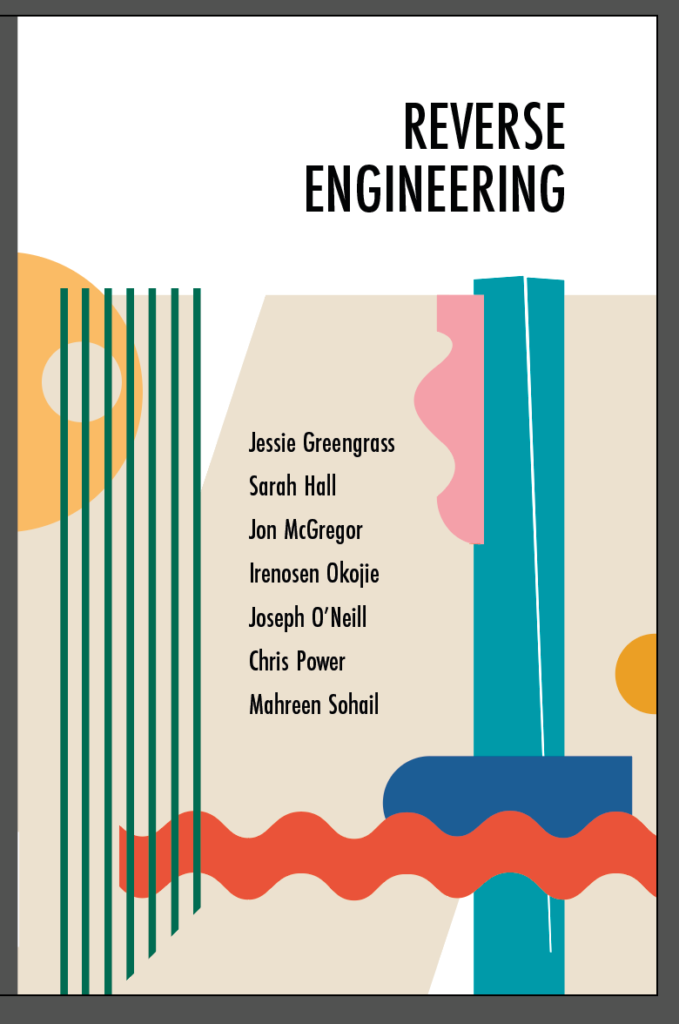

Reverse Engineering|Scratch Books, 2022|ISBN:978-1739830106|£9.99

—Eoghan Smith on Reverse Engineering (Scratch Books), a collection of short stories followed by interviews on craft with their authors

“…a highly useful resource for both aspiring (and established) writers and teachers of creative writing.”

by Eoghan Smith

Reverse Engineering is an anthology of seven stories by seven contemporary short story writers. The impressive line-up includes Jessie Greengrass, Sarah Hall, Jon McGregor, Irenosen Okojie, Joseph O’Neill, Chris Power, and Mahreen Sohail.

Each story is then followed by a discussion between the author and Tom Conaghan, the book’s editor, about the process of writing. These discussions, ranging over many different aspects of the germination of the stories, are the essential element of the collection.

Challenges

Because the stories vary greatly in terms of style, theme and genre, such an enterprise is not without its challenges, however. How, for instance, should the compiler decide which writers to include, and then which stories by those writers should be included?

For writers, there is the jeopardy of having what should effectively be finished works unravelled and their hidden parts exposed.

And of course, it is not long before we necessarily start to stray onto unreliable ground, for we have to rely not only on the veracity of the writer’s memory but also on the distancing perspective, including degrees of pride, embarrassment and regret, that hindsight brings.

Missed opportunity

The opportunity to explain the decisions about the collection’s composition is missed in the editor’s introduction, which instead glosses some established commentary by canonical practitioners of the short story form, such as Poe, Chekov, Carver and Munroe.

We are told that the only criteria by which short stories can be judged is that ‘while there are hundreds of different ways a novel might succeed or fail, a story just has to be brilliant’ (7).

This is a pretty dubious statement, frankly. ‘Brilliant’ is what might be called a non-descriptive adjective – it doesn’t really tell us anything at all – and there are any number of ways a short story too might succeed or fail. Thankfully, the focus of the book is not on what makes a short story ‘brilliant’, but on the processes through which individual stories came into being.

Outstanding work

There are outstanding pieces of work included here, such as Sarah Hall’s magical ‘Mrs Fox’, the winner of the BBC’s 2013 National Short Story Award, and the surprising, surrealist ‘Filamo’ by Irenonen Okojie.

In retrospect, both of these writers consider their stories successful: for Hall, her story achieves what she had hoped for (it does, and more), while Okojie states that she is ‘proud’ of her story (as she should be).

The First Punch

In their promotion of the book, Scratch make the claim that these are ‘seven of the greatest modern short stories’. This is probably not a statement with which Jon McGregor, or indeed many readers of short stories, would agree.

His story ‘The First Punch’, which centres on an aborted affair, is highly unlikely to be regarded as among the best short stories published in the last twenty years.

One can sense McGregor’s unhappiness with the clumsier elements of the story, pointing out that there is much that could be improved about it, such as the syntax, the use of punctuation, the depiction of class, the narrative voice, the dialogue, and so on.

For McGregor, the story appears to be unfinished: ‘the weakness of this story is the work that hasn’t been done yet’ (85).

Honest appraisal

Perhaps McGregor is being a little harsh on himself; ‘The First Punch’ is still a passably good story. Yet, in many respects, McGregor’s self-analysis of the failures within his own story is probably the most interesting contribution to Reverse Engineering, for here is a highly accomplished writer who offers a genuinely honest appraisal of his own work and finds it lacking.

For this he wins the admiration of the reader and a respect for his commitment to the craft of writing.

One senses also the ambivalence of Jessie Greengrass towards her story ‘Theophrastus and the Dancing Plague’, which was included in her 2016 award-winning collection An Account of the Decline of the Great Auk (for Greengrass, the writing is ‘ok’) (124).

Fascinating discussions

Through these discussions we learn that these writers constantly strive for improvement, which is highly edifying.

Elsewhere, there are fascinating discussions about the necessity of editing, of re-writing, of decision-making, of honing technique, and significantly, discovering the voice that will carry the story.

For Greengrass, the voice is something you feel: ‘it’s like being able to just hear that a piece of music is in tune’ (120). For Mahreen Sohail in ‘Hair’, on the other hand, the voice was a more conscious decision: ‘the voice came from the first line. I knew I didn’t want a first person or a named third person narrator’ (104).

One learns, if it needed to be learned, that there is no single method for writing a short story and that each writer has their own process.

Yet, what does remain consistent throughout is that every story requires work: writing is not alchemy. It is a concerted process of creative effort, gradual discovery, continual refinement, and the exercising of the good judgement that comes with repetition and practice.

Useful resource

Chris Power’s substantial responses to the questions about his tense story ‘The Crossing’ make particularly good reading. From him we learn that writing is a craft that requires ruthless de-junking, revision, recognizing the importance of detail and much more besides.

In this regard, Reverse Engineering would be a highly useful resource for both aspiring (and established) writers and teachers of creative writing.

Joseph O’Neill

Power, like most of the contributors, is expansive in his replies. I say most, because one could not say the same for Joseph O’Neill’s responses, some of which are shorter than the questions.

The only truly valuable thing the reader learns about O’Neill’s excellent ‘The Flier’, which is judiciously placed at the end of Reverse Engineering, is that he is either not particularly illuminating about his own writing or was reticent to re-examine it in any great detail.

Perhaps, to be generous, we can say that O’Neill considers ignorance and discovery as integral to successful story writing.

On his protagonist: ‘I don’t know what to think of him’. On the climax of the story: ‘I didn’t see it coming’. On the recurrence of theme: ‘I wasn’t aware of it until you asked me. That’s great. The story should know something that you, the writer, don’t know’.

Much to ponder

Who knows what this mysterious last statement means. Indeed, his answers are so poor that the book ends on a flat, disappointing note, and the reader might well have been better served if a writer had been found to engage more constructively with the project.

This aside, Reverse Engineering provides us with much to enjoy and to ponder about the contemporary short story, particularly for those of us hungry to learn the secrets of this beautiful artform.

Eoghan Smith is the author of The Failing Heart (Dedalus 2018). His second novel, A Provincial Death is out now with Dedalus.