffrey bought out the Gwyers and Faber & Faber was born and, after disposing of its nursing titles, went full on towards glittering literary success.

In his introduction, Toby Faber repeats the well-known joke that nobody goes into publishing to make a large fortune, but rather to make a large one smaller, and it is true that money worries were often in the background.

Irish connection

Later, a key player in keeping the firm afloat was Ulsterman Charles Monteith, who joined as a director in 1954. Monteith’s great ability was to juggle a dedication to literature with the need to make money and he quickly established his own list of young writers (many of them Irish) who were later to become very successful. These included P.D. James, Philip Larkin, Samuel Beckett, Seamus Heaney, John McGahern and Richard Murphy.

Monteith played a big role in the years following Eliot’s death and was a close colleague of the poet for a decade, leaning heavily on him for advice and confirmation of his opinions. He had good taste, plenty of flair and lots of good luck. After taking Lord of the Flies off the slush pile to read on a train ride, he ignored the comments another reader had left about it being useless and immediately spotted its brilliance. He was the one to note the potential in Beckett in 1956 with Waiting for Godot, John Osborne in 1957 with Look Back in Anger and wrote back to Seamus Heaney in January 1965 after reading some of his work to say how much his poems had interested him. ‘Several people here, including myself, read them and were very impressed with them. Over-all feeling is that the collection is not quite strong enough for publication, but that it does show definite promise,’ he wrote.

Interviewed later in life, Seamus Heaney said of receiving this letter, ‘I just couldn’t believe it, it was like getting a letter from God the Father.’ Seamus wrote back in May of that year, ‘I enclose a few poems for your consideration. You have already seen a few of these in the batch which you obtained in December. I hope this group is a bit stronger.’ And stronger it proved to be, leading to the publication of Death of a Naturalist in 1966—Seamus Heaney’s first major published volume.

James Joyce was another Faber author, publishing Finnegans Wake in 1945, though declining to publish Ulyssesowing to fear of prosecution (Allen Lane published it). Geoffrey Faber took instantly to Joyce, writing in June 1931 after meeting him for the first time: ‘Joyce, a little tired-looking man, wearing glasses, evidently physically under the weather, talking little and quietly, perfect manners. One couldn’t but like him, and feel his quality.’

Comfort for writers

This book will be a source of comfort for any writer. It shows the painstakingly slow trajectory of getting published—the often initial rejection and eventual success following dedicated reworking will be music to any writer’s ears. It also offers a glimpse into the frequent second-guessing, like the self-doubt shown in the letter written by Hanif Kureishi to his publisher in 1986 before Faber went on to publish My Beautiful Laundrette in 1984:

‘The thing I really want to do—write a novel—is no nearer starting. In fact when I think about it I get physical symptoms; acute anxiety and general fuckedupness. I have so much doubt about my own talent, which is usual in writers, but I find it terribly debilitating.’

The second half of the 1980s was a golden time for Faber with two Booker winners in a row (Oscar and Lucinda in 1986 and Remains of the Day in 1987). There was plenty of luck, with the money received from Cats keeping insolvency at bay more than once (the musical was based on T.S. Eliot’s Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats).

Publishing a book used to take a lot of time and this slow-and-steady approach was less commercial than it is today. Faber took in authors they felt showed promise early in their careers, harnessing their talent over many years, with the full acceptance that some would possibly never be accepted by the readers. This formula produced some work that appealed to a few but much more that appealed to many and maintained lasting importance. The spoof letters written by T.S. Eliot are reason alone to read this entertaining account and intriguing history of modern publishing.

Mary McCarthy

Mary McCarthy is a freelance journalist writing for a number of publications. She is an avid reader and an iron-willed book club administrator. @maryknowsbees