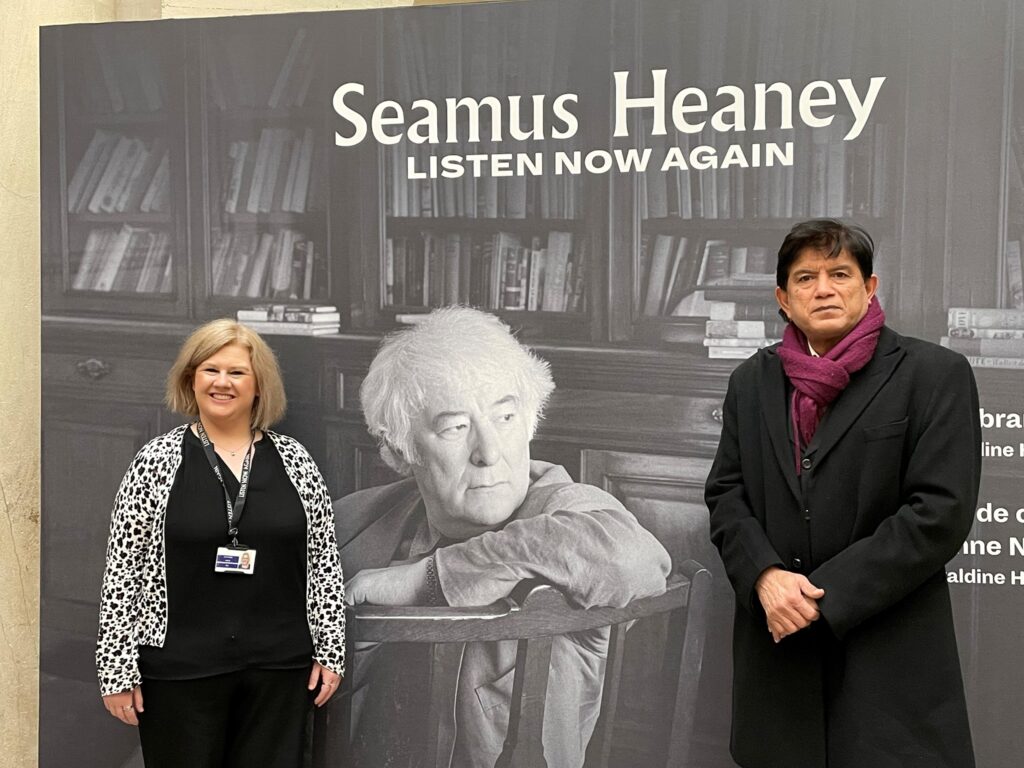

Ruth McKee visits the Seamus Heaney exhibition Listen Now Again, and talks with Ann-Marie Smith from The National Library of Ireland about a moving, multi-sensory experience

Listen Now Again

by Ruth McKee

“We should offer tissues as part of the experience.” Ann-Marie Smith laughs, telling me she sees quite a few people going in one way to Listen Now Again, and coming out quite another.

It’s a multi-sensory exhibition which draws from the well of material the National Library has from Seamus Heaney‘s life—diary entries, notebooks, postcards, personal belongings (including his writing desk). With video, audio, and photography—both large scale images and intimate family moments—walking through it is a bit of an emotional car-wash.

I apologise to Ann-Marie as we go upstairs, having just exited the exhibition with something in my eye—although of course a few tears aren’t anything to be sorry about. “We can blame it on Covid,” she says, joking, and after a few minutes it feels like we’ve known each other for ages rather than having just met.

Ann-Marie is one of those people who look like they are exactly the right person to be doing precisely what they are doing; she is the Exhibition Manager of Listen Now Again, and talks with passion and effervescence about her work, The National Library, and of course Seamus Heaney.

She tells me about the poet driving all the boxes of archive material up to the Library himself, about his kindness, humility, and humour, and about the support of his wife Marie and family, who were the first to experience Listen Now Again.

We’re upstairs in the The Cultural and Heritage Centre at Bank of Ireland, College Green, opposite Trinity College.

Its grand, external structure is no less compelling inside, with a foyer that lifts your eyes to the architecturally beautiful window in the domed ceiling—fitting, since architecture and visual art are important in Heaney’s work, something which is explored in talks hosted by The Glucksman, in University College Cork today.

Voice

“the language could give you a kind of aural gooseflesh…”

Seamus Heaney, Feeling into Words

We sit down and our voices echo; we’re sitting distanced in a room that would ordinarily be used for students, for classes and workshops, crammed full of bodies, breath and life. Now, that’s unthinkable. But Ann-Marie says that restrictions haven’t meant fewer people having a chance to see the exhibition.

Thousands of students from all over the country have been able to experience Listen Now Again from their laptops and schools, and she points out that for a school in Mayo, Covid or no Covid, a school trip all the way to Dublin would be out of the question.

From 2020 onwards virtual tours and workshops opened up Heaney’s words and pictures to many more people than would have been the case otherwise.

We talk then of the exhibition itself, although exhibition is a word that doesn’t feel right to describe something that feels like stepping into a life.

I tell her that it’s hearing his voice that has me a little emotional and she agrees; she’s probably heard this a thousand times before but isn’t letting on.

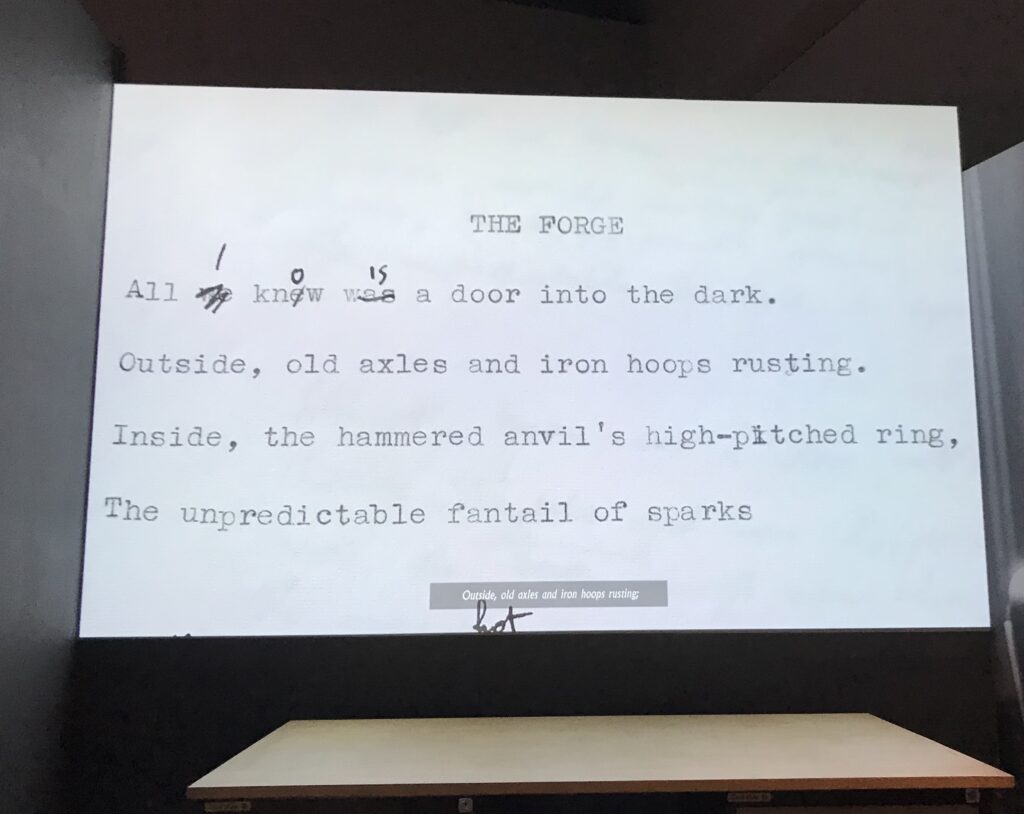

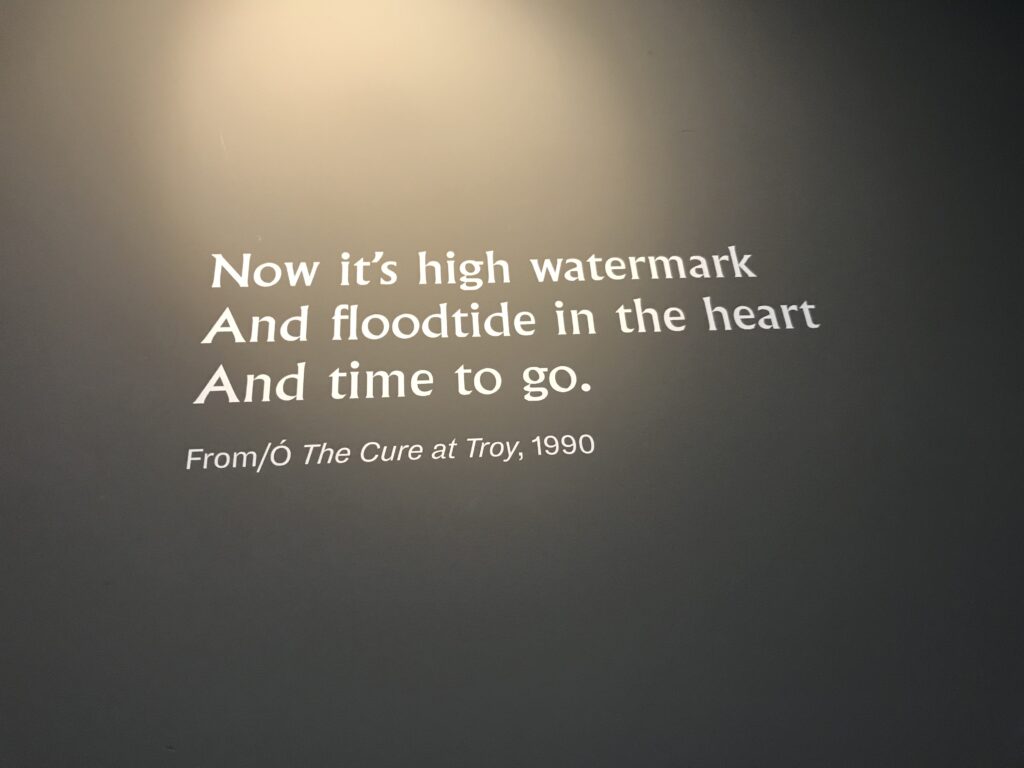

Your senses all switch on when you walk into Listen Now Again. Here you are with your heart off guard and here is Heaney reading The Forge to you as you sit on a bench and watch the words appear, his own type-written draft with its crossing outs and adding ins, the anvil on the metal.

The earth of his accent reminds me of fatherly sounds, comforting, exhorting, didactic, wise.

“Finding a voice means that you can get your own feeling into your own words and that your words have the feel of you about them; and I believe that it may not even be a metaphor, for a poetic voice is probably very intimately connected with the poet’s natural voice, the voice that he hears as the ideal speaker of the lines he is making up.”

—Seamus Heaney, Feeling into Words

Ann-Marie tells me it’s often the way; it’s the voice of the man that is an intravenous line. People are invigorated.

She tells me about a woman that comes in most days at the same time, just to have somewhere quiet and peaceful to be; about scholars who come on pilgrimages; about tourists who’ve heard the name in politicians’ mouths or know Heaney’s face from a poster of famous Irish writers and nothing more; about people who have never heard of him, who’ve never read any poetry at all but escape from the busy footfall of Westmoreland Street to have their eyes opened to something.

It can be a safe place for some she says, a place of learning for others, and a haven for a few.

Different sides

It depends what you’re looking for, Ann-Marie explains as I tell her I glanced at the wall of newspaper front pages about the atrocities during The Troubles and moved swiftly on; something that was the backdrop to my childhood isn’t something I want to dwell on.

But this is what draws many people in, she says, how Heaney wrote with insight about something so brutal and complex, willing also to speak truth to power.

Drafts

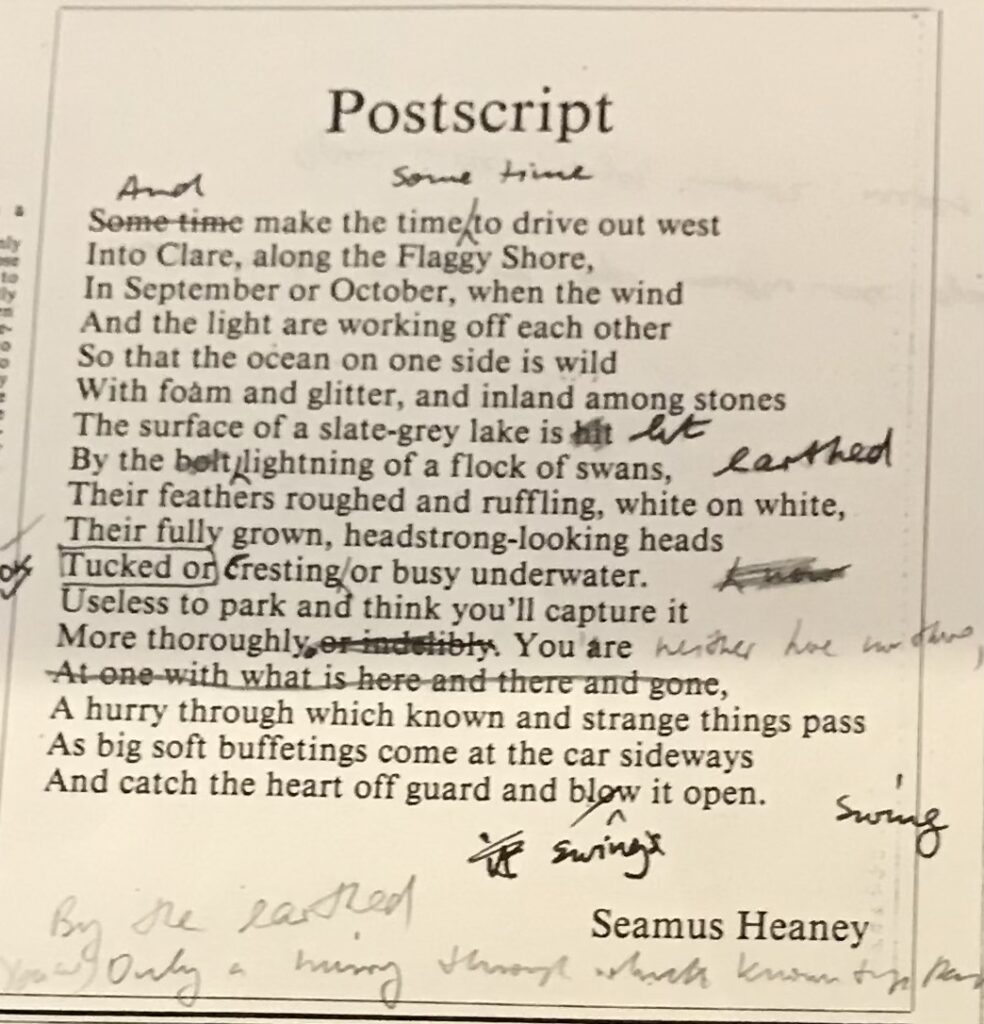

The exhibition is full of early drafts, of letters from publishers and to peers, a kind of beautiful bureaucracy of the writing life.

Postscript is beloved of many, and I was wondering what it would be like to see all Heaney’s notes in the margins, the messy work that goes on behind a tapestry, if it would ruin the magic.

The short answer is no. If anything it makes the poem more of a living thing. You can see all the marks and corrections, lines pulled this way and that until there is that simple but devastating music Heaney’s poetry has.

Each time you read it, it’s like driving over a big rise in the road, with that drop somewhere in your abdomen at the last line, the little shiver—or wherever it is in the body where words affect us.

The Small Things

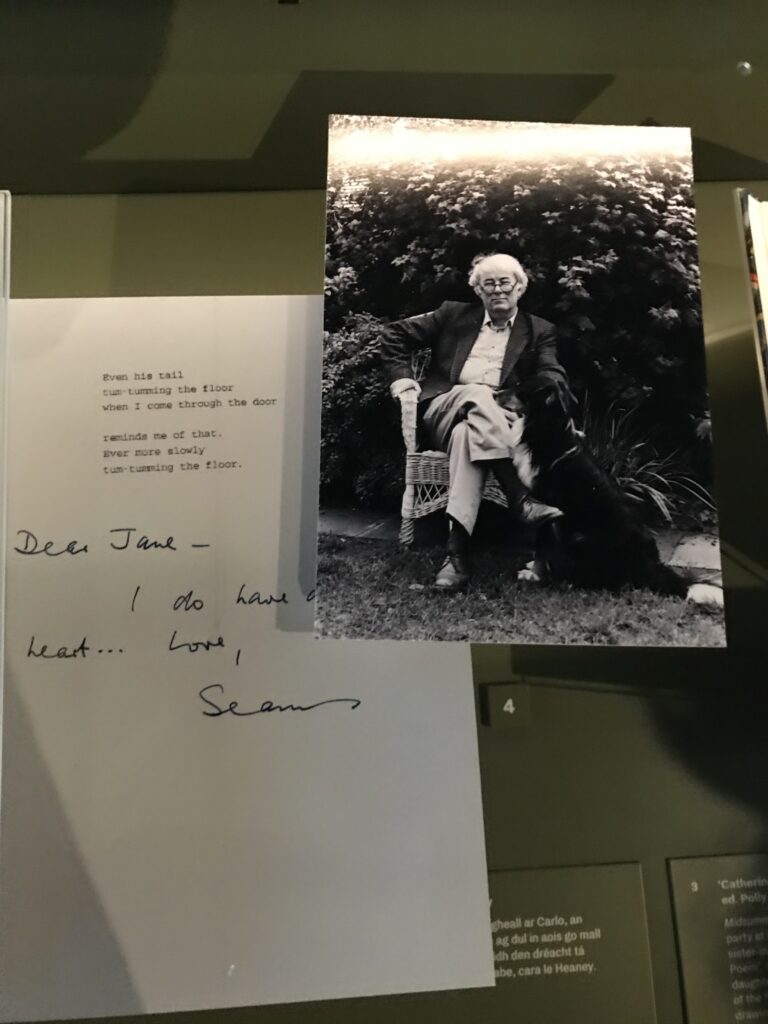

It’s the man who speaks to Ann-Marie the most—the husband, father, friend and companion we come to know through his small personal belongings, photographs and letters—as if you’re looking through the drawers of his desk.

We speak of the things that we gravitated towards first; I mention a picture of Heaney with his dog, and coincidentally Ann-Marie talks about the letter adjacent to it—but we’re both making the same point: it’s the small things.

Nature

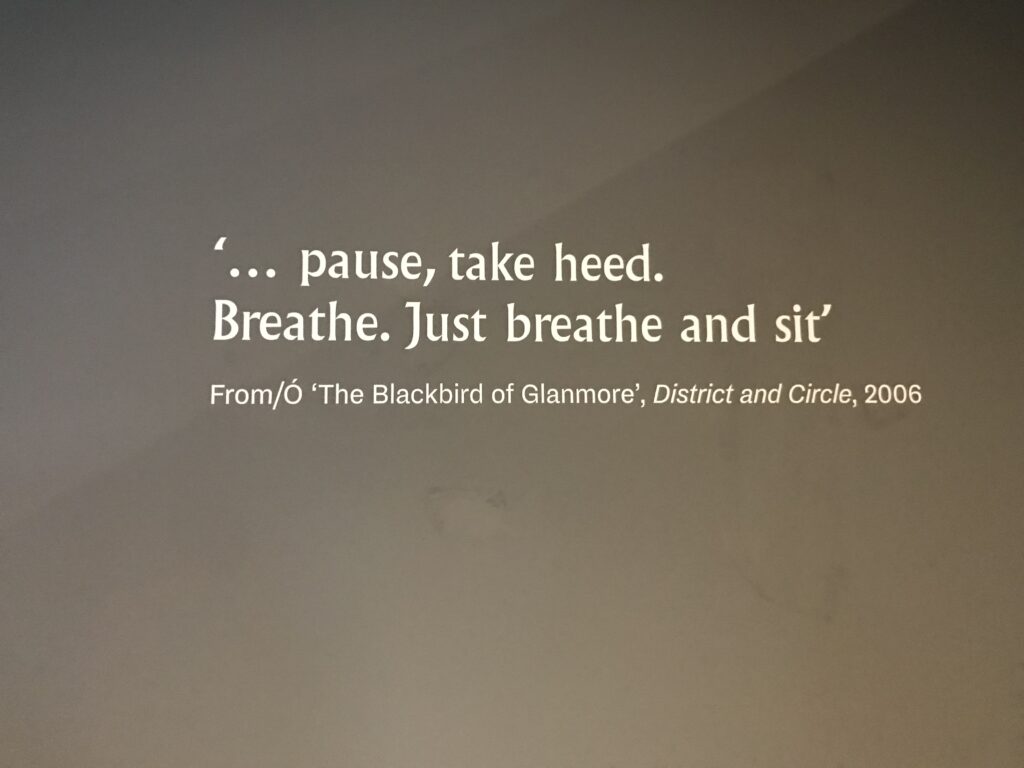

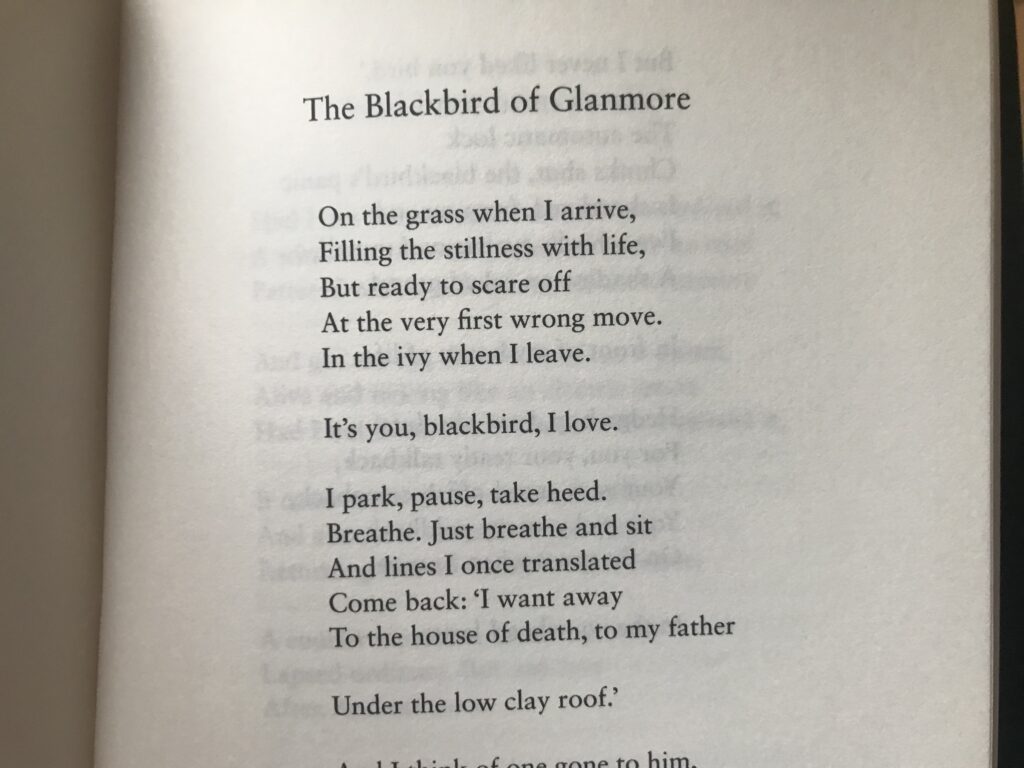

Everyone is drawn to a different side of Heaney, although of course they aren’t really separate; for me it’s not those poems where history and justice rhyme but rather those that have a kind of immanence in nature.

It’s what everyone probably remembers first about Heaney, his words about picking blackberries, his father digging spuds, the bodies in the bog, birdsong, poems which deal as easily with a Greek myth or a sparrow.

It’s hard to explain how Heaney’s poems of the land, ones we all know from school, the bog, bird, moss and water of them—how they seem so utterly different now, heard with a sense of loss, of sadness and fear for the future of our children and our relationship with nature, something which seemed so intractable, so solid, reading those poems as a girl.

This is what pricks the tears at the end, that damn blackbird.

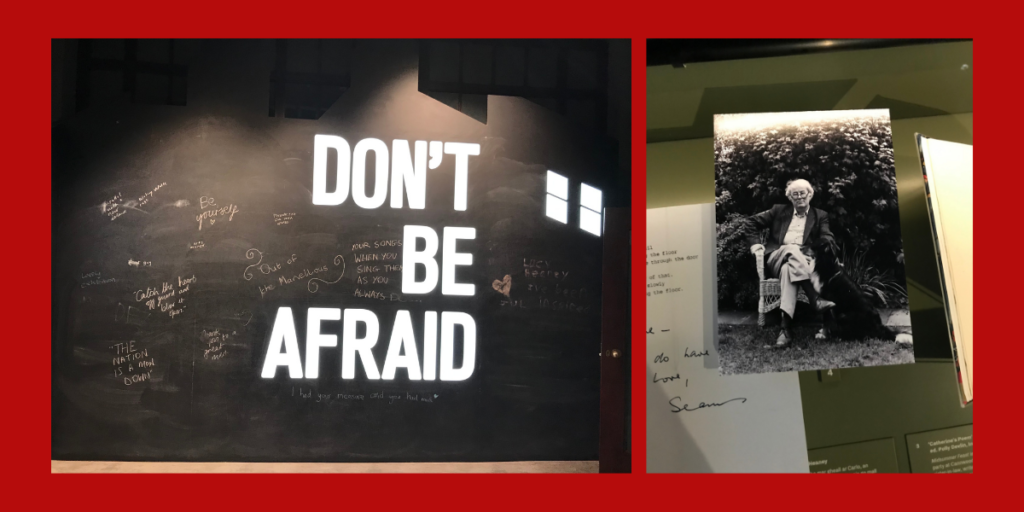

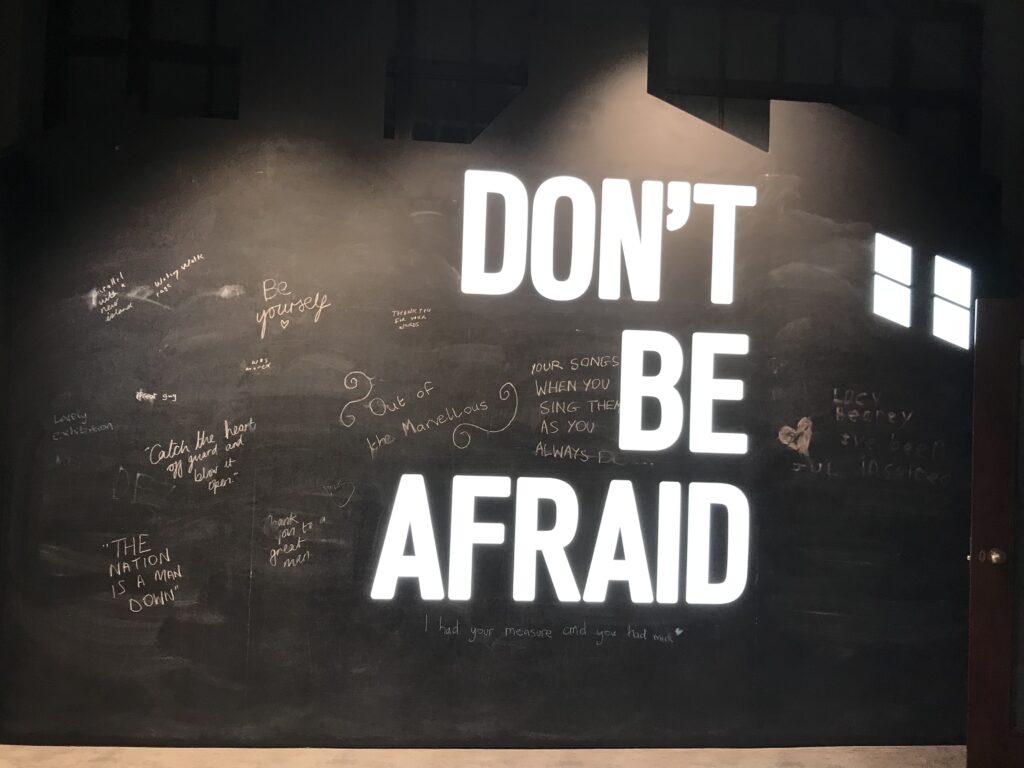

When you leave the exhibition you walk towards a blackboard with Heaney’s last words to his wife Marie: Noli Timere.

Before Covid, people chalked their own messages of love and appreciation from all over the world. I read the words afresh; they mean something different now.

Listen Now Again

We walk down the stairs to the foyer and Ann-Marie gifts me a collection of the gorgeous volume by Faber, Seamus Heaney, 100 Poems.

Looking up before I leave I see the paper sculpture that I’d noticed coming in but hadn’t given my full attention. It has colourful, folded pieces of paper which gradually open up into birds, spiralling upwards towards the ceiling.

I’m thinking about how one life touched—touches—so much else.

“I called myself Incertus, uncertain, a shy soul fretting and all that,” writes Heaney but there is nothing uncertain about the humanity and beauty of this space. As Robert Frost puts it: “a poem begins as a lump in the throat, a homesickness, a lovesickness. It finds the thought and the thought finds the words.”

I feel stranded in the noise outside, coming away from the warmth of Ann-Marie’s conversation, and the intensity of the exhibition. I make my way down Westmoreland Street in the direction of a warm pub.

I message my writer friends something about Heaney’s words, about writing being ‘a revelation of the self to the self’, and then, more accurately, I’m just out of that Heaney exhibition—I’m a bit shook.

You can visit Seamus Heaney: Listen Now Again, a free exhibition by the National Library of Ireland at the Bank of Ireland Cultural and Heritage Centre, Westmoreland Street, Dublin. Open Tuesday to Saturday, 10am to 4pm. Last admission is 3.30pm. More info: http://ow.ly/MWIx50FWdOk